Archaeologists are sometimes referred to as “stumped” or “baffled” by their findings. Experts frequently understand the meanings behind the majority of ancient artifacts. Still, there are a few exceptions. Here, we examine a few of the most fascinating artefacts that have been found so far.

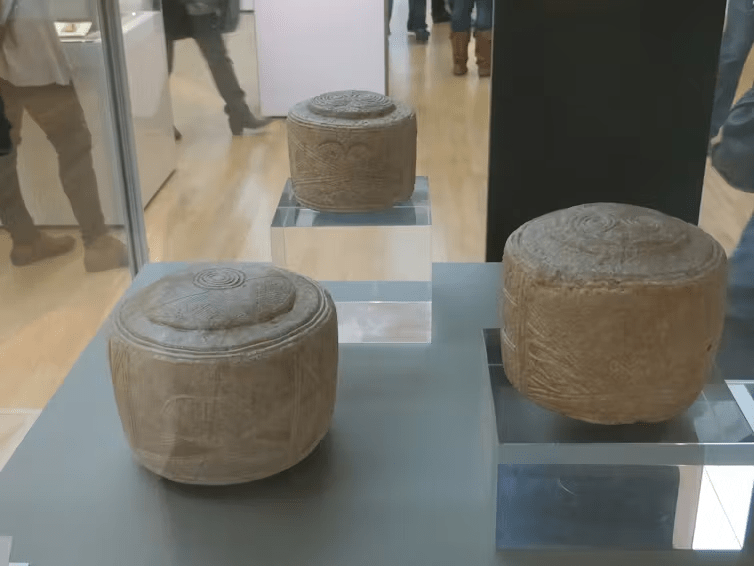

A prominent example of these mysterious objects are the engraved stone balls discovered in Scotland, which belong to the later Neolithic era (about 3200–2500 BCE). Over 425 of these balls, usually the size of a cricket ball, are made of different stones. Their carved surfaces have deep incisions that define knobs and lobes, elevated circular discs, and ornamentation-like spirals and concentric circles that resemble the patterns on massive stones and modern pottery.

These stone balls, found in towns and burials, are rarely similar, and the majority of them are found alone, indicating that they were not a set. Since their discovery in the 19th century, there has been discussion regarding their initial use. Theoretical objects include ball bearings for moving megaliths, mnemonic devices, measuring weights, weaponry, and even holders for yarn. There has been much guesswork, but their precise function is still a mystery.

Another strange artifact is the Roman dodecahedra, which dates to the Roman era in Britain (43–410 CE). Roughly 130 of them are scattered throughout the former Roman Empire’s northwest regions. These exquisitely made copper alloy artifacts exhibit little signs of use wear and are not found in ancient art or literature. Archaeologists are still unsure about their actual purpose despite several theories, such as the one that suggests they were used for knitting gloves.

Three carved chalk cylinders, or the Folkton Chalk Drums, were found in a child’s grave at Folkton, North Yorkshire 1889. A fourth, undecorated drum was discovered in West Sussex in 1993; it was decorated with geometric patterns and facial features; in 2015, an extremely elaborate example was recovered in East Yorkshire. Despite their name, it seems unlikely that these chalk drums were ever used for musical purposes. Some academics speculate that the circumferences of these objects may be related to the “long foot,” a standard measure; others imply ties with astronomical observations. Their placement in children’s graves implies a more considerate or symbolic purpose.

Prominent for its remarkable goldsmithing, the Bronze Age produced tiny penannular rings that may be found in Ireland, Britain, and some regions of France. Despite their beautiful geometric engravings and frequent pair finds, their purpose has been questioned. Nose rings, earrings, and hair ornaments are other suggestions, although these explanations fall short due to their design components. These mysterious rings might have some meaning thanks to the discovery of facial jewellery in burials recently found in Turkey.

A mystery also surrounds cosmetic grinders, tiny copper alloy kits dating from the late Iron Age to the early Roman era (around 100 BCE to 200 CE). Made up of a “pestle” and a “mortar,” these items frequently have waterbird and bovid ornamental themes; some sets even have phallic symbols. Their purpose as grinding tools is obvious, but what they were used to prepare is unclear. Narcotics, cosmetics, aphrodisiacs, and medicines are among the hypotheses. It is advised that amateur finders put these mortars for professional analysis rather than cleaning them in the hopes of discovering their original contents.