Scientists studying Greenland’s massive ice sheet have discovered something astonishing: parts of the ice deep underground appear to churn and rise in plume-like structures, behaving more like molten rock than frozen solid.

Using radar imaging and advanced computer simulations, researchers found evidence of thermal convection happening inside the ice sheet. Convection is the same physical process responsible for the slow churning of Earth’s mantle beneath the crust. Until now, scientists didn’t expect it to occur inside ice.

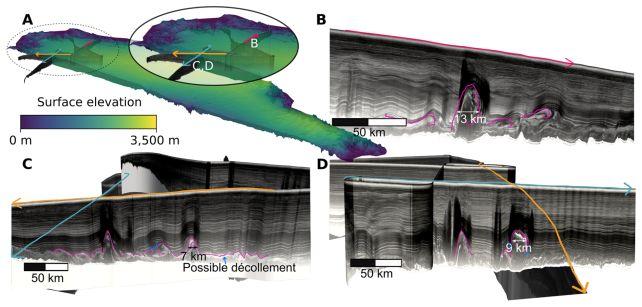

The Greenland ice sheet covers about 80 percent of the island and is up to 2.5 kilometers thick. Radar scans revealed strange upward-bulging structures deep within the ice layers – formations that couldn’t be explained by surface features or bedrock.

To solve the mystery, researchers created digital models simulating the ice sheet’s internal physics. They discovered that when the bottom layer of ice becomes slightly warmer and softer, heat from Earth’s interior can cause slow upward flow – similar to rising plumes in boiling liquid, according to the study published here.

Example plume structures from northern Greenland, mapped from radar surveys. (Law et al., The Cryosphere, 2026)

These rising columns of ice push and warp the layers above them, creating the exact patterns seen in radar images.

The source of the heat is not volcanic activity but Earth’s natural geothermal energy. Tiny amounts of heat continuously flow upward from radioactive decay inside Earth’s crust and leftover heat from the planet’s formation. Over thousands of years, this heat can gradually soften deep ice enough to trigger convection.

Importantly, the ice isn’t melting or turning into liquid. It remains solid, but it flows extremely slowly – over timescales of thousands of years.

This discovery could significantly improve scientists’ ability to predict how Greenland’s ice sheet will evolve and contribute to future sea-level rise. Understanding internal ice dynamics is critical because Greenland contains enough frozen water to raise global sea levels dramatically if fully melted.

Researchers say the finding challenges long-held assumptions about ice behavior and reveals that even seemingly stable ice sheets can have complex, dynamic interiors.