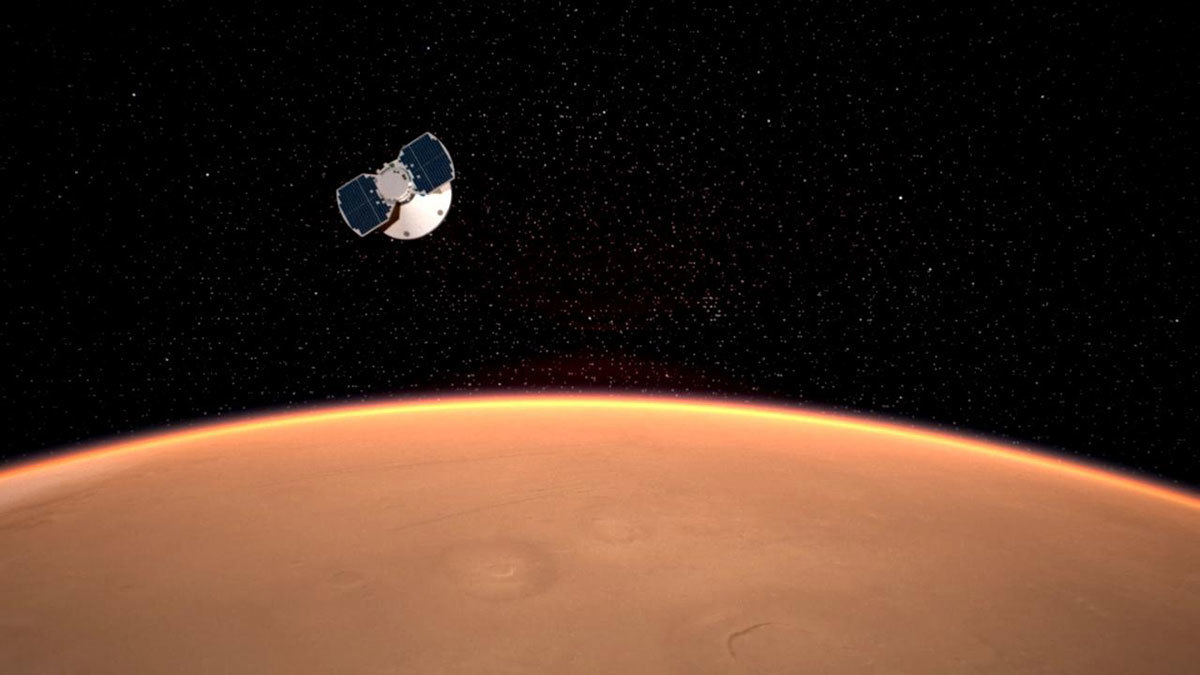

Dust is stacking up on NASA’s full-fledged Mars lander “Insight”, hoping an angel will soon blow it away. Unfortunately, this summer will be the period when it enters an eternal hibernation.

“It looks like in the summer time frame — late-spring, early-summer — is when it becomes impossible to power the seismometer, at least power around the clock,” says Bruce Barnerdt, principal investigator of the InSight mission.

In a few months, InSight will most likely be unable to undertake any further scientific investigations, and the spacecraft itself will be exhausted. The thing is, NASA, and every single scientist and engineer who worked on or with InSight, saw this coming.

Throughout InSight’s two-year mission on Earth, all the probe’s various research objectives were met. Unfortunately, the lander’s heat probe was unable to function due to some soil, which was the only major stumbling block. Fortunately, the robot’s seismometer took the initiative and offered an alternative technique of gauging heat flow.

“A seismometer is a very, very complex instrument. And the whole idea that you can shoot it off from a rocket on Earth have it go through the atmosphere of Mars at supersonic speed, touch down and then have it couple to the surface. I mean, we don’t even drop seismometers out of airplanes on Earth,” says Tom Wagner, a program scientist at NASA’s Planetary Science Division.

“It’s an amazing feat of engineering and science. And it’s ensured that InSight has been “a success, by any measure.”

The mission was set to terminate in December 2020. On the other hand, NASA agreed to continue the show for another two years. Unfortunately, due to the accumulation of dust on its solar panels, InSight is incapable of making it until year-end.

“It is understandable that curious members of the public want to know why nothing was done to prevent this dust build-up in the first place,” says Simon Stähler, a seismologist at ETH Zürich in Switzerland and member of the InSight science team.

Admittedly, previous space missions have lasted a lot longer than they were supposed to. So why has the end of InSight reached so abruptly? Some of it is simply coincidence: the Martian desert’s instability has dumped rather more dust on its solar panels than the winds have decided to erase. The other factor at play answers a popular suggestion: why not just create a way for the lander to blow away the dust?

NASA approves missions through a series of plans, one of which is the Discovery program. With a budget of roughly $600 million, these programmes are cost-effective. However, since InSight is part of the Discovery, it had access to approximately $600 million, which suggests you won’t be able to achieve all you want.

No matter how much funding a space mission is given, when designing it, “you have to make all kinds of compromises all the time,” says Barnerdt.“If one mission doubles its budget, something else has to go away.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ef/0e/ef0e7943-9f71-4a07-b310-1c0e02d0f5bb/mars_insight.jpg)

The team sought to demonstrate that InSight would achieve its scientific objectives while modelling it. As a result, solar panels are less expensive than Perseverance rover-style nuclear batteries, also called radioisotope thermoelectric generators, or RTGs. Previously, it was cheaper to build, but the source of free plutonium from nuclear weapon manufacturing has largely dried up since the Cold War.

“NASA is able to produce one RTG per decade, roughly,” says Stähler, each costing about $100 million.

Shouldn’t anything as simple as a brush for cleaning the solar panels have been included in the design? However, these solar panels are extremely thin, and a brush may temporarily incapacitate them. In addition, adding a brush to InSight’s toolkit would have taken a significant amount of time and money.

InSight was planned to fulfil many particular tasks in two Earth years, which tried-and-true solar panels could do within the financial limitations. It was a success, and every mission that follows will be built on its scientific foundation.

This year, though, it will wither and die. InSight mission’s particular design was not finalised until 2006. Using one or more geological instruments to map out Mars started in the 1990s. It’s sad to witness a worthy goal fulfiled, only to watch the instrument slowly degrade in a wasteland far away.

“I’m completely emotionally attached to this thing. It’s really been a part of my life for almost 30 years,” says Barnerdt.

“To think that it’s all going to come to an end in a matter of months…I actually try not to think about it very much, but when I do, it really does make me sad.”