Scientists have developed an implantable device comprising stem cells designed to grow into insulin-secreting cells. This will help the case of diabetes type 1 in humans. Experimental trials were carried out that showed the results to be safe, well-tolerated and mildly effective. It also gave hope that with more advancement, it will lead to a “functional cure.”

In 2017, a Phase 1/2 human clinical trial was carried out to test an experimental implant designed to replace the missing insulin cells in type 1 diabetics. It was not a straightforward cure for the disease. In fact, it aided the body in maintaining normal blood sugar levels by compensating for missing insulin-producing cells.

Later, pancreatic islet cells from donors are transplanted patients with type 1 diabetes. However, in this approach, the dependence on donor cells is eliminated as it uses human pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) engineered to develop into pancreatic cells.

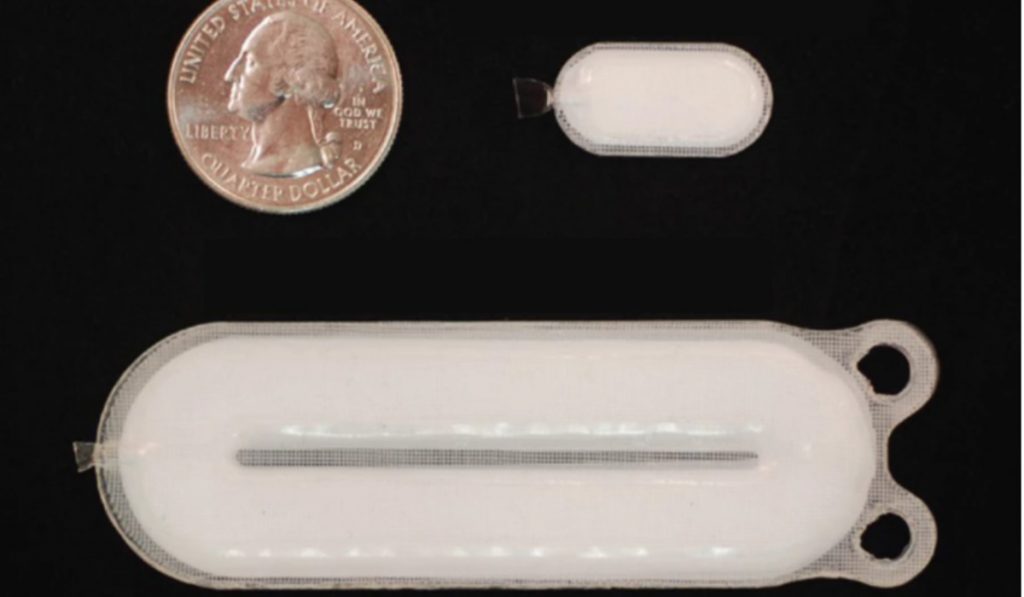

The stem cells are loaded into a device and implanted into diabetic patients. The cells then transform into insulin cells.

“The present study demonstrates definitively for the first time to our knowledge, in a small number of human subjects with type 1 diabetes, that PSC-derived pancreatic progenitor cells have the capacity to survive, engraft, differentiate, and mature into human islet-like cells when implanted subcutaneously,” says Howard Foyt, from ViaCyte, the company working on the innovation.

26 patients were treated with the device. After one year, they spent an average of 13 percent more time in a healthy blood glucose range than they did before. Also, their insulin requirements were cut by an average of 20 percent.

David Thompson, a researcher in the team of the Vancouver General Hospital Diabetes Centre, states that the treatment is currently being improved so it can deliver higher volumes of PSCs for better results.

“Because of this initial success, we are now implanting larger numbers of cells in additional patients, and we hope that this will result in a significant reduction or even elimination of the need for patients to take insulin injections in the near future,” says Thompson.

In addition, constant immunosuppressive medications are always needed along with the device. Without them, the device will be rejected.

Diabetes researchers Eelco de Koning and Francoise Carlotti call the new findings a milestone but also pose some queries that will need to be addressed from the trials’ results like which part of the body is ideal for the implant? Are immunosuppressive drugs viable for long-term?

“The clinical road to wide implementation of stem cell-derived islet replacement therapy for T1D is likely to be long and winding,” write de Koning and Carlotti. “Until that time, donor pancreas and islet transplantation will remain important therapeutic options for a small group of patients. But a landmark has been set. The possibility of an unlimited supply of insulin-producing cells gives hope to people living with T1D. An era of clinical application of innovative stem-cell-derived islet replacement therapy for the treatment of diabetes has finally begun.”