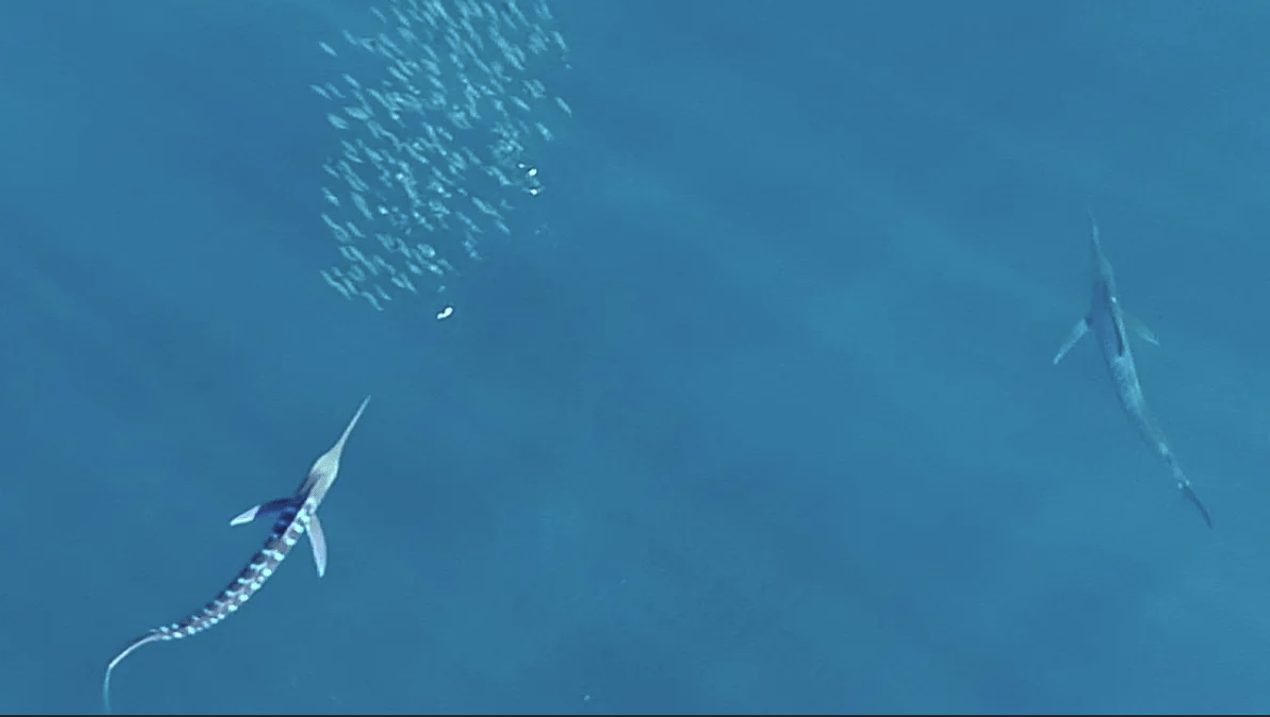

Marlin and sailfish, which are some of the top hunters in the ocean and known for being super fast, have been seen working together in groups to catch prey like sardines. Scientists, using really advanced drones, have found something fascinating about how they hunt: they use colors to talk to each other while hunting.

The striped marlin, known scientifically as Kajikia audax, exhibits color changes in its stripes as a prelude to launching attacks on prey. Through drone footage analysis, researchers discovered that the marlin become significantly brighter in their striped patterns just before executing a strike, returning to their original coloration post-attack. This phenomenon, previously undocumented in group-hunting predators, serves as a crucial signal within the hunting group.

