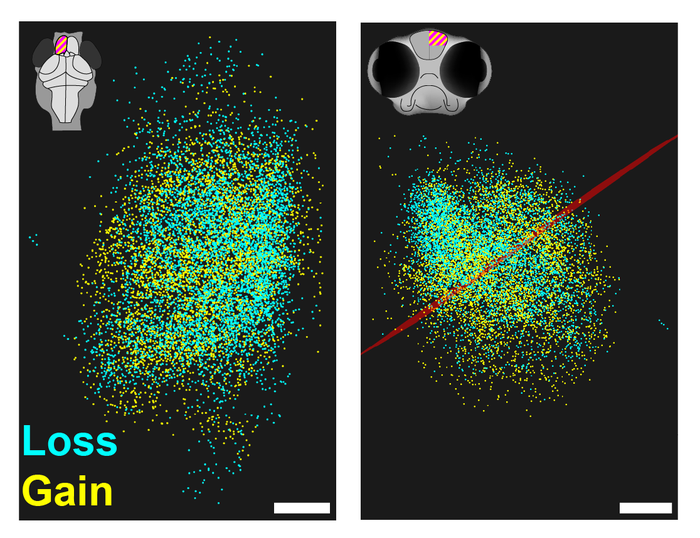

The formation of memories inside the brains of living fish was observed by scientists at the University of Southern California (USC). Furthermore, instead of strengthening, synapses grew in one part of the brain while vanishing in another.

Synapses are small spaces in the brain that connect the branches of nearby neurons, and they play a vital role in memory formation. When a synapse is used frequently, it develops more strongly, reinforcing a memory associated with that synapse. However, a recent study found that there is more to this theory.

Zebrafish, which are commonly employed in neurological studies, were used by USC researchers. Fish have brains that are similar to those of humans. However, they also have translucent skulls, allowing scientists to peer into the brain’s inner workings.

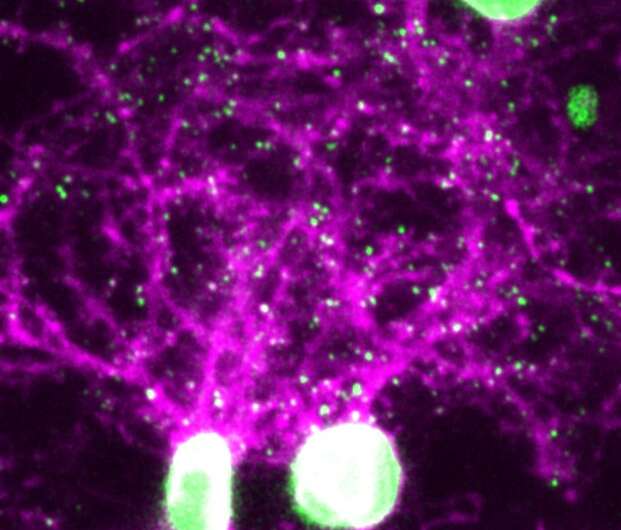

Synapses are too small to observe; therefore, researchers devised a few unique ways to detect them. First, they genetically engineered the fish to develop fluorescent synapses. Next, they analyzed them using a laser microscope that uses lower light to avoid tissue damage. The researchers utilised this setup to image the fish brains before and after establishing a memory to see how the synapses changed.

Furthermore, the researchers trained the fish with two stimuli, neutral and negative, to increase memory formation. Finally, an infrared laser heated the animals’ heads, which they found bothersome and floated away by fanning their tails. After a few hours, the fish began flicking their tails in response to the light, showing an associative memory development for the light and the heat.

The researchers were taken aback by the findings. One area of the brain was making new synapses, and another was removing them. According to the study, memory is encoded by varying the number of synapses.

“For the last 40 years, the common wisdom was that you learn by changing the strength of the synapses, but that’s not what we found in this case,” says Carl Kesselman, an author of the study.

More research is required to confirm the involvement of synapse growth and loss in memory formation. In addition, more study aims to eliminate synapses in zebrafish or mice to determine if associative memories are also erased, which could lead to novel treatments for PTSD, according to the researchers.

The study was published in the journal PNAS.