In an age marked by geopolitical uncertainty and technological dangers, the elite has turned to an ancient survival approach: burrowing underground. The modern bunker industry is a market worth $137 million last year and is projected to grow to $175 million by the decade’s end. Yet, experts argue that these elaborate shelters offer little more sense of control than psychological comfort.

The growing bunker culture, fueled by “doomsday preppers” and wealthy patrons, appears more rooted in anxiety than practicality. Alicia Sanders-Zakre from the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons dismisses bunkers as inadequate responses to the catastrophic realities of nuclear war. “Bunkers are not a tool to survive a nuclear war, but a tool to allow a population to endure the possibility of a nuclear war psychologically,” she explained.

Even if one manages to evade immediate destruction, the aftermath remains grim. Radiation, described by Sanders-Zakre as a “uniquely horrific aspect of nuclear weapons,” lingers long after the initial blast, causing intergenerational health crises similar to those observed in the aftermath of Chernobyl. And beyond the fallout lie even starker challenges: starvation, dehydration, and societal collapse. Her conclusion is unequivocal: “The only solution to protect populations from nuclear war is to eliminate nuclear weapons.”

The obsession with bunkers isn’t confined to private initiatives or the United States. Switzerland, a country where every citizen is guaranteed a spot in a government shelter, has committed hundreds of millions of dollars to revamp its Cold War-era facilities. This reflects a broader revival of “bunker culture,” albeit under different political and social contexts.

Back in the U.S., the narrative is increasingly driven by the private sector. Despite their promises, experts like Sam Lair from the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies remain skeptical of their utility. “Even if a nuclear exchange is perhaps more survivable than many people think, I think the aftermath will be uglier than many people think as well,” Lair noted. The societal upheaval following such an event, he suggests, would be profound and wrenching, undermining any illusion of normalcy or safety offered by a bunker.

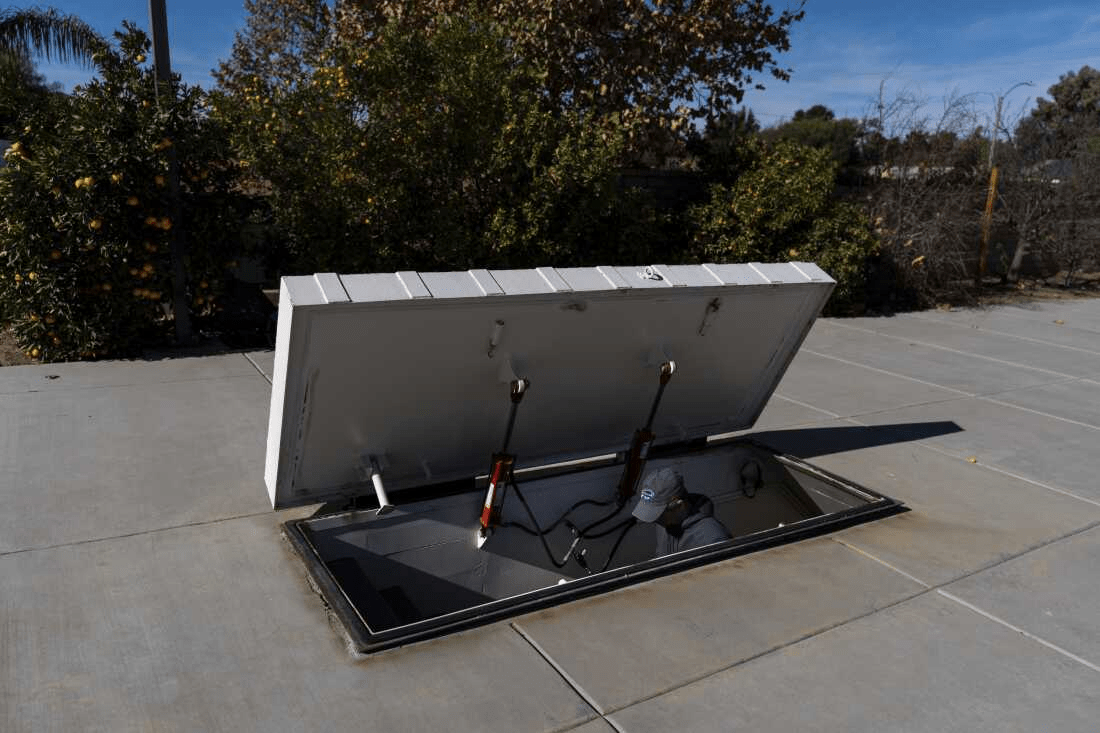

Decades ago, building bomb shelters was a government-endorsed civic duty. Today, the “big business of bunkers” caters to an individualistic, profit-driven ethos. As Lair observed, the political cost of revisiting public shelter programs outweighs their perceived benefit, leaving the industry to thrive on the anxieties of the wealthy.