Picture traveling at nearly 400 miles per hour across long distances on a train that doesn’t even touch the ground. There are no rattling wheels, no sudden jolts, only a smooth, almost silent glide. This is the promise of magnetic levitation, or maglev, trains. While countries like Japan and China are already breaking speed records and putting this futuristic transport into service, projects in the West are still struggling to deliver even conventional high-speed rail.

The roots of high-speed rail stretch back to 1964, when Japan launched the Shinkansen bullet train and proved that safe, efficient, and rapid travel on rails was possible. China took the idea further, building the largest high-speed rail network in the world, where sleek trains now cruise at 300 to 350 kilometers per hour, or around 186 to 217 miles per hour. This success laid the foundation for an even greater leap forward: magnetic levitation.

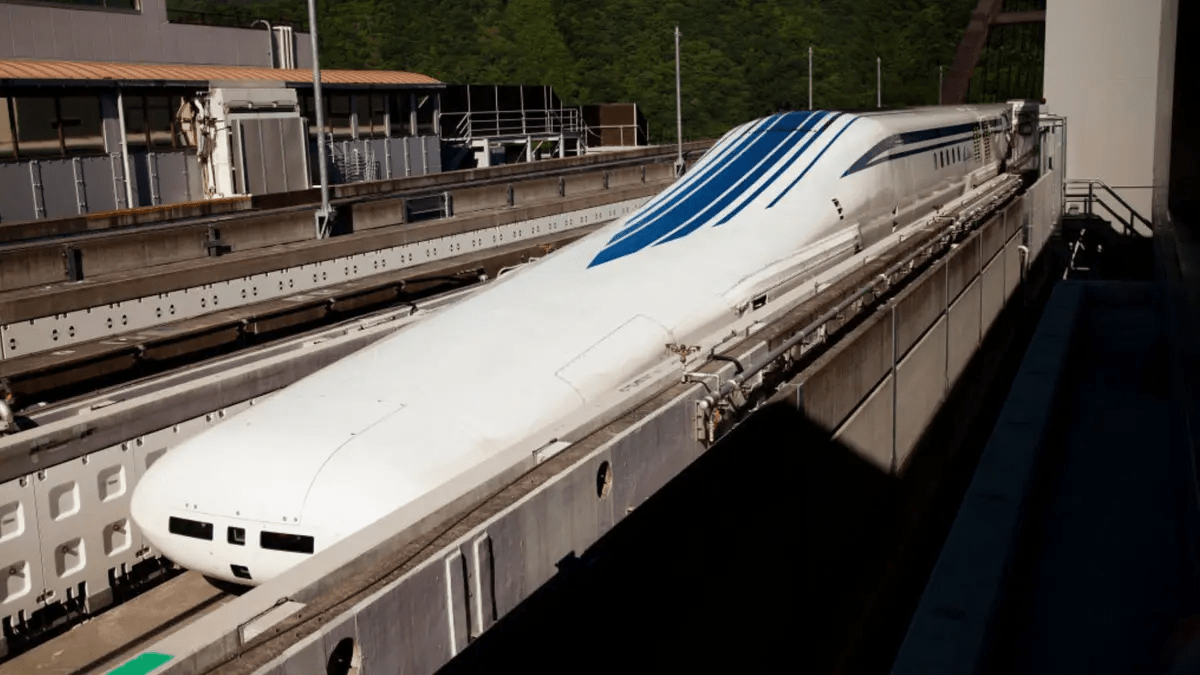

In 2004, China shocked the world with the Shanghai Maglev, the first commercial maglev line to operate in daily service. Using German technology, it connects Pudong Airport with downtown Shanghai, a distance of 30 kilometers covered in just seven and a half minutes. With peak speeds of 431 kilometers per hour, or 268 miles per hour, it remains the fastest commercial train in operation today. Japan, however, has been steadily pursuing its own maglev since the 1970s. Its superconducting maglev project, known as SCMaglev, set a world record in 2015 when an experimental train reached 603 kilometers per hour, or 374 miles per hour. Construction is underway on a line between Tokyo and Nagoya, due to open in the 2030s, which will reduce travel times from 100 minutes to only 40. South Korea has experimented with smaller urban maglev lines, but Japan and China clearly dominate the field.

The technology behind maglev is rooted in magnetism. By harnessing electromagnetic forces, trains can float above their guideways, eliminating rolling resistance and delivering both speed and smoothness. Shanghai’s system uses electromagnetic suspension, in which magnets mounted beneath the train pull it upward toward a steel track. The gap between train and rail is a mere 15 millimeters, with sensors constantly adjusting to maintain stability, allowing the train to levitate even at a standstill. Japan’s SCMaglev takes a different approach, using superconducting magnets cooled to extremely low temperatures. At low speeds, wheels support the train, but once it surpasses 150 kilometers per hour, powerful repulsive forces lift it about 10 centimeters above the track. The guideway itself acts as a massive linear motor, propelling the train forward as if it were riding a wave.

The result is a ride so stable that during one famous demonstration in Japan, a coin placed on the floor of a moving maglev train remained standing upright at top speed. For passengers, the experience is unlike any traditional train: there is no clatter, no vibration, and no sense of friction. Acceleration feels smooth, curves are steady, and the only major force working against the train is air resistance.

The passenger benefits of maglev are undeniable, but the costs are daunting. With no wheels or axles, the trains require less maintenance than conventional rolling stock, but the infrastructure is another matter entirely. Maglev lines cannot run on existing tracks, meaning every new route requires the construction of a dedicated guideway, a massive financial hurdle that makes governments hesitate.

Asia’s lead comes from more than just technology. China made high-speed rail a national priority, investing hundreds of billions of dollars to expand its network. Japan, though slower, has spent decades steadily funding research and development, creating the world’s most advanced maglev project. Both countries benefit from densely populated megacities that generate the demand necessary to justify such costly projects. They also treat high-speed rail as a strategic industry, using it not only to move people but also to expand technological leadership and global influence.

By contrast, Western efforts often falter. In the United States, the California high-speed rail project has ballooned from an initial $33 billion estimate to over $128 billion, with only a partial Central Valley section under construction. A proposed maglev line between Washington, D.C., and Baltimore, which promised a 15-minute journey, was effectively shelved in 2025 after its environmental review stalled. Britain’s HS2, once hailed as Europe’s next big high-speed rail success, saw its costs triple and its northern section scrapped. Even Germany, birthplace of maglev technology, abandoned plans for a Munich airport connection in 2008.

Despite their futuristic promise, maglev trains are not without problems. The Shanghai line, though record-setting, cost over a billion dollars for just 30 kilometers and has never been expanded. Japan’s SCMaglev continues to face delays, with construction slowed by environmental concerns, particularly groundwater issues along its planned route. Even with political will, these projects are complex and enormously expensive. And because maglev requires brand-new infrastructure, it cannot benefit from the upgrades and retrofits that keep conventional high-speed rail relatively affordable.

Still, momentum in Asia shows no sign of slowing. China is already experimenting with vacuum tube maglev concepts that could break the 600-kilometer-per-hour barrier, while Japan is determined to extend its maglev line from Tokyo to Osaka. By the 2030s, passengers in Asia may routinely travel at jet-like speeds without leaving the ground.