More than two decades after the Hubble Space Telescope stunned the world with its Ultra Deep Field image, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has returned to that same corner of the cosmos. As part of the JWST Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey, known as JADES, this new observation captures ancient galaxies previously hidden from view, stretching across billions of years of cosmic evolution.

The original Hubble Ultra Deep Field, released in 2004, showed around 10,000 galaxies packed into an area of sky smaller than a tenth the diameter of the full Moon. Taken using Hubble’s deepest infrared capabilities at the time, the image unveiled galaxies as they appeared over 13 billion years ago. Hubble revisited the field several times, gradually improving its reach, but was ultimately limited by its ability to see only partway into the infrared spectrum. As light from the earliest galaxies becomes redshifted by the expanding universe, it shifts beyond the range of visible light, placing it out of Hubble’s reach.

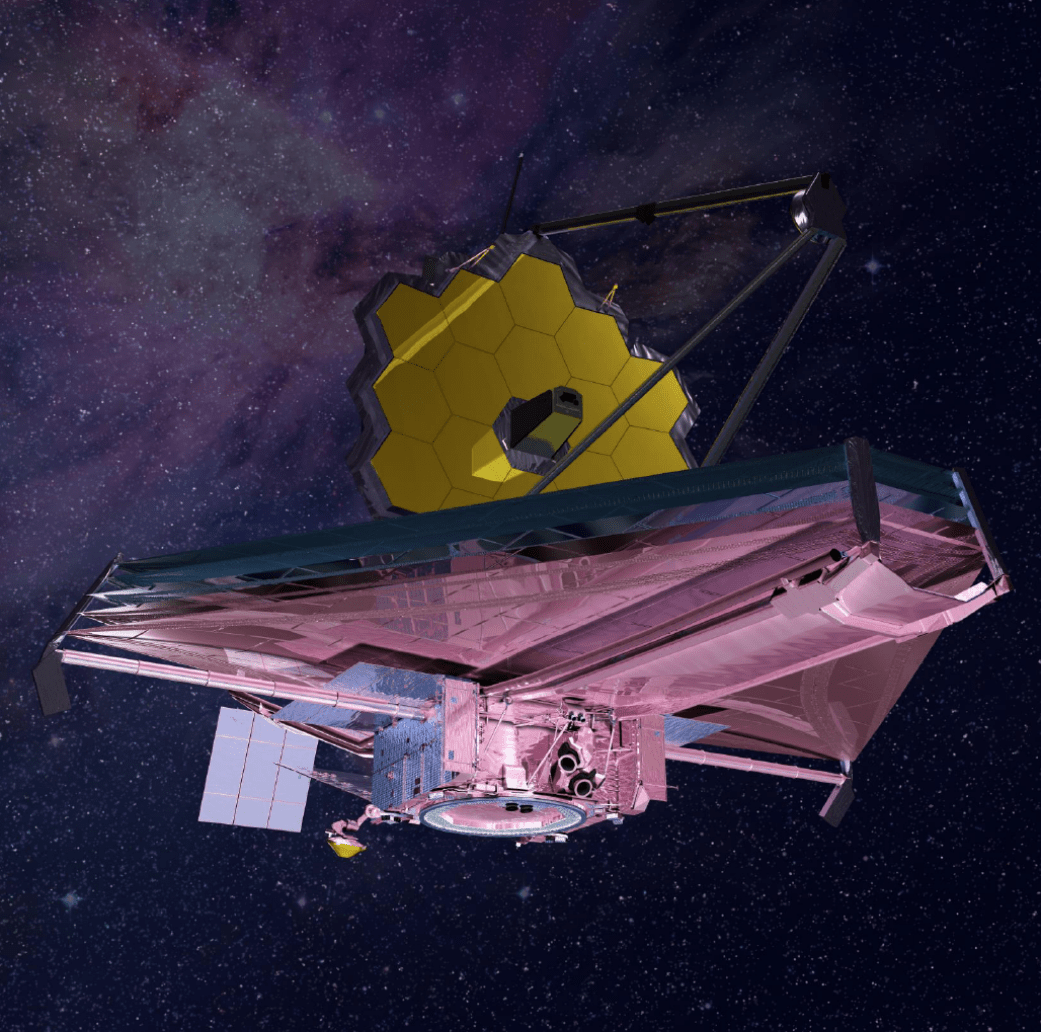

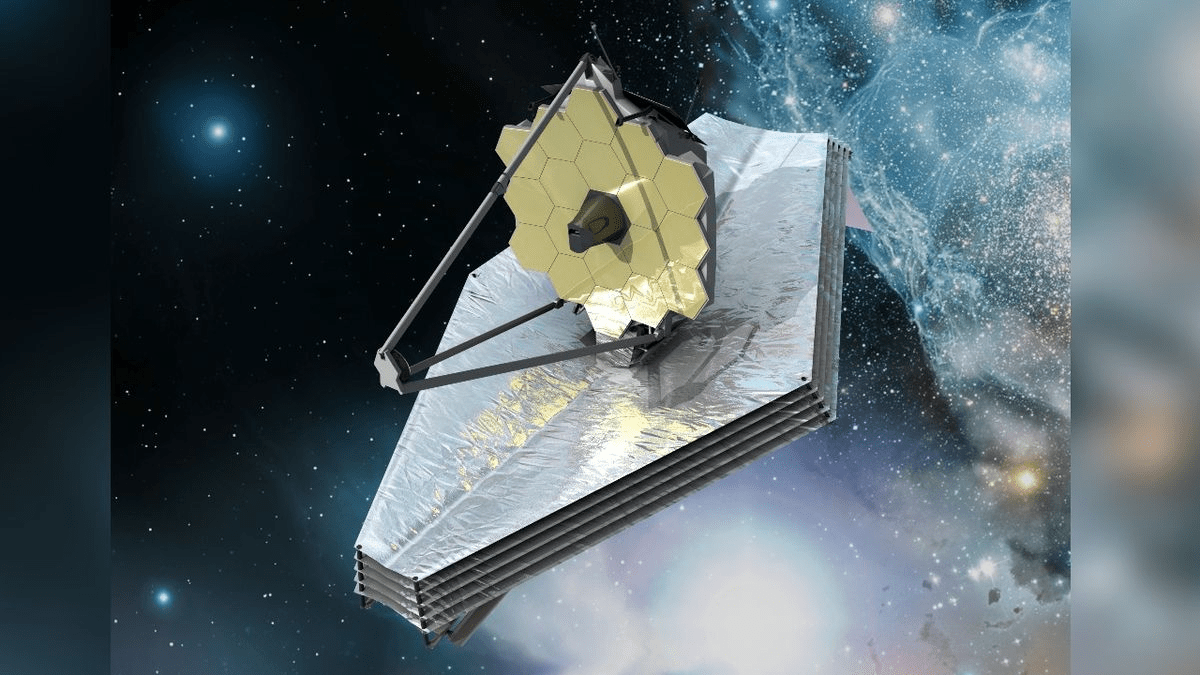

Enter the James Webb Space Telescope. With its 6.5-meter mirror and specialized instruments designed to observe infrared light, JWST was built to go where Hubble could not. In October 2022, it began taking its first deep-field images of this region using its Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam). More recently, the telescope has gone even further using its Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI), gathering new data as part of the MIDIS Deep Imaging Survey. The latest image does not cover the entire Ultra Deep Field but focuses on a subsection containing roughly 2,500 galaxies. Most of these galaxies are extremely distant, their light having traveled more than 13 billion years before reaching the telescope.

