In a study from Australia’s RMIT University, scientists have discovered that charred coffee grounds can make concrete up to 30% stronger. This unexpected innovation could tackle two global challenges at once – the massive waste from coffee consumption and the increasing demand for environmentally sustainable construction materials.

Each year, humanity generates nearly 10 billion kilograms (22 billion pounds) of coffee waste, most of which ends up rotting in landfills and releasing harmful greenhouse gases. Meanwhile, the booming construction industry continues to deplete natural sand resources and increase carbon emissions. The RMIT team’s breakthrough offers a promising circular-economy approach to mitigate both problems.

Coffee grounds may seem harmless, but their disposal contributes significantly to climate change. As engineer Rajeev Roychand from RMIT explained when the research was first published in 2023: “The disposal of organic waste poses an environmental challenge as it emits large amounts of greenhouse gases, including methane and carbon dioxide, which contribute to climate change.”

At the same time, global demand for concrete and sand is soaring, driven by urban expansion. Extracting sand from riverbeds and coastal ecosystems has become an unsustainable practice.

“The ongoing extraction of natural sand around the world has a big impact on the environment,” said RMIT engineer Jie Li. “With a circular-economy approach, we could keep organic waste out of landfill and also better preserve our natural resources like sand.”

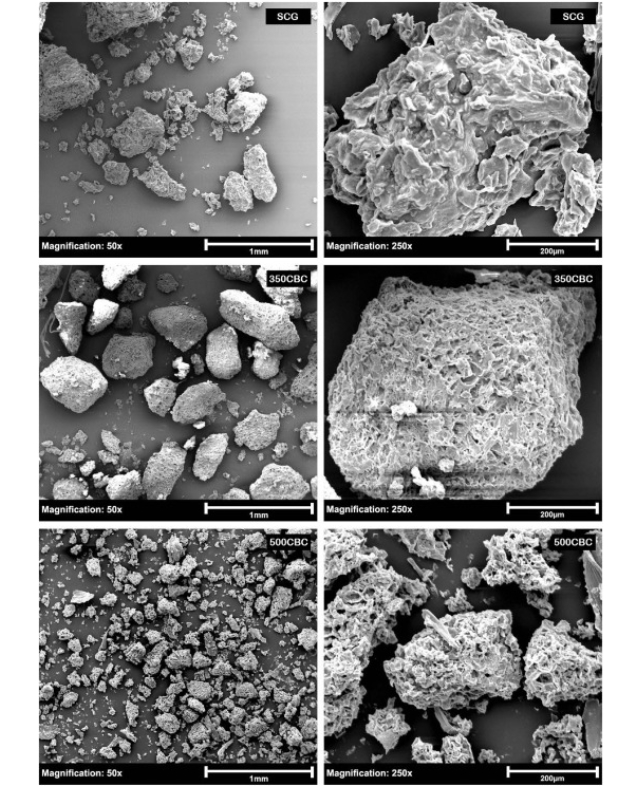

Simply mixing organic waste into concrete doesn’t work unprocessed coffee grounds release chemicals that weaken the cement structure. To solve this, researchers used a process called pyrolysis, where they heated coffee waste to about 350°C (660°F) in a low-oxygen environment.

This low-energy method transformed the grounds into a carbon-rich biochar, a porous material capable of bonding with cement particles. The resulting concrete was up to 30% stronger than standard formulations. Interestingly, when the coffee was heated to a higher temperature 500°C, the resulting biochar wasn’t as effective, suggesting that lower temperatures yield better structural benefits.

Scanning electron microscope images from the study show the porous microstructure of these coffee-derived biochar particles, which help interlock with the cement matrix and improve overall strength.

While the early results are promising, the researchers emphasize that this is just the beginning. The team is now testing how the coffee-infused concrete performs under freeze–thaw cycles, abrasion, water absorption, and other stressors to assess its long-term durability.

They’re also expanding the research to include biochars made from other organic waste materials such as wood, food scraps, and agricultural residues potentially opening the door to a new generation of sustainable construction materials.

For engineer Shannon Kilmartin-Lynch, the project’s motivation runs deeper than material science: “Our research is in the early stages, but these exciting findings offer an innovative way to greatly reduce the amount of organic waste that goes to landfill,” Kilmartin-Lynch said.

“Inspiration for my research, from an Indigenous perspective, involves Caring for Country ensuring there’s a sustainable life cycle for all materials and avoiding things going into landfill to minimize the impact on the environment.”