Three tonnes of space debris – the remains of a rocket – are ready to collide with the moon, carving up a gigantic crater and scattering dust across its surface.

Experts estimate the debris will collide with the far side of the moon, away from the prying eyes of observatories, on Friday at a speed of 9,300km/h (5,800mph). It might take weeks, if not months, for satellite photographs to establish the impact.

Experts believe the debris has been drifting recklessly through space since China launched it over a decade ago. However, Chinese officials claim it is not theirs.

Bill Gray, an asteroid tracker in the United States, believes it is China’s rocket.

“I’ve become a little bit more cautious of such matters,” he said. “But I really just don’t see any way it could be anything else.”

Scientists predict that the item will slash a hole 10 to 20 meters (33 to 66 feet) across the moon.

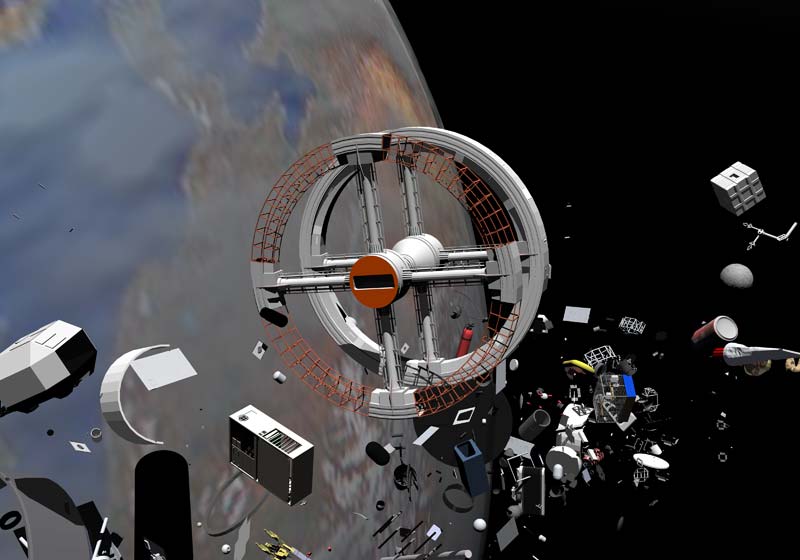

Low-orbiting space debris is quite simple to locate and track. Objects flying farther into space are unlikely to collide with anything, and these far-flung fragments are largely forgotten, except by a few observers who love playing celestial detective on the side.

In January, Gray, a mathematician, and physicist, spotted the crash trajectory, and SpaceX initially blamed the forthcoming lunar junk. A month later, he corrected himself, claiming the “mystery” object was not a SpaceX Falcon rocket upper stage from NASA’s deep space climate observatory mission in 2015.

The US Space Command verified on Tuesday that the Chinese upper stage from the 2014 lunar mission did not de-orbit, as previously stated in its database. However, it was unable to determine the object’s origin.

Gray’s new assessment is supported by Jonathan McDowell of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, but “the effect will be the same.” It will create yet another tiny crater on the moon.”

China has a lunar lander on the moon’s far side, but it will be too far away to detect the collision on Friday. NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter will be out of reach as well. It’s also doubtful that India’s moon-orbiting Chandrayaan-2 would pass by at that time.

“I had been hoping for something [significant] to hit the moon for a long time. Ideally, it would have hit on the near side of the moon at some point where we could actually see it,” Gray said.

Furthermore, McDowell claims that monitoring deep space mission traces like these is tricky.

The moon’s gravity might modify an object’s course during flybys, causing confusion. And, except for the databases “cobbled together” by himself, Gray believes there are none widely available.

“We are now in an era where many countries and private companies are putting stuff in deep space, so it’s time to start to keep track of it,” McDowell said. “Right now, there’s no one, just a few fans in their spare time.”