In a recent development, scientists claim to have potentially unraveled the ‘origin story’ of Egypt’s iconic Great Sphinx in Giza. This ancient monument, which features a human face on a lion-like body, has long been a subject of historical and geological debate. While historians generally agree that the face was skillfully carved by ancient stonemasons, experts have pondered since the 1980s whether desert winds might have played a role in shaping the Sphinx’s overall body.

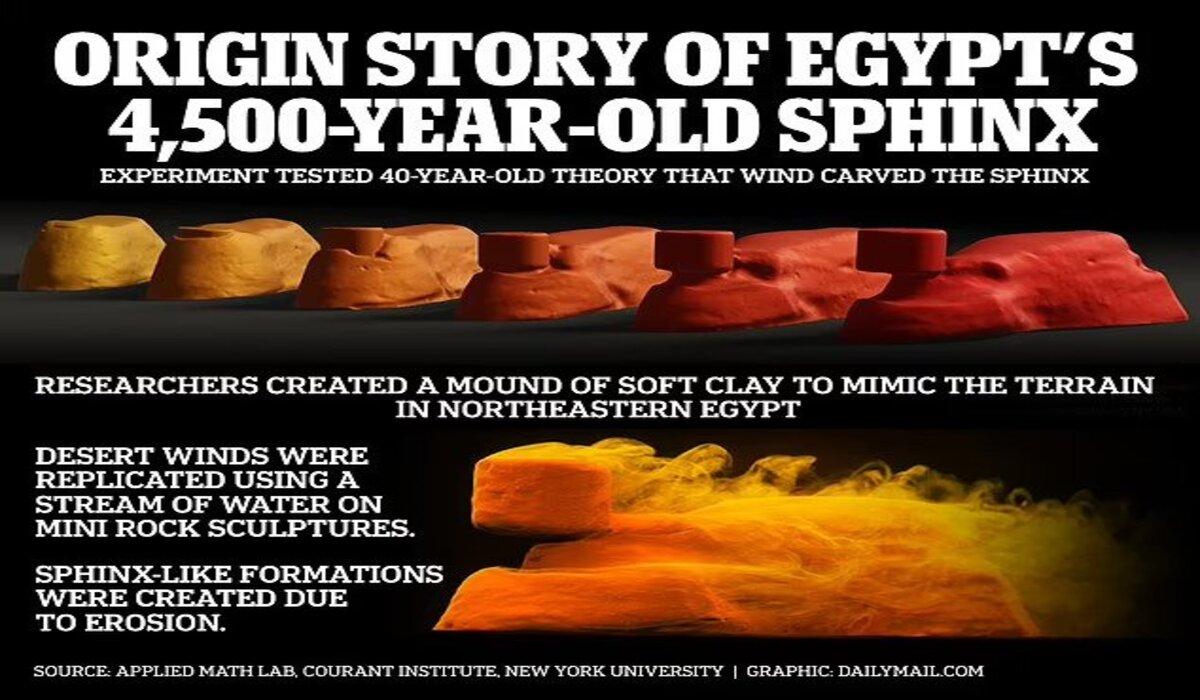

To investigate this theory, a study conducted by New York University employed a unique approach. Researchers created miniature lion-like sculptures from clay and utilized fluid dynamics to mimic the potential effects of erosion.

Their experiment aimed to determine if natural rock formations in the area could have inspired the ancient Egyptians to create the Sphinx. Lead author Professor Leif Ristroph shared their findings, stating, “Our laboratory experiments showed that surprisingly Sphinx-like shapes can come from materials being eroded by fast flows.”

The foundation for this study was a theory proposed by geologist Farouk El-Baz in 1981. El-Baz suggested that the initial form of the Sphinx was a flat-topped shape gradually eroded by the relentless winds of the desert. He further hypothesized that the builders of the pyramids at Giza were well aware of these natural processes and constructed their pointed stone structures to endure, much like the nearby hills.

El-Baz believed that the pyramids were designed to harmonize with their windy environment and that alternative shapes, such as cubes or rectangles, would have succumbed to wind erosion long ago. Additionally, he theorized that yardangs, unusual rock formations shaped by wind-blown dust and sand, might have risen on the Giza Plateau, potentially inspiring the Sphinx’s creation.

El-Baz speculated that ancient engineers, seeking to honor their king, reshaped the yardang into the iconic Sphinx, giving it a lion-like body reminiscent of forms found in the desert. To achieve this, they dug a moat around the natural protrusion.

The recent study aimed to replicate these yardangs by using soft clay mixed with harder, less erodible materials. They subjected these formations to a fast-flowing stream of water to simulate the effects of wind erosion, ultimately achieving a Sphinx-like appearance. The harder materials formed the head of the lion, while other features such as the neck, paws, and back gradually developed.

Professor Ristroph believes that their results provide a straightforward theory for how Sphinx-like formations can originate from erosion. Moreover, they discovered that rock formations are not homogenous or uniform in composition, and unexpected shapes emerge due to how flows are diverted around the harder or less erodible parts.

The Great Sphinx, according to most Egyptologists, represents King Khafra, though some argue that it could honor his father, Khufu, or his elder brother, Djadefre. The construction of the Sphinx is estimated to have taken place between 2550 BC and 2450 BC, but the evidence linking it to Khafra remains somewhat circumstantial and ambiguous.

This remarkable monument remained hidden for centuries until 1817 when an excavation led by Italian archaeologist Giovanni Battista Caviglia uncovered its chest. It was not until 1887 that the chest, paws, altar, and plateau were entirely visible, allowing the world to marvel at the enigmatic beauty of the Great Sphinx of Giza.