Researchers at the University of Southern California Alfred E. Mann Department of Biomedical Engineering have developed a “heart attack on a chip,” a device that could one day serve as a testbed to develop new heart drugs and even personalized medicines.

“Our device replicates some key features of a heart attack in a relatively simple and easy-to-use system,” said Megan McCain, an associate professor of biomedical engineering and stem cell biology and regenerative medicine who developed the device with postdoctoral researcher Megan Rexius-Hall.

Coronary heart disease is America’s No. 1 killer. In 2018, 360,900 Americans succumbed to it, making heart disease responsible for 12.6% of all deaths in the United States, according to the AHA. Severe coronary heart disease can cause a heart attack, which accounts for much of that pain and suffering.

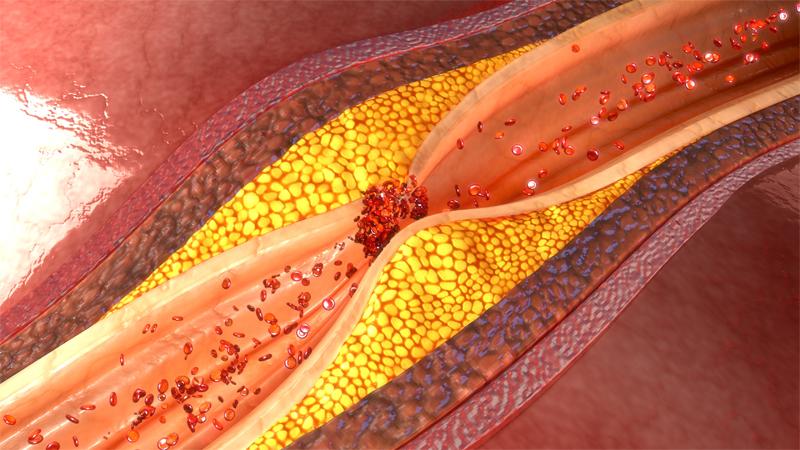

Heart attacks occur when fat, cholesterol and other substances in the coronary arteries severely reduce the flow of oxygen-rich blood to part of the heart. Between 2005 and 2014, an average of 805,000 Americans per year had heart attacks.

Even if a patient survives a heart attack, over time they can become increasingly fatigued, enervated, and sick; some even die of heart failure. That’s because heart cells don’t regenerate like other muscle cells. Instead, immune cells appear at the site of injury, some of which can be harmful. Additionally, scarring develops that weakens the heart and the amount of blood it can pump.

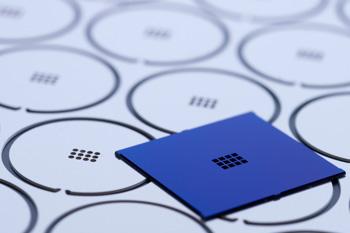

The heart attack on a chip is designed from the ground up. At the base is a 22-millimeter-by-22-millimeter square microfluidic device slightly larger than a quarter—made from a rubber-like polymer called PDMS—with two channels on opposing sides through which gases flow. Above that sits a very thin layer of the same rubber material, which is permeable to oxygen. A microlayer of protein is then patterned on the top of the chip “so that the heart cells align and form the same architecture that we have in our hearts,” McCain said. Finally, rodent heart cells are grown atop the protein.

To mimic a heart attack, gases with and without oxygen are released through each channel of the microfluidic device, “exposing our heart on a chip to an oxygen gradient, similar to what happens in a heart attack,” McCain said.