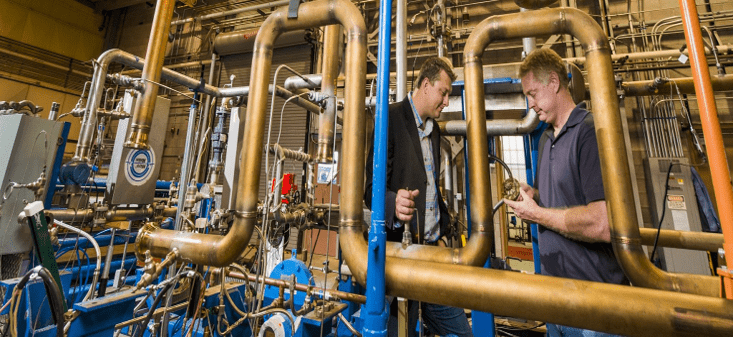

Sandia National Laboratories has generated electricity using heated supercritical carbon dioxide instead of steam. The organization achieved this feat at the Sandia-Kirtland Air Force Base electrical grid, according to the press release.

Superficial carbon dioxide is a stable material that behaves like a liquid and a gas, and it does so because it is under so much pressure. Moreover, it remains within the chamber and is not released as a greenhouse gas, making it immensely hotter than steam (1,290 degrees Fahrenheit or 700 Celsius).

“We’ve been striving to get here for several years, and to be able to demonstrate that we can connect our system through a commercial device to the grid is the first bridge to more efficient electricity generation,” said Rodney Keith, manager for the advanced concepts group working on the technology.

“Maybe it’s just a pontoon bridge, but it’s definitely a bridge. It may not sound super significant, but it was quite a path to get here. Now that we can get across the river, we can get a lot more going.”

On April 12, the first 10 kilowatts of energy were generated. It may not be much, but it was a significant advancement. Unfortunately, this happened only after the Sandia National Laboratories managed to heat their superficial CO2 to 600 degrees.

“We successfully started our turbine-alternator-compressor in a simple supercritical CO2 Brayton cycle three times and had three controlled shutdowns. After that, we injected power into the Sandia-Kirtland grid steadily for 50 minutes,” said Darryn Fleming, the lead researcher on the project.

“The most important thing about this test is that we got Sandia to agree to take power. It took us a long time to get the data needed to let us connect to the grid. Any person who controls an electrical grid is very cautious about what you sync to their grid because you could disrupt the grid. You can operate these systems all day long and dump the power into load banks, but putting even a little power on the grid is an important step.”

Following this successful test, the team is now modifying the systems so that they may be able to operate at higher temperatures, 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit and above. Could this be the future of electricity?