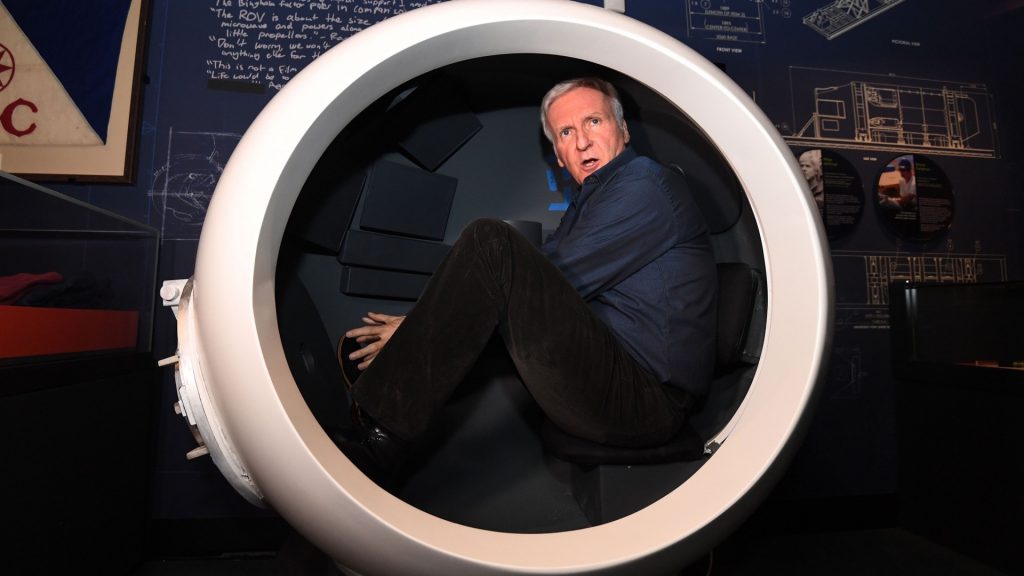

James Cameron, the renowned director of Titanic and Avatar, has stirred controversy with his strong support for deep-sea mining, a practice involving the extraction of valuable materials from depths beyond 200 meters of seawater. Having completed over 75 deep-sea dives, Cameron stands firmly behind his belief that deep-sea mining is safer than common activities like riding an elevator or boarding an airplane.

This assertion comes at a time when deep-sea mining is a topic of concern among nations and global regulatory bodies. The International Seabed Authority (ISA) recently convened in Jamaica to discuss and establish rules for the activity. In a significant victory for environmentalists, the ISA rejected industrial-scale mining after careful deliberation. Cameron’s endorsement of deep-sea exploration as a safer venture than everyday activities may raise eyebrows, but it reflects his extensive experience and understanding of the deep ocean.

James Cameron’s travels have brought him to some of the most inaccessible and uncharted areas of the world, such as the Challenger Deep, which is located more than 10,000 meters beneath the surface of the ocean. He now has a distinctive viewpoint on deep-sea mining as a result of his missions. Cameron notes that although the bottom is home to an array of fascinating and different species, large areas are barren and primarily made of clay. Deep-sea mining firms are drawn to areas like the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) in the Pacific Ocean, which is rich in polymetallic nodules.

Scientists recently made an astounding discovery in the CCZ, identifying 5,000 new species in May. These newfound species face the threat of extinction if mining operations proceed. Nevertheless, the ISA has established Areas of Particular Environmental Interest (APEIs) to safeguard certain regions from mining activities, prioritizing the protection of biodiversity and habitats.

Cameron’s defense of deep-sea mining is clear: society focuses too much on some things and neglects others. Mining in highly sensitive ecosystems is significantly dissimilar from mining the abyssal seafloor, yet conservationists are still concerned with the long-term impacts it could have on vulnerable habitats.

Cameron’s travels into the deep waters of the ocean have been fruitful, introducing us to new species like sea cucumbers and squid worms. His knowledge and enthusiasm for what lies beneath the surface make him a pioneer in responsible deep-sea mining that preserves delicate marine environments.

The dispute around deep-sea mining is still going strong. Achieving a compromise between taking advantage of resources and keeping our oceans safe will surely need assistance from all over the world, as well as attentive thought to the effects on our much-cherished maritime habitats.