One of the filters used for this image, called F560W, centers around a wavelength of 5.6 microns and required the longest exposure of any single filter used in the project, totaling 41 hours. This remarkable depth allows astronomers to view galaxies as they were just 380 million years after the Big Bang. Although none of the galaxies in this specific image break records, they are approaching the same era as the current most distant galaxy known, MoM-z14, which dates back 280 million years after the Big Bang and lies beyond this field of view.

The combination of MIRI and NIRCam allows researchers to decode the structure and composition of galaxies in unprecedented detail. The image reveals a rich mix of galactic types. Many of the faint red galaxies in the field are either young galaxies cloaked in cosmic dust or older, evolved systems full of ancient stars that formed during the early stages of the universe. Others, with a greenish-white hue, appear as high-redshift galaxies seen during the universe’s first billion years. In contrast, the more prominent blue and cyan galaxies are relatively nearby and appear brighter in the near-infrared.

Since infrared light is beyond human vision, the image is rendered in false color. This process assigns visible colors to different infrared wavelengths, helping to visually separate objects by their distance and composition. What emerges is a cosmic mosaic that not only stuns with beauty but also contains critical clues about the timeline of galaxy formation, star birth, and the emergence of black holes in the early universe.

Astronomers are continuing to build on these observations, layering new data in an effort to chronicle the universe’s evolution from its earliest moments to the modern day. The ultimate goal is to understand when and how the first stars and galaxies formed, how massive black holes came to exist so early, and how galaxies have changed over time.