In 5 years, a major natural gas utility in California received a lot of serious major alerts about methane leaks from its facility.

Between 2016 and 2021, state authorities notified Southern California Gas Company while working with NASA to find sizable methane plumes using high-resolution remote sensors.

The pipeline repairs were completed a few days after Southern California Gas Company verified the leakage. In addition, the company fixed a valve at a compressor station lowering the amount of poisonous methane released into the atmosphere.

By 2023, two satellites carrying the remote sensors will be sent into orbit. As a result, methane leaks can now be found and measured almost anywhere using satellite technology. Additionally, within days, scientists can use AI to calculate the number of leaking pollutants.

This makes it possible for businesses to fix leaks more rapidly, and, more importantly, it makes governments and companies that misreport their emissions more accountable.

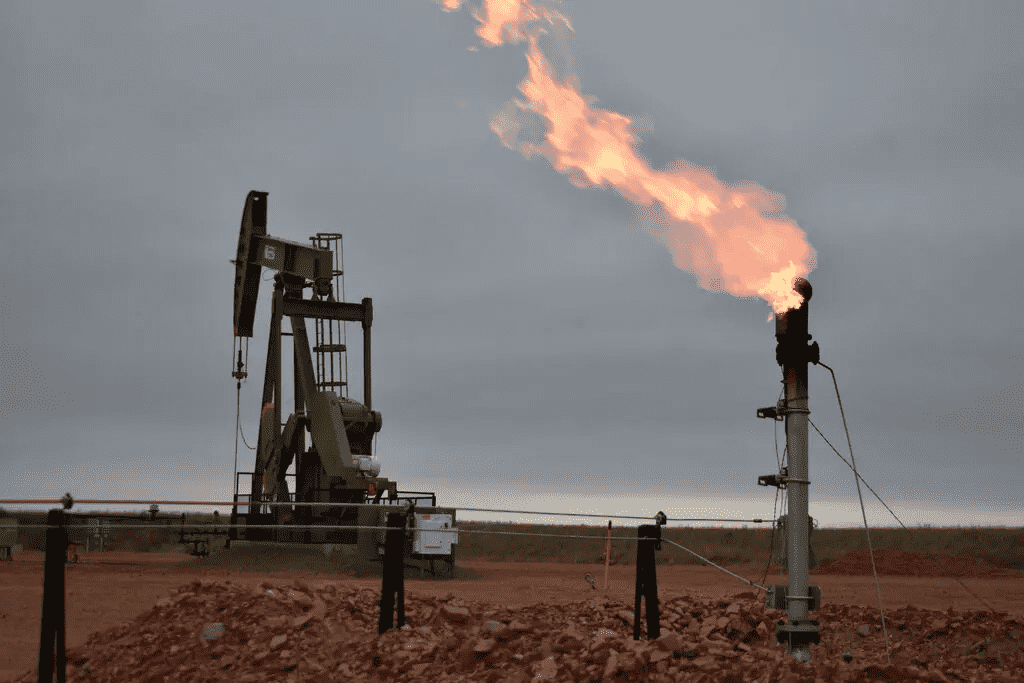

One of the quickest ways to limit global warming is to reduce methane, but it’s much more complicated than it seems to identify dangerous gas. To find methane leaks, fieldwork using jets and portable infrared cameras that expose the gas is necessary.

“In the last decade, satellites have mainly been used to quantify emissions at a large scale. That’s important, but the other key is timely, actionable data so operators can find and fix leaks and verify that they stay fixed. That’s a huge change,” said Riley Duren, the CEO of Carbon Mapper.

Working at NASA in California, Duren formed the organisation after launching the California Methane Survey. Forty-eight thousand metric tons of methane from oil, gas, landfills and manure pits were prevented from the atmosphere.

In response to questions about its performance, SoCalGas claimed that it had reduced fugitive methane emissions by 37% since 2015, principally due to frequent aerial and ground-based surveillance and a sharp fall in the release of methane during servicing.

SoCalGas senior environmental sustainability manager and planning Deanna Haines stated that the company would keep collaborating with Carbon Mapper after the latter’s satellite launch.

“Any extra set of eyes and helping identify larger leaks is really important,” he added.

This concept shows the capabilities of Carbon Mapper when it is fully deployed. But the company is not acting alone in this endeavour. In Canada’s emissions-monitoring industry, six satellites from GHGSat were in orbit, and four more were due to launch by the end of 2023. Moreover, Shell, Chevron, and TotalEnergies have also contracted GHGSat.

The US Environmental Defense Fund will also launch its satellite in 2023. MethaneSAT will cover wider regions that produce more than 80% of the world’s oil and gas.

Mark Brownstein, senior vice president of energy at the EDF, claims that MethaneSAT can find more dispersed gas sources than ESA satellites might.

Methane leaks have been identified and quantified by scientists using satellite data in the past, demonstrating the intensity and widespread of the issue.

“Timely data is important,” Brownstein said. “The idea is to inform in a way that leads to action.”