For most of the past century, nuclear fusion has carried the reputation of being a perfect energy source that was always decades away. The physics was sound, but translating star-level reactions into a stable, Earth-bound power plant proved relentlessly difficult. That perception is now beginning to change as recent breakthroughs push fusion from theoretical promise toward practical engineering, according to Tech Spot.

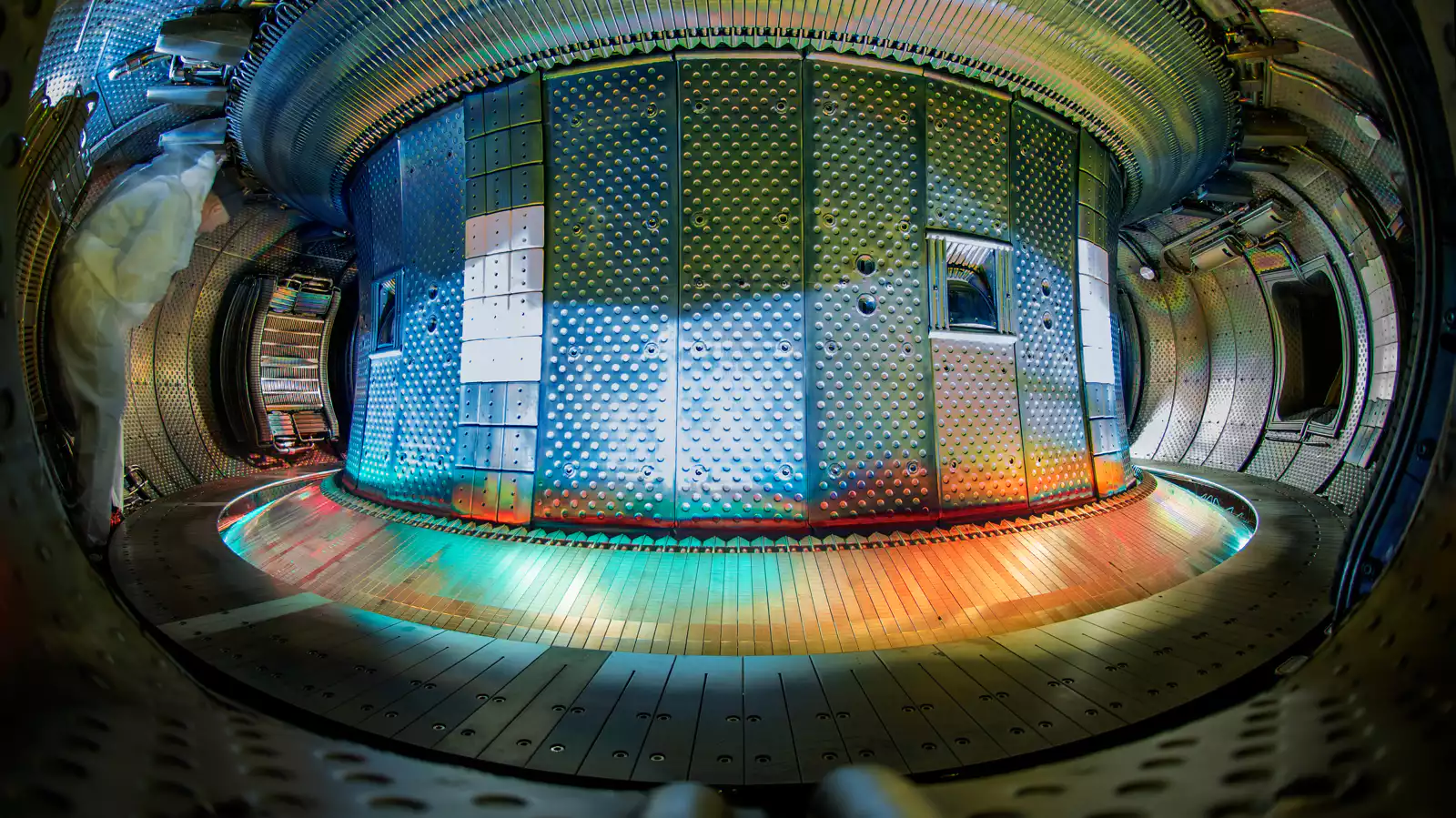

At the heart of this shift are tokamaks, donut-shaped reactors that use powerful magnetic fields to confine plasma heated to more than 100 million degrees Celsius. At these temperatures, hydrogen nuclei can fuse into helium, releasing immense energy. The challenge has never been ignition alone, but stability: holding that plasma together long enough to produce more energy than the system consumes.

Over the last few years, several major facilities have crossed milestones once thought unreachable. China’s Experimental Advanced Superconducting Tokamak demonstrated operation beyond the Greenwald density limit, showing that higher plasma densities can be sustained without triggering instability. In Europe and Asia, France’s WEST reactor and South Korea’s KSTAR have both extended plasma confinement times, turning brief flashes into sustained reactions that can be studied and refined.

These advances feed directly into ITER, the largest fusion experiment ever attempted. The 23,000-ton reactor under construction in southern France is designed to prove net energy gain at scale. In late 2025, the delivery of ITER’s final central solenoid module, the most powerful magnet ever built, marked a major step toward that goal. Despite years of delays, ITER now stands as a focal point for global fusion research, backed by more than 30 countries.

Artificial intelligence is accelerating progress further. Machine learning systems are being used to predict plasma disruptions before they occur, adjust magnetic fields in real time, and extract more value from experimental data. What once required years of trial-and-error can now be iterated in months, compressing a timeline that historically stretched across generations.

Materials remain the toughest barrier. Fusion reactions bombard reactor walls with high-energy neutrons that can weaken or destroy conventional metals. To address this, new research centers are focused on developing alloys, ceramics, and composites that can survive extreme heat and radiation. Facilities like MIT’s Laboratory for Materials in Nuclear Technologies, launched in 2025, aim to bridge the gap between laboratory discovery and industrial-scale durability.

Money and confidence are also flowing in. Private investment in fusion surged dramatically over the past decade, driven in part by energy-hungry technology companies seeking long-term, carbon-free power. Governments facing climate targets are increasingly viewing fusion not as a gamble, but as a strategic necessity.

Fusion is still not plug-and-play. Economic viability, regulatory frameworks, and engineering scale-up all remain unresolved. Yet for the first time in decades, progress is no longer defined by isolated experiments, but by a coordinated, global push that is steadily removing long-standing barriers.

After seventy years of setbacks, fusion energy no longer feels like a perpetual promise. It now looks like a difficult, expensive, but achievable engineering problem—one that may finally be entering its decisive phase.