A quiet revolution is unfolding across China’s factory floors, one that has left Western executives “humbled,” “shaken,” and in some cases, downright alarmed. From driverless car assembly lines to fully automated “dark factories”, China’s manufacturing transformation has reached a point where machines, not people, build the future.

As Ford CEO Jim Farley put it after touring a string of Chinese car plants, “It’s the most humbling thing I’ve ever seen”, as reported by The Telegraph. His words echo the growing realization among global industry leaders that China’s rapid automation and engineering prowess may have already tipped the scales in global manufacturing.

Farley’s visit to China left him in awe of the technical sophistication and efficiency now defining Chinese-built vehicles. “Their cost and the quality of their vehicles is far superior to what I see in the West,” he admitted in July, warning that “if we lose this, we do not have a future at Ford.”

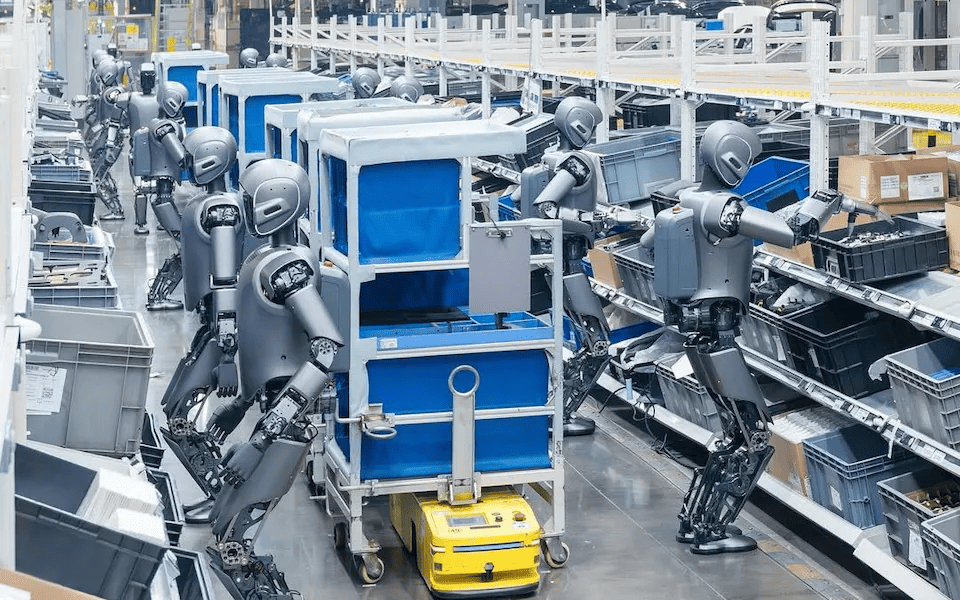

He’s not alone. Andrew Forrest, the billionaire founder of mining and energy giant Fortescue, came away from Chinese factories equally astonished. “I can take you to factories where machines come out of the floor and begin to assemble parts,” Forrest described. “After about 800 or 900 meters, a truck drives out. There are no people, everything is robotic.”

Similarly, Greg Jackson, CEO of Octopus Energy, recalled visiting a “dark factory” producing an “astronomical number of mobile phones” where the lights remained off because no workers were needed. “China’s competitiveness has gone from low wages to a tremendous number of highly skilled, educated engineers who are innovating like mad,” Jackson observed.

