Besides making weekly or monthly forecasts, weather models are also used to make hourly predictions that are called nowcasting. This is done by a Google-backed artificial intelligence company DeepMind that is making progress in predicting hourly precipitation.

This model is ranked first when it comes to usefulness and accuracy in 89 percent of cases. It makes use of machine learning called generative modeling that creates new data points after being trained on existing ones.

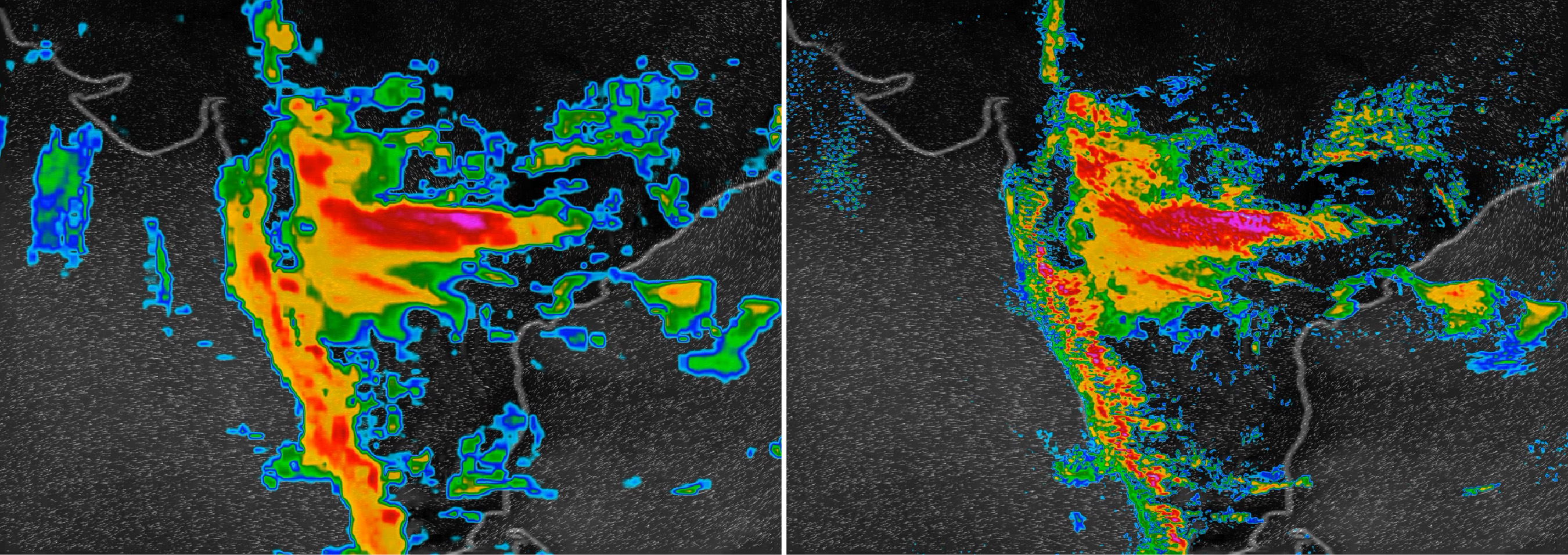

The new model is called DGMR (Deep Generative Model of Rainfall). The main objective for it is to foretell the probability of precipitation across the next one to two hours. The model is approved by more than 50 meteorologists at the Met Office in the UK.

“This collaboration between environmental science and AI focuses on value for decision-makers, opening up new avenues for the nowcasting of rain, and points to the opportunities for AI in supporting our response to the challenges of decision-making in an environment under constant change,” writes the DeepMind Nowcasting Team in a blog post.

Advanced nowcasting tools like pySTEPS are used to make numerical weather prediction (NWP) approaches. These are strong models, but they’re more accurate over the longer term.

“These models are really amazing from six hours up to about two weeks in terms of weather prediction, but there is an area – especially around zero to two hours – in which the models perform particularly poorly,” Suman Ravuri, a staff research scientist at DeepMind, told The Guardian.

There is still a great amount of work that needs to be completed before this technology can be widely implemented and scaled. The team is working on improving the results of the forecasts.

“No method is without limitations, and more work is needed to improve the accuracy of long-term predictions and accuracy on rare and intense events,” writes the team.

“Future work will require us to develop additional ways of assessing performance, and further specializing these methods for specific real-world applications.”

The research has been published in Nature.