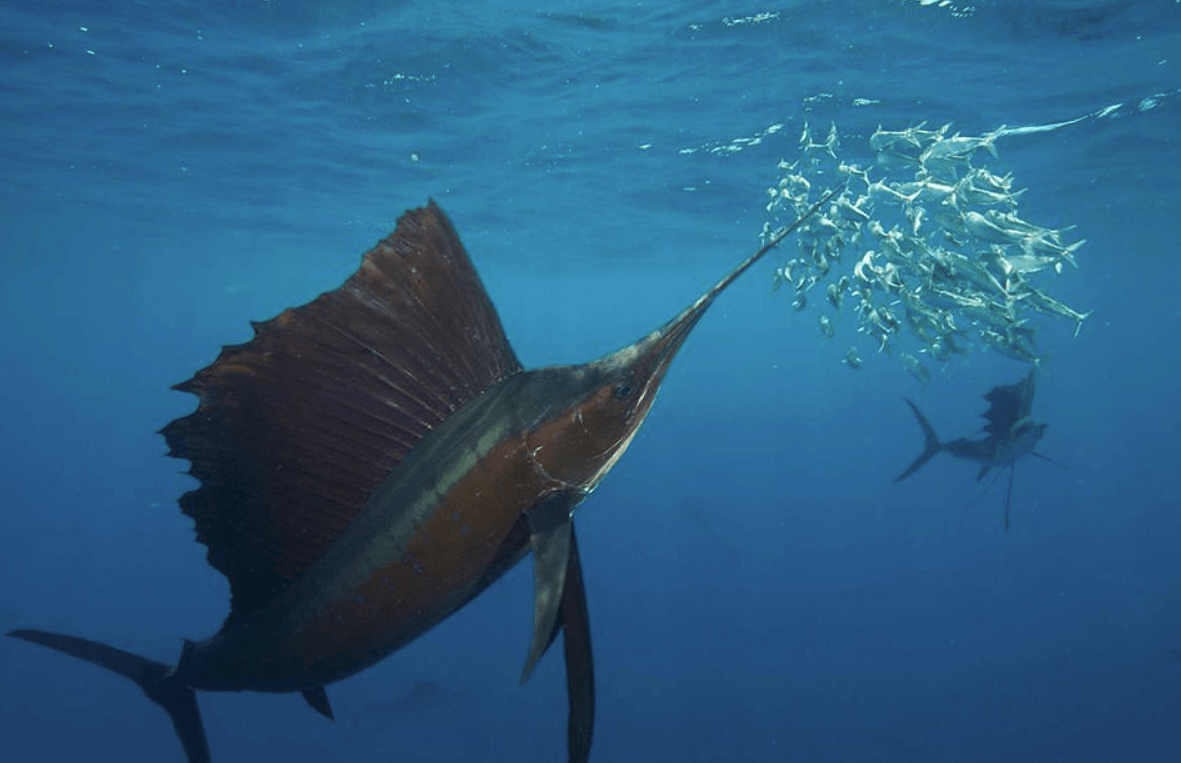

These marlins possess elongated rostrums or snouts, which they employ to stun and capture prey. However, in the densely populated waters of the Pacific and Indian Oceans, such strikes could inadvertently harm fellow hunters. With lengths reaching up to 4 meters (14 feet) and weights ranging from 113 to 204 kilograms (250-450 pounds), marlins are formidable predators.

Alicia Burns of Humboldt University in Berlin, Germany, highlights the significance of this discovery, emphasizing that the color change acts as a warning signal to fellow marlins, preventing them from inadvertently attacking during a coordinated hunt. Similar mechanisms are observed in other species like the medaka fish, where color changes precede aggressive behavior.

“We documented for the first time rapid color change in a group-hunting predator, the striped marlin, as groups of marlin hunted schools of sardines,” says Alicia.

The researchers’ analysis, based on 12 video clips capturing marlin hunting Pacific sardines, elucidated the distinct color alterations during the hunting sequence.

“We found that the attacking marlin ‘lit up’ and became much brighter than its groupmates as it made its attack before rapidly returning to its ‘non-bright’ coloration after its attack ended,” continued Burns.

This breakthrough opens avenues for further investigation into the intricacies of marlin behavior. Future research aims to explore whether solitary marlins exhibit similar color changes during hunting and if this signaling mechanism extends beyond group hunting contexts.

“Color change in predators is rare, but especially so in group-hunting predators,” Burns said. “Although it is known that marlin can change color, this is the first time it’s been linked to hunting or any social behavior.”

Understanding these dynamics contributes not only to our comprehension of marlin behavior but also sheds light on broader ecological interactions within marine ecosystems. By unraveling the nuances of predator-prey relationships and social behaviors, researchers pave the way for more comprehensive conservation strategies aimed at preserving marine biodiversity.