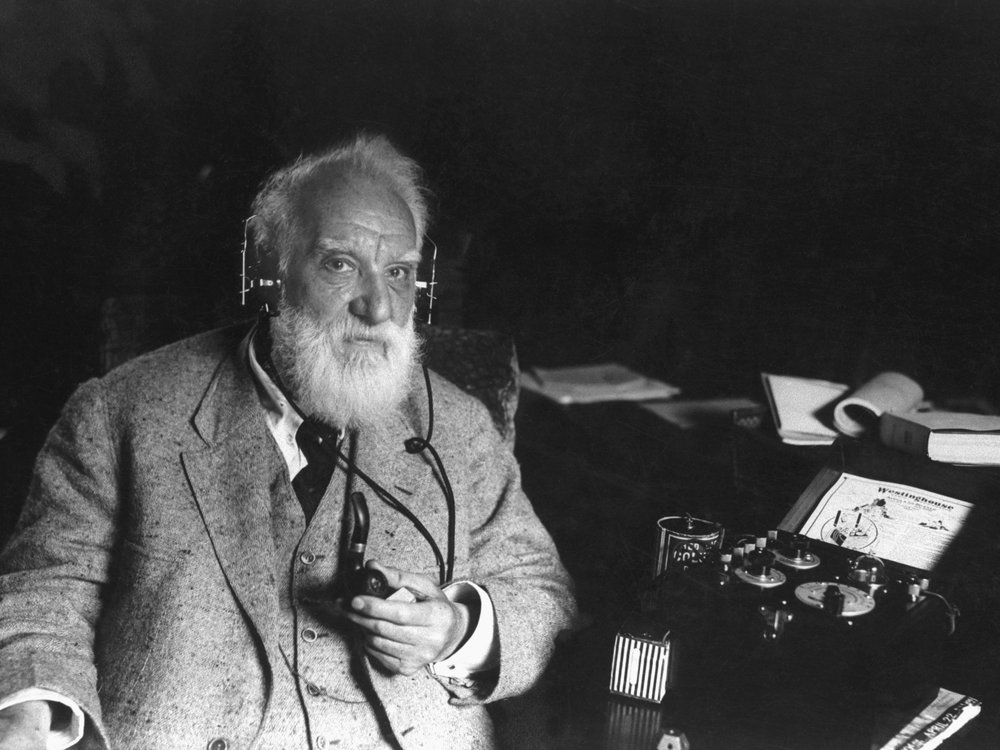

Nobody knew what Alexander Graham Bell sounded like until about ten years ago. In 2013, Smithsonian researchers discovered a previously “unplayable” recording of the scientist on a wax-and-cardboard disc.

“Hear my voice,” Bell stated. The world could finally hear his voice for the first time since his death in 1922.

The new initiative will get underway in the fall.

The Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History has announced a new initiative to restore hundreds of previously unseen sound recordings made by Bell and his colleagues between 1881 and 1892 at Volta Laboratory in Washington, D.C., and Bell’s home in Baddeck, Nova Scotia. They are among the world’s very first sound recordings.

“Over the three-year duration of this remarkable project, ‘Hearing History: Recovering Sound from Alexander Graham Bell’s Experimental Records,’ we will preserve and make accessible for the first time about 300 recordings that have been in the museum’s collections for over a century, unheard by anyone,” says Anthea M. Hartig, the museum’s Elizabeth MacMillan director, in a statement.

Bell, who was born in Scotland in 1847, is best known as the inventor of the telephone. On March 7, 1876, he got a patent for his methods. A few days later, he placed his first phone call to his laboratory assistant, saying, “Mr. Watson, come here. “I’d like to see you.”

Researchers have previously recovered sound from 20 experimental recordings made at Volta Laboratory in recent years, including the sole documented recordings of Bell’s voice. The new effort will concentrate on recovering the remains of the collection.

The cardboard-and-wax discs manufactured by Bell and his colleagues, which the study team will translate, were once regarded as “mute artifacts,” according to Carlene Stephens, curator at the National Museum of American History, in 2013. She started to worry “whether we’d ever know what was on them” because the details of Bell’s attempts to play them back had been lost to history.

However, a new technology for hearing the recordings was devised because of the untiring efforts of experts from the museum, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, and the Library of Congress.

The team uses computers to create a digital scan of the wax disc’s grooves, removing any scratches or other damage that would hinder the recovery effort. The software then uses a virtual stylus to move over the grooves of a virtual record to recreate the audio as a new digital file.

As a result, a sound that had been unreachable for more than a century was made available.