The pandemic has demonstrated that scientific knowledge still does not fully comprehend the complex immune system. However, thanks to a group of researchers at Harvard University’s Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering, scientists now have a new tool to help unravel the complexities of the immune system.

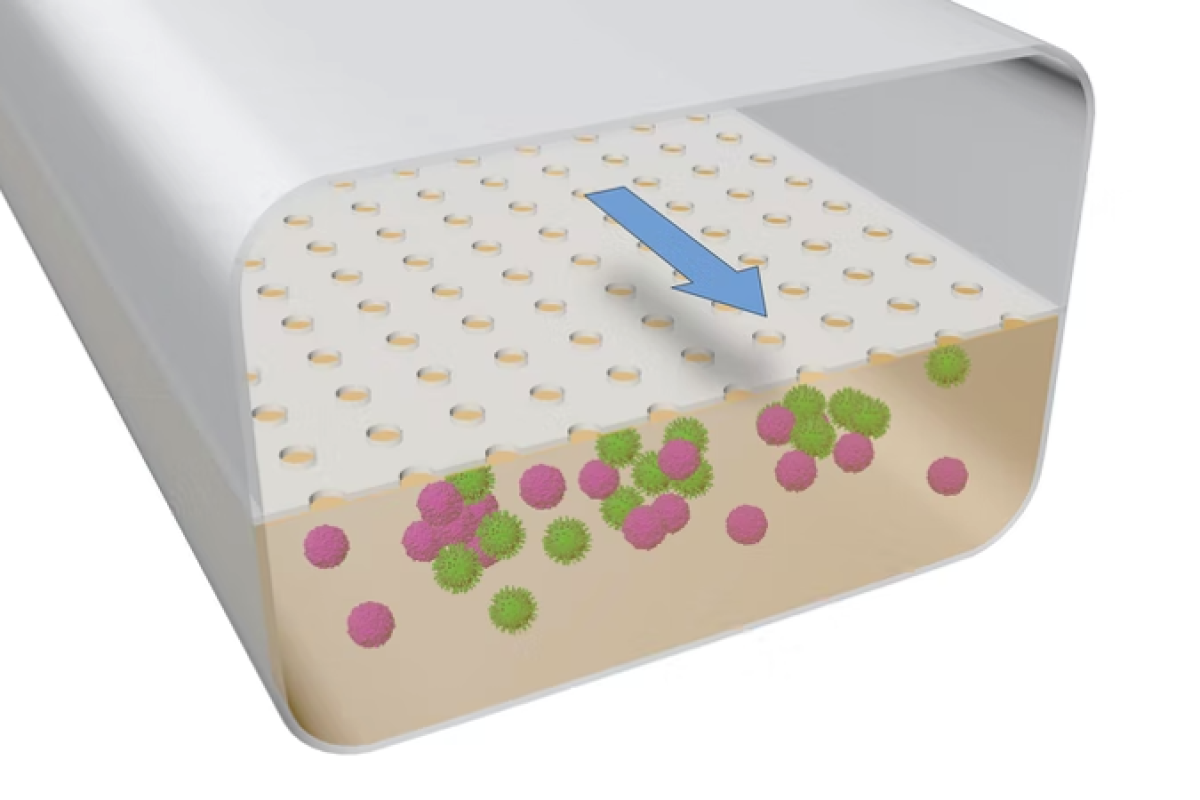

A microfluidic chip has been used to create a precise model of the human immune system, offering an excellent framework for researching how immune cells respond to vaccines and diseases.

During the study, scientists have developed a way for simulating organs and tissues on microfluidic chips rather than animals or lab chips. The researchers grew human B and T cells in a microfluidic system that mimicked the physical conditions these immune cells would face if they came into contact with an organ. As a result, the researchers were first concerned about those cells when they approached other organisms.

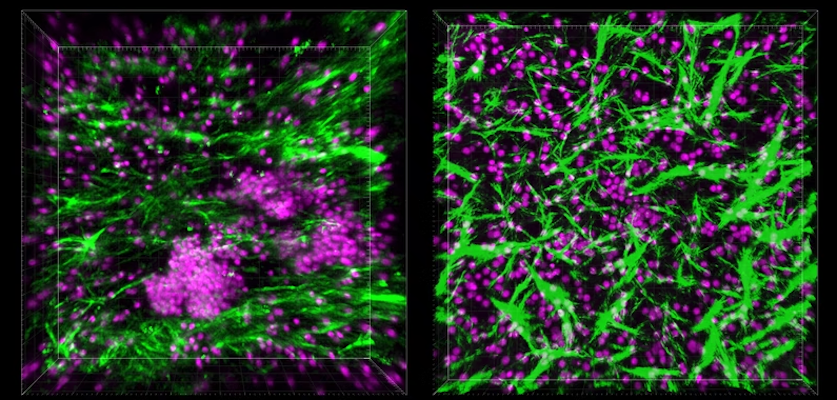

B and T cells created 3D structures that resembled lymphoid follicles (LFs). In addition, germinal centres, which perform complex immunological reactions, seemed to be generated by them.

When the researchers started probing the mysterious structures that had formed inside the Organ Chip under flow conditions, they found that the cells were secreting a chemical called CXCL13, which is a hallmark of LF formation, both within lymph nodes and in other parts of the body in response to chronic inflammation.

In addition, the team also found that B cells within the LFs that self-assembled on-chip also expressed an enzyme called activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID). Furthermore, scientists came across plasma cells formed when B cells release antibodies.

“These findings were especially exciting because they confirmed that we had a functional model that could be used to unravel some of the complexities of the human immune system, including its responses to multiple types of pathogens,” said Pranav Prabhala, co-author of the study.

Now that the scientists had a functional LF model that could initiate an immune response, they investigated whether their LF Chip could be used to research the human immune system’s reaction to vaccinations.

The researchers added dendritic cells to LF Chips along with B and T cells from four separate human donors. They then inoculated the chips with a vaccine against the H5N1 strain of influenza along with an adjuvant called SWE that is known to boost immune responses to the vaccine.

“Our LF Chip offers a way to model the complex choreography of human immune responses to infection and vaccination and could significantly speed up the pace and quality of vaccine creation in the future,” Goyal added.

LF Chips that received the vaccine and the adjuvant produced significantly more plasma cells and anti-influenza antibodies than B and T cells grown in 2D cultures or LF Chips that received the vaccine but not the adjuvant.

The experiment was subsequently performed with cells from eight different donors, using the commercially available Fluzone influenza vaccination, which protects against three distinct strains of the virus in humans. Plasma cells and anti-influenza antibodies were found in high concentrations in the treated LF Chips. They also evaluated the amounts of four cytokines in the vaccinated LF Chips. They discovered that three of them (IFN-, IL-10, and IL-2) were comparable to those reported in the serum of humans vaccinated with Fluzone.

“The flurry of vaccine development efforts sparked by the COVID-19 pandemic were impressive for their speed, but the increased demand suddenly made traditional animal models scarce resources. The LF Chip offers a cheaper, faster, and more predictive model for studying human immune responses to both infections and vaccines, and we hope it will streamline and improve vaccine development against many diseases in the future,” said corresponding author Donald Ingber, M.D., PhD.

In conjunction with pharmaceutical companies and the Gates Foundation, Wyss researchers are currently utilising their LF Chips to evaluate various vaccinations and adjuvants.

The research was published in the journal Advanced Science.

Source: Wyss Institute