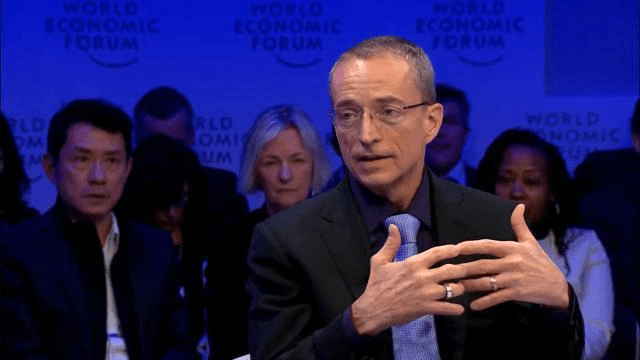

Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger recently addressed the repercussions of US-led sanctions against China during the World Economic Forum in Switzerland. The sanctions, designed to hinder China’s progress in producing advanced processors and components, have reportedly set the country back by approximately a decade, according to Gelsinger.

In his dialogue with Klaus Schwab, the founder of the World Economic Forum, Gelsinger highlighted key obstacles, particularly China’s struggle to acquire chip-making machines crucial for advancing its semiconductor industry. Gelsinger emphasized the effectiveness of the US-led strategy, asserting that China’s semiconductor industry is constrained to the “10 to 7nm range” due to its inability to procure chip-making machines from ASML in the Netherlands. While Intel and its competitors are advancing towards “2nm” and beyond, China remains hampered in its progress. Gelsinger pointed out that Intel’s Meteor Lake, initially labeled as 7nm, is closer to a 4nm process, emphasizing the substantial technological disparity.

The Intel CEO acknowledged that China won’t cease its efforts to innovate but highlighted a significant challenge: the interconnected nature of the semiconductor industry. Manufacturing chips requires a collaborative effort, involving parts, supplies, and expertise from global companies. Gelsinger outlined the dependencies, such as machines from the Dutch, chemicals from Japan, and mask-making expertise from companies like Intel, all of which are currently inaccessible to China. Even with one rogue supplier, China would lack the essential collective ingredients for chip production.

Gelsinger asserted that existing export policies would likely keep China trailing behind Intel, Samsung, and TSMC by approximately ten years concerning advanced chip designs. However, he acknowledged that China is exploring workarounds. For instance, Huawei recently announced a 5nm ARM SoC for laptops, a development that surprised regulators. Despite these challenges, it remains uncertain how long it will take for China to master advanced chip designs, with questions arising about its potential progression to a 3nm chip in the future. While highlighting the current setback, Gelsinger’s comments also hint at the adaptability and resilience of China’s semiconductor industry.