A series of mysterious deaths followed the 1922 opening of King Tutankhamun’s tomb, sparking the legend of the ‘Pharaoh’s curse.’ Scientist Ross Fellowes has recently put forward a biological explanation for these deaths, challenging the notion of a supernatural curse. According to Fellowes, radiation poisoning resulting from natural elements like uranium and intentionally deposited toxic waste within the sealed vault is the likely cause.

The study indicates that exposure to these substances could have led to various cancers, such as the one that claimed the life of archaeologist Howard Carter, the first to enter Tut’s tomb. Notably, Carter succumbed to Hodgkin’s lymphoma, a cancer associated with radiation poisoning. Similarly, Lord Carnarvon, who also entered the tomb, died from blood poisoning, possibly exacerbated by a mosquito bite.

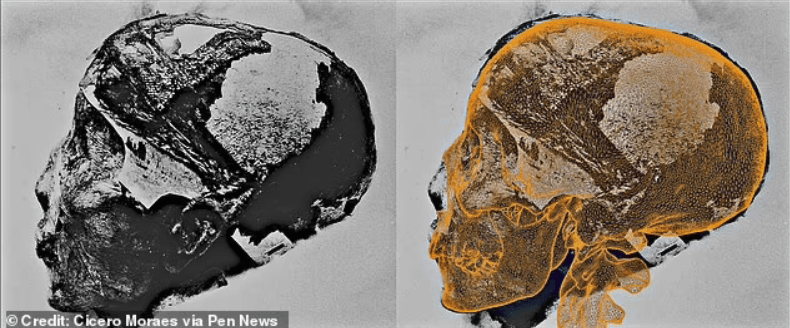

Moreover, inscriptions in other Egyptian burials warned of ‘evil spirits’ in forbidden areas, suggesting ancient awareness of toxins. High radiation levels documented in Old Kingdom tomb ruins support the theory, particularly in stone coffers made of basalt, which emitted intense radiation. Studies also found elevated radon gas levels in various tomb locations, further implicating unnatural sources.

‘Reported strong radiation (as radon) in tomb ruins has been loosely attributed to the natural background from the parent bedrock,’ Fellowes shared.

‘However, the levels are unusually high and localized, which is not consistent with the characteristics of the limestone bedrock but implies some other unnatural source(s).’

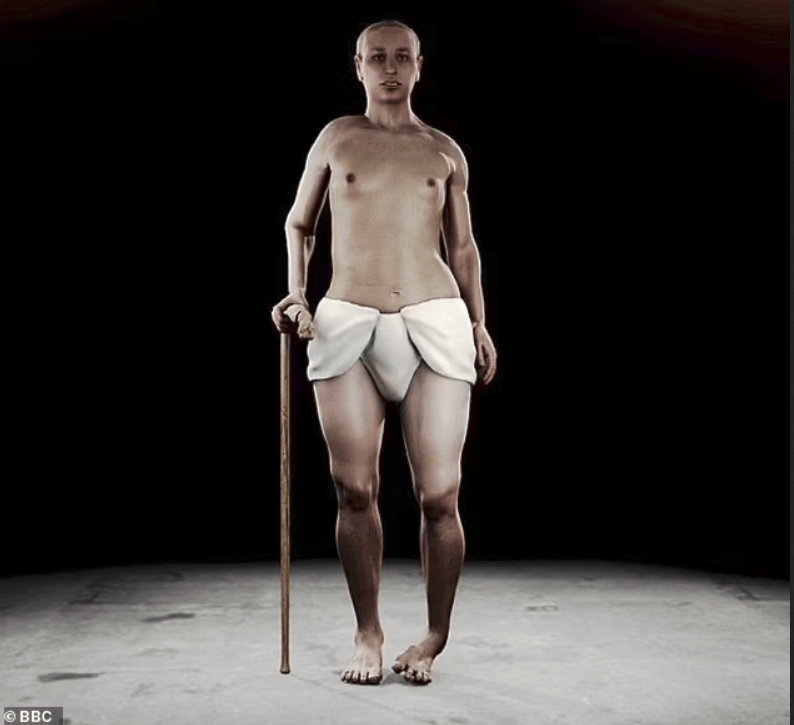

Tutankhamun’s tomb unveiling showcased a grand burial chamber brimming with riches, underscoring his position as an Egyptian pharaoh during the 18th dynasty. His rule was characterized by a marriage to his half-sister and probable health challenges arising from his parents’ incestuous union. Recent investigations indicate Tut endured physical limitations like buck teeth, girlish hips and a club foot, potentially constraining his movements.

Contrary to earlier speculation of murder or chariot crashes, genetic analysis and evidence of numerous walking canes in Tut’s tomb suggest he likely died of an inherited illness exacerbated by his physical limitations. This aligns with the theory that Tut’s family history, characterized by incestuous relationships, contributed to hormonal imbalances and premature death.

Fellowes’ study offers a fresh perspective on one of ancient Egypt’s enduring mysteries by debunking the supernatural aspects of the ‘Pharaoh’s curse’ and providing a scientific explanation for the deaths linked to Tut’s tomb. Through a thorough examination of Tut’s remains, previous myths about his death are challenged, shedding light on his life and circumstances.

The study is published in the Journal of Scientific Exploration.