Canned salmon have unwittingly become guardians of Alaskan marine ecology, harboring decades of preserved natural history within their briny confines. Parasites, often overlooked, play a vital role in ecosystem dynamics. However, understanding their impact requires retrospective tracking, a challenge Natalie Mastick and Chelsea Wood from the University of Washington endeavored to overcome.

Their journey began with an unexpected offer from the Seattle Seafood Products Association: dusty, expired cans of salmon dating back to the 1970s. Seizing the opportunity, Mastick and Wood recognized these cans as more than just culinary artifacts—they were a treasure trove of preserved marine parasites, providing insights into Pacific Northwestern ecosystems.

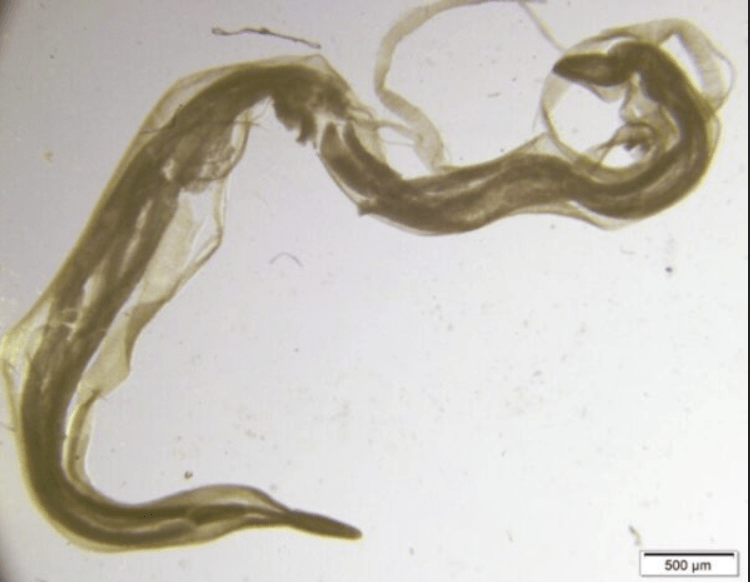

Despite the initial discomfort associated with finding worms in canned fish, these marine parasites, known as anisakids, are harmless to humans post-canning. In fact, their presence serves as an indicator of ecosystem health, tracing a complex life cycle intertwined with the marine food web.

Anisakids enter through krill, ascend through the food chain, and eventually find their way into salmon and marine mammals, completing their life cycle.

Analyzing 178 cans spanning 42 years, Mastick and Wood observed an increase in worm populations in certain salmon species over time, suggesting a robust ecosystem with ample hosts for the parasites. However, the stable levels of worms in other species posed intriguing questions, hinting at potential differences in parasite species preferences.

Despite challenges in species identification due to the canning process, Mastick and Wood’s innovative approach illuminated trends in parasite dynamics, offering a unique glimpse into historical ecological shifts. This unconventional method of ecological analysis has the potential to unveil a wealth of scientific discoveries, proving that sometimes, the most unexpected sources hold the keys to understanding complex ecological systems.

In essence, Mastick and Wood’s exploration of dusty old cans has opened a proverbial “can of worms,” revealing a rich tapestry of ecological insights preserved within the unlikeliest of archives.