“Innovation happens when two disciplines of science that normally don’t intersect come together. If you’re a foot in both of those worlds, you’ll notice something obvious – that won’t come easily to the others,” Sonja Salmon, an associate professor of textile engineering, chemistry, and science at NC State, tells IE in an interview.

Salmon is referring to her expertise in textile engineering and biochemistry. Recently, Salmon and Jialong Shen, a postdoctoral research scholar at NC State, developed an apparently simple textile-based filter that can capture carbon dioxide emissions.

The researchers chose a piece of cotton cloth, known for its diverse properties, and a naturally occurring enzyme called carbonic anhydrase to create the fabric, whose special property is simply removing carbon dioxide molecules from a gas mixture.

Their findings were published in the journal ACS Sustainable Chemical Engineering earlier this month.

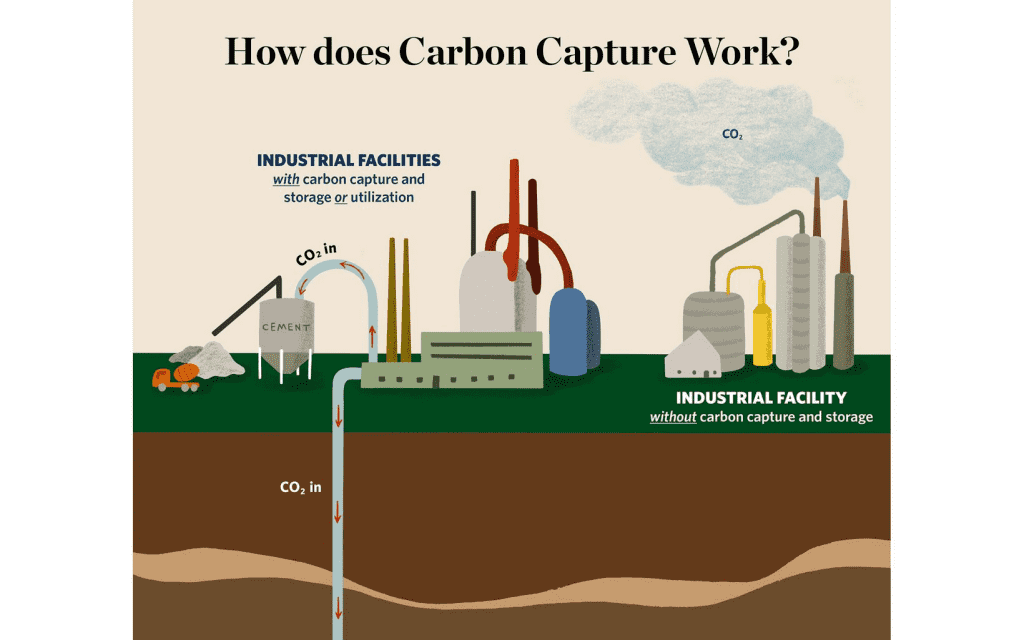

It is a known fact that carbon dioxide levels today are some of the highest that have been seen in the past 800,000 years. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the fossil fuels that people burn for energy are primarily responsible for the current high concentrations of CO2.

“I’ve been working in this field since 2005. At the time, global CO2 emissions were only 24 billion tons per year. Now they are greater than 35 billion tons per year. Humans crave energy, and we are throwing away the byproduct of that need for energy — which is carbon dioxide — away in the air and not collecting it. We can’t see or smell it. It’s very invisible to us, but it’s causing a very big problem for our planet, and we need to do something about that,” says Salmon.

“One thing that we already know about cotton is that it absorbs and transports water and moisture well,” she says.

Cotton can also be used to spread the water out into a thin film, creating a very high contact area for the gas. “When carbon dioxide gas molecules have to be removed from gas mixtures, the molecule has to come in contact with something – hence the big surface area,” explains Salmon.

According to the researchers, their “textile filters with enzyme attached work like a mix between an air filter and a water filter that carry out a chemical reaction at the same time.”

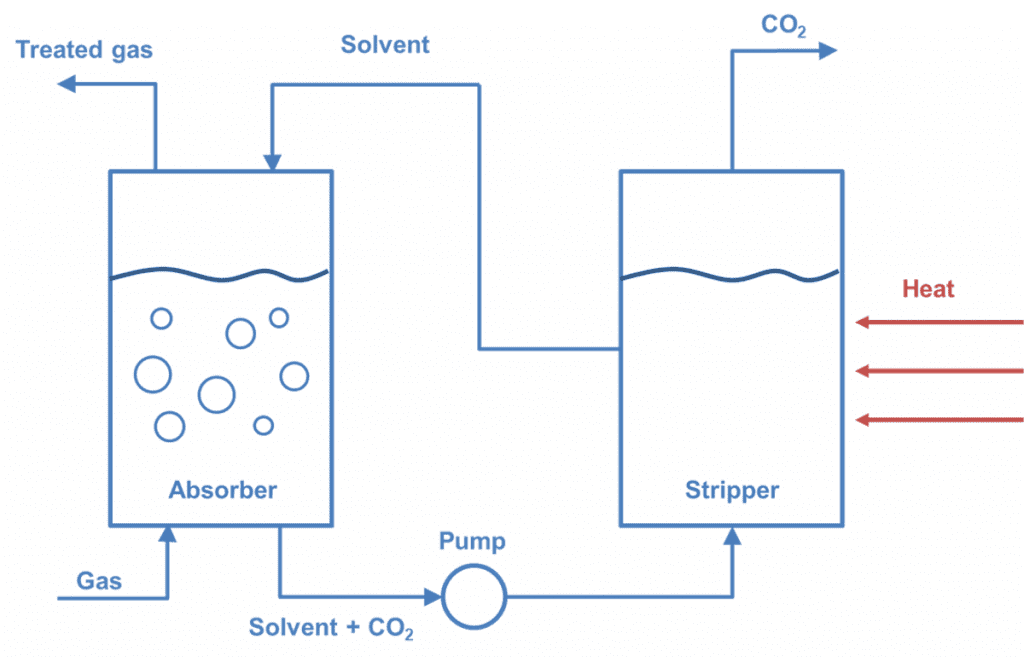

“There are conventional carbon capture systems working today that are used in the oil and gas industry – to purify methane, natural gas mostly. When natural gas is taken out of the ground, it’s often mixed with carbon dioxide. So, the technology for separating carbon dioxide from gases has already existed for decades,” explains Salmon.

“Our technology uses textiles and enzymes to capture the CO2 molecules in a very efficient manner,” says Salmon.

To create the filter, the enzyme was adhered to a piece of two-layer cotton fabric by ‘dunking’ the fabric in a solution containing chitosan, which acts like glue. The material traps the enzyme, which then sticks to the fabric, according to a press release.

“To tackle this huge problem [Carbon emissions], we were sure that the technology [the one they’re working on] should have to be scaled up very quickly,” Shen tells IE.

The researchers are already looking at real-world applications – power plants. “The problem with currently-used technologies is that it involves a lot of energy to regenerate the solvent, which is expensive,” says Shen. The team intends to use solvents with low regeneration energy, a “cost-effective method that can be deployed at scale.”

“Together with our collaborators, we have done some scale-up, and hopefully, there will be a publication later this year about that work. Frankly, we think the technology works well enough already to think about trying to deploy them on a larger scale. But that means having partnerships with commercial opportunities. We’re now starting to talk to folks about that and look forward to making progress,” says Salmon.

“There’s also the perception that we’ve been throwing CO2 away for free and now have to pay for it — that stands as an obstacle. But people need to understand that unless we pay for it our planet is in trouble,” adds Salmon.