MIT scientists have discovered a groundbreaking method to produce hydrogen fuel using everyday materials like soda cans, seawater, and coffee grounds. This chemical reaction could power engines or fuel cells in marine vehicles that draw in seawater.

Hydrogen is a vital component in the quest for cleaner energy due to its clean-burning properties and high energy density. When utilized in fuel cells, its only by-product is water. However, hydrogen storage and transport pose significant challenges as the small molecules tend to leak through containers and pipelines, leading to losses and potential atmospheric damage.

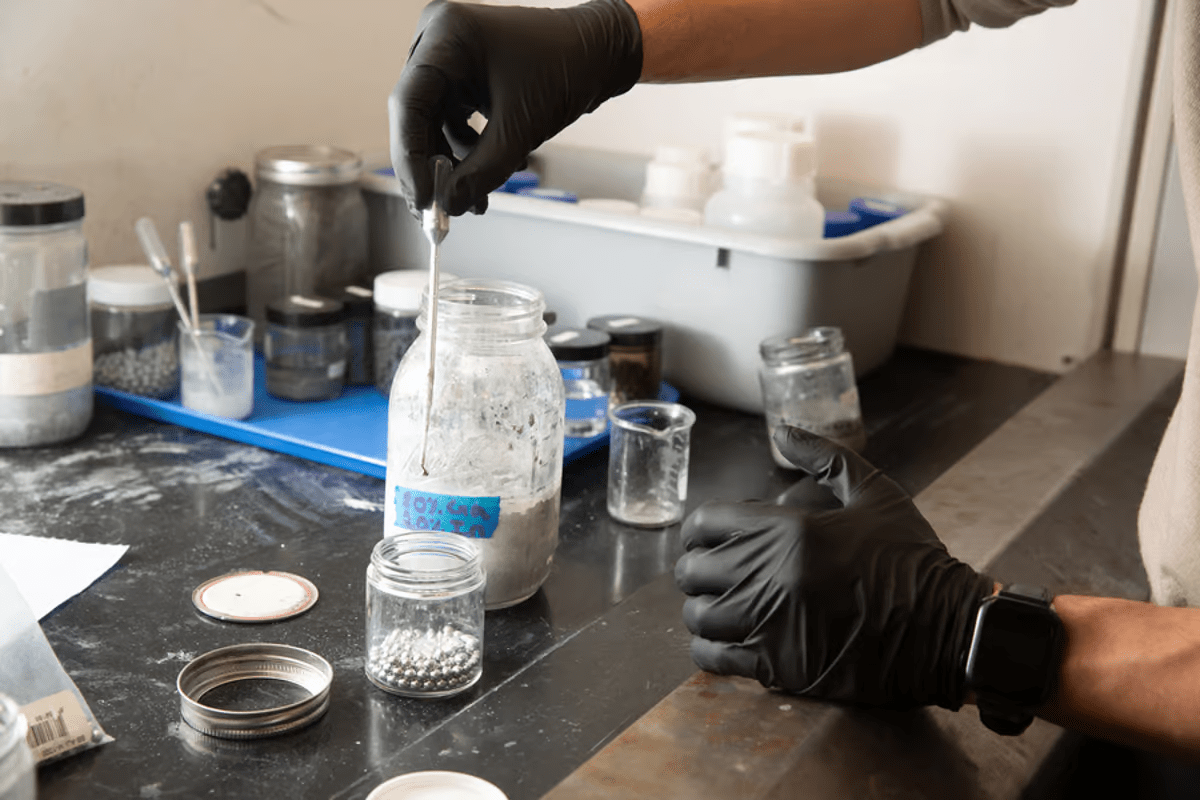

MIT’s new technique offers a solution by enabling hydrogen production on-demand directly within a vehicle. Instead of transporting volatile hydrogen, only stable aluminum pellets would need to be stored. In laboratory tests, a single 0.3-gram aluminum pellet in fresh, de-ionized water produced 400 milliliters of hydrogen in just five minutes. Scaling this up, one gram of aluminum pellets could generate 1.3 liters of hydrogen in the same time frame.

The process hinges on a straightforward chemical reaction: aluminum reacts aggressively with oxygen. When submerged in water, aluminum strips oxygen from H2O, releasing hydrogen gas. This reaction typically halts quickly as a layer of aluminum oxide forms on the metal’s surface, preventing further interaction. However, by pretreating the aluminum pellets with an alloy of gallium and indium, the MIT team was able to prolong the reaction by breaking down this oxide layer.

While gallium and indium are rare and costly, the researchers discovered that performing the reaction in an ionic solution, such as seawater, caused the alloy to clump together, allowing it to be easily recovered and reused. Initially, the reaction in seawater was slow, taking about two hours to produce the same amount of hydrogen achieved in five minutes with fresh water. Surprisingly, adding used coffee grounds to the mixture sped up the reaction significantly, returning it to the five-minute mark. The key component in coffee grounds, imidazole, a compound in caffeine, was identified as the catalyst.

Lead author Aly Kombargi highlighted the practicality of this method for maritime applications. “This is very interesting for maritime applications like boats or underwater vehicles because you wouldn’t have to carry around seawater – it’s readily available,” Kombardi explained. “We also don’t have to carry a tank of hydrogen. Instead, we would transport aluminum as the ‘fuel,’ and just add water to produce the hydrogen that we need.”

The team plans to test this concept on a small underwater glider, which, based on their calculations, could operate for up to 30 days by drawing seawater through a reactor containing about 40 pounds (18 kilograms) of aluminum pellets.

Kombargi envisions expanding this technology beyond marine vehicles. “We’re showing a new way to produce hydrogen fuel, without carrying hydrogen but carrying aluminum as the ‘fuel’,” he said. “The next part is to figure out how to use this for trucks, trains, and maybe airplanes. Perhaps, instead of having to carry water as well, we could extract water from the ambient humidity to produce hydrogen. That’s down the line.”

The research has been published in the journal Cell Reports Physical Science.

Here is a video demonstration of the reaction: