Scientists have found a mysterious genetic mutation that effectively negates the sensation of pain in people. This enables people with the rare anomaly to preserve effortlessly through extreme physical discomfort. The gene variant is identified in an Italian family who feels no pain even when severely injured. This could help scientists find new treatments for chronic pain that mimic the family’s unusual gift.

“We have spent several years trying to identify the gene that is the cause of this,” molecular biologist James Cox from University College London told. “This particular disorder may only be in one family.”

The Marsilis, go about their usual daily lives with something like a real-life superpower. All thanks to a rare genetic point mutation which has spanned at least three generations. The mutation means that they feel a little or no pain at all from serious issues like burns or broken bones. They don’t even realize that they have hurt themselves so bad.

“Sometimes they feel pain in the initial break but it goes away very quickly,” Cox told. “For example, [52-year-old] Letizia broke her shoulder while skiing, but then kept skiing for the rest of the day and drove home. She didn’t get it checked out until the next day.”

The variant shared by the family was isolated in the Marsilis DNA from blood samples and is located in a gene called ZFHX2. While it is not entirely clear how the mutation works, the team hypothesizes that the variant disrupts how ZFHX2 regulates other genes that have been linked to pain signaling. That disruption gives the Marsilis what’s known as congenital insensitivity to pain, however, their phenotype is so remarkable the researchers have named a whole sub-type of the condition, ‘Marsilis syndrome’, named after the family.

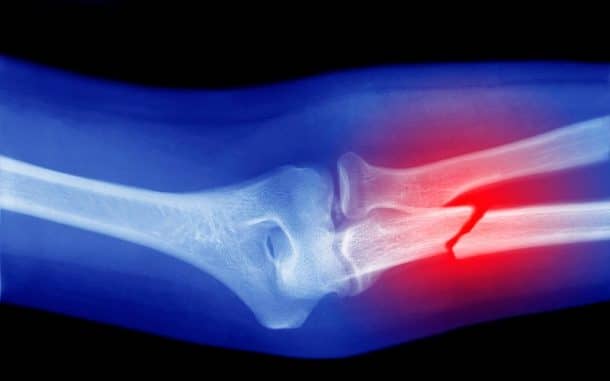

In this case, the blessing can also be a curse. The failure to accurately interpret what pain represents can mean they are not aware of a serious injury that may need immediate medical attention. Letizia Marsili’s 24-years old son, Ludovico, is fond of football. This condition masks his injuries incurred by the sport. “He rarely stays on the ground, even when he is knocked down. However, he has fragility at the ankles and he often suffers distortions, which are microfractures,” said Letizia Marsili.

“In fact, recently X-rays have shown that he has lots of microfractures in both ankles.” Other family members have experienced similar problems, with Letizia’s 78-years old mother experiencing fractures that are only much later diagnosed means that they harden naturally but did not heal properly. The gene mutation also affects their ability to detect extreme temperatures, putting them at greater risk of burning themselves or failing to register things like ice water.

Despite the risks inherent in feeling no pain, the family seems grateful to be missing out on what is a source of misery for so many others. “From day to day we live a very normal life, perhaps better than the rest of the population, because we very rarely get unwell and we hardly feel any pain,” said Letizia. “However, in truth, we do feel pain, the perception of pain, but this only lasts for a few seconds.”

Once the researchers isolated the ZFHX2 mutation by way of exome sequencing the team used animal experiments to see how the variant affects pain processing in mice. Animals bred to not have the gene at all showed reduced pain sensitivity when the pressure was applied to their tails but were still receptive to high heat. When other mice were bred to possess the ZFHX2 mutation, they exhibited the same low sensitivity to high heat that the Marsilis have – something the team is hopeful may provide new directions into treatments for millions who live with chronic pain in routine.

“By identifying this mutation and clarifying that it contributes to the family’s pain insensitivity, we have opened up a whole new route to drug discovery for pain relief,” says the researcher, Anna Maria Aloisi, University of Siena in Italy. “With more research to understand exactly how the mutation impacts pain sensitivity, and to see what other genes might be involved, we could identify novel targets for drug development.”

There is still a lot to find out about how ZFHX2 is involved in pain signaling. As far as this family is concerned they won’t be hanging by the phone to know about any future discoveries. One of the researchers, sensory neurobiologist John Wood from University College London said that the family has no intention of giving up their painless existence if scientists one day find out a way to reverse the condition. “I asked them if they would like to normally sense pain,” he told, “and they said no.”