A recent study led by Dr. Nicholas Cowan, an atmospheric physicist at the UK Centre for Ecology and Hydrology in Edinburgh, delves into an unexpected contributor to greenhouse gas emissions: human breath. While common environmental practices, such as reducing meat consumption and adopting sustainable transportation, are widely acknowledged, the study sheds light on the less intuitive aspect of human respiration impacting climate change.

The focus of the investigation is on two gases expelled during exhalation, namely methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O), constituting up to 0.1% of the United Kingdom’s greenhouse gas emissions. Notably, this calculation excludes emissions from additional sources like burps, flatulence, or skin-related emissions. Unlike carbon dioxide (CO2), which is absorbed by plants through photosynthesis, methane and nitrous oxide remain in the atmosphere, contributing to the greenhouse effect.

In the respiratory process, humans inhale oxygen and exhale carbon dioxide. However, the study zeroes in on the lesser-discussed methane and nitrous oxide, which, though released in smaller quantities, have a more substantial impact on global warming. While CO2 emissions from breath are effectively offset by plant absorption, the same does not hold true for methane and nitrous oxide.

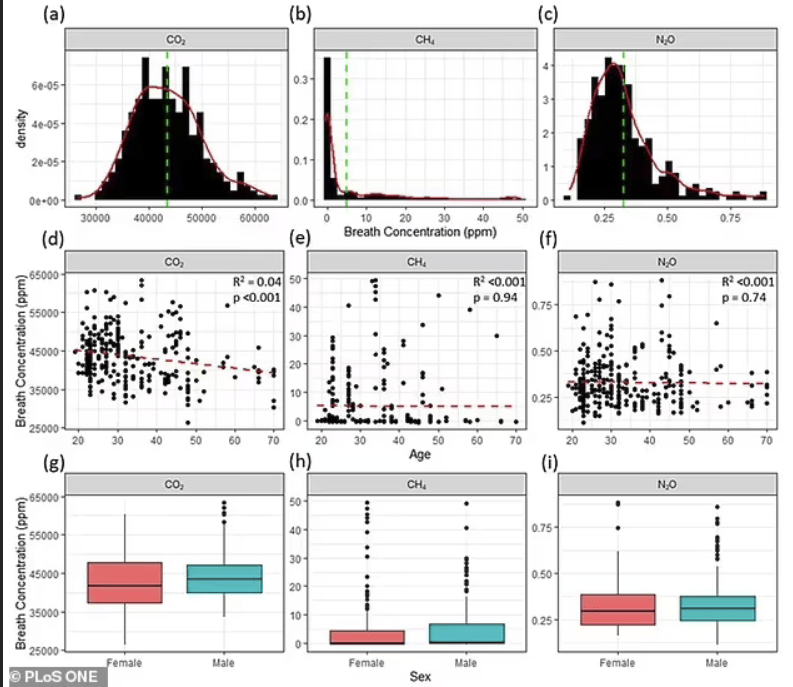

The research, involving 104 adult volunteers from the UK, examined breath samples obtained through participants inhaling deeply and exhaling into sealable plastic bags. The findings indicated that nitrous oxide was present in the breath of all participants, while methane was identified in only 31% of the samples. Those lacking methane in their breath were likely compensating through other means, primarily flatulence.

An intriguing demographic observation emerged from the study: individuals exhaling methane were more frequently female and over 30 years old. However, the rationale behind this correlation remains undetermined. The study estimates that human breath contributes 0.05% of the UK’s methane emissions and 0.1% of nitrous oxide emissions.

It is essential to clarify that these percentages specifically pertain to these individual gases and do not offer a comprehensive overview of the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions. The study did not establish a direct connection between the gases in breath and dietary preferences, despite known environmental implications associated with meat consumption.

In light of these findings, researchers advocate for increased attention to emissions of methane and nitrous oxide from human breath, asserting that a broader exploration could yield insights into the repercussions of an aging population and evolving dietary patterns. The study challenges the traditional perception of breath emissions as negligible and emphasizes the need for a comprehensive understanding of all potential contributors to greenhouse gas emissions.