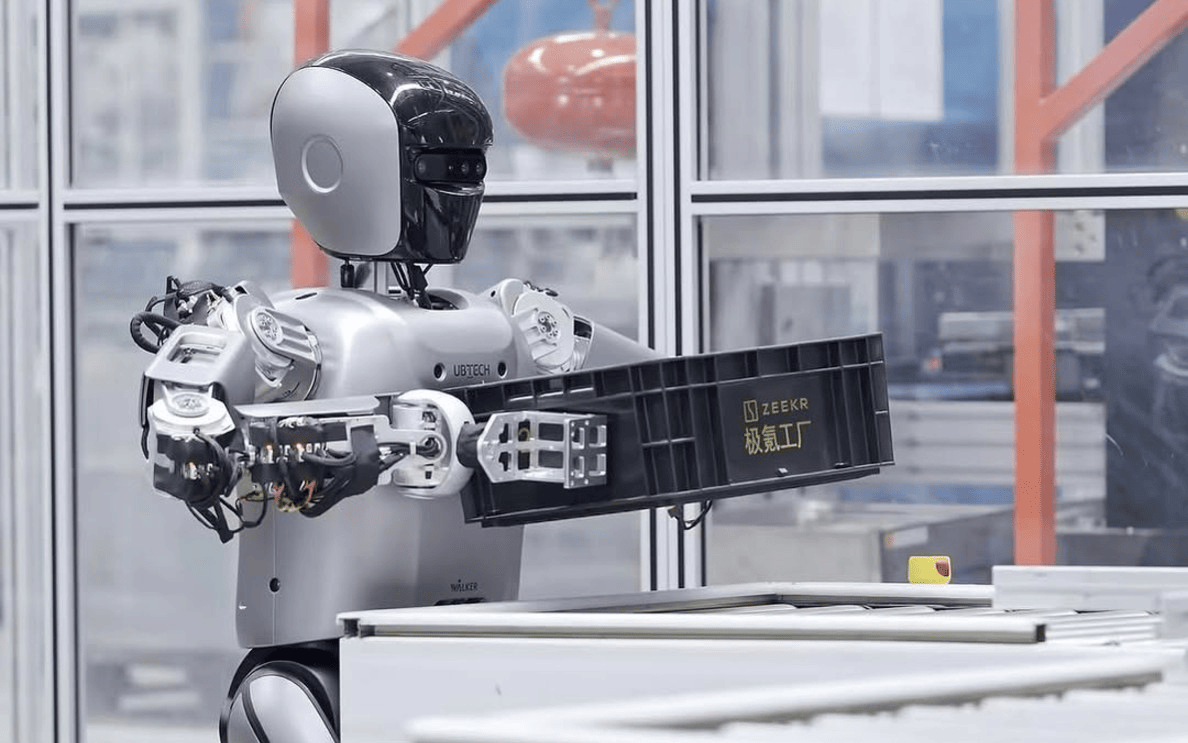

Once known for churning out low-cost goods, China has refashioned itself as the world’s automation powerhouse. Backed by government incentives, tax rebates, and state-led industrial policy, Beijing has poured vast resources into robotics, AI, and high-value manufacturing.

Figures from the International Federation of Robotics (IFR) show that between 2014 and 2024, the number of industrial robots in China exploded from 189,000 to over two million. In 2024 alone, Chinese factories added 295,000 new robots dwarfing Germany’s 27,000, the US’s 34,000, and the UK’s 2,500.

China now leads the world in robot density, with 567 robots per 10,000 workers, far ahead of Germany (449), the US (307), and the UK (104). This rapid automation has bolstered productivity, strengthened supply chain dominance, and given China a potential strategic edge in both economic and military terms.

Experts argue that China’s automation drive isn’t only about efficiency it’s also about demographic survival. With a rapidly ageing population and fewer workers entering the labor force, Beijing’s “jiqi huanren” policy literally, “replacing humans with machines” seeks to sustain output even as labor shortages loom.

As Rian Whitton of Bismarck Analysis explains, “They want to automate not because they expect higher margins, but to compensate for population decline and gain a competitive advantage.”

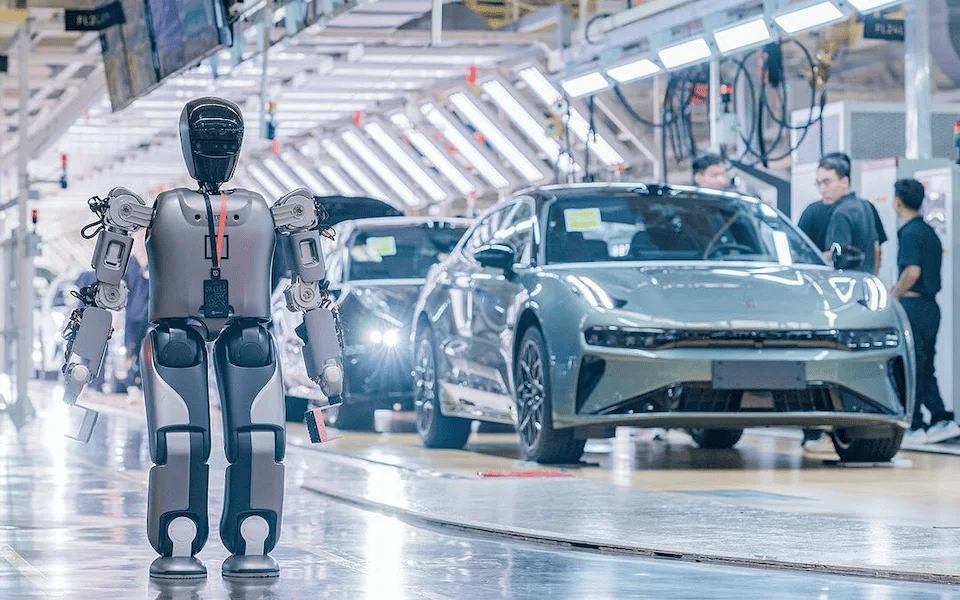

For Western automakers, the challenge is already visible on the roads. Chinese electric vehicle brands such as BYD are rapidly outpacing traditional names. In the UK, BYD’s September sales grew tenfold, surpassing legacy brands like Mini, Renault, and Land Rover.

Far from the “cheap knock-offs” once mocked on Top Gear, modern Chinese cars now rival European models in design, software, and price competitiveness. As Mike Hawes, head of the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT), notes, “They can develop and execute models in probably half of the time most European car makers can.”

Economists like Sander Tordoir of the Centre for European Reform warn that Europe must accelerate its own robotics deployment to keep up. “If China is extremely good at it, then we should try to catch up,” he argues. “Robotics, if deployed well, can lift the productivity of your economy greatly.”

Despite these warnings, Britain remains near the back of the automation pack. The country added just a few thousand robots last year, with installations actually falling by 35%.

Whitton argues that instead of pouring billions into speculative “green hydrogen” projects, the UK should invest in industrial robotics to reignite productivity. “Why not five billion a year in grants for capital equipment?” he suggests. “That would arguably get a bigger bang for our buck.”

Ironically, countries that embraced automation during the first “China shock” of the 2000s managed to retain more manufacturing jobs. As Whitton concludes, “People talk a lot about how automation will lead to job losses. But actually, the job losses are going to be disproportionately in the countries that don’t automate.”