The Zurich University of Applied Sciences (ZHAW) has a fully developed laboratory with scientific tools to stir a brown stack inside a plastic bag. At the same time, a buzzing sound plays in the background. Next to it is a glass pot in which more brown substance is being whipped.

“Here in the lab, we are actually just imitating processes that happen in nature,” says Regine Eibl, a teacher at the ZHAW institute of technology in Wädenswil. Prof. Eibl, the head of the Cell Culture Technology department, is the main guy behind the lab-grown chocolate.

Eibl’s team originally grows cell cultures for the pharmaceutical industry and initially didn’t intend to establish a cell culture to make chocolate.

“The idea came from a colleague of mine, Tilo Hühn,” she recalls. “He asked me if we could try to extract plant-based cell cultures from cocoa beans. We wanted to see if these cell cultures would produce polyphenols, which happen to be very important for the perception and sensory effects of chocolate.”

Hühn is a name known to many; quite a few projects even caught the headlines, including a chocolate product elaborated with the entrepreneur and pop singer Dieter Meier (singer of Yello). The product somewhat has a strong chocolate aroma compared to a bar of traditional chocolate.

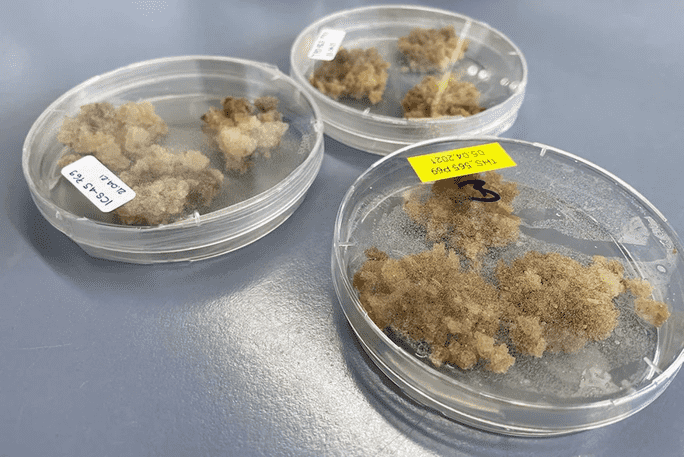

However, lab-grown chocolate is still Hühn’s most impressive project to date. The process starts with surface cleansing of the cocoa fruit; the cocoa beans are initially extracted in a sterile process, then sliced up with a scalpel and nurtured on a culture medium at 29°C without light.

Around three weeks, a rough scab known as callus grows on the cut surfaces. “It is done in a very simple culture medium”, says Eibl.

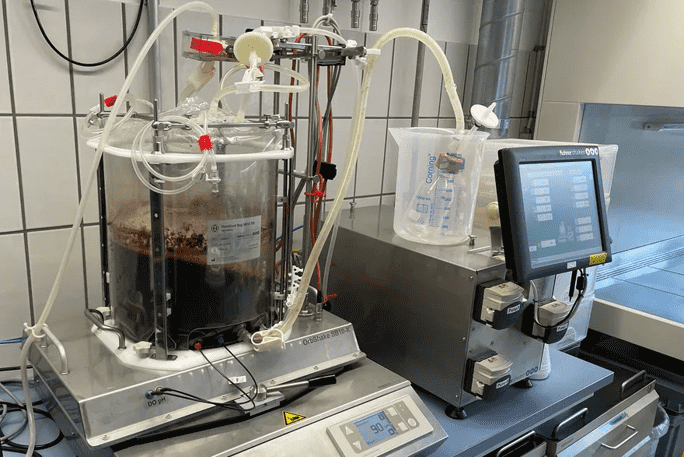

Next, the material is transferred into quaking flasks, and suspension culture is added, and it is grown in a bioreactor. “Reactor is a terrible word. It’s really just a tank, like the kind you ferment wine in”, says Hühn.

Lastly, the cell culture enables you to make as much chocolate as required. It can be seen as a kefir fungus or sourdough starter from which you can take a smidgen whenever required. The food industry is currently fascinated by these cell cultures, notes Eibl.

“We want to see what the future of foodstuffs out of a tank might look like. Mind you, a complete de-territorialisation, getting away from the earth completely, is not what we’re after; the main idea, he says, is “creating conditions that don’t take up so much of the environment and leave a very light footprint when we make these products” explains Hühn.

Increased demand for chocolate seems to create an issue for the supply chain. Massive production could have a major impact on easing supply chains worldwide. “There are also really unacceptable situations involving child labour in several of the producing regions. The way we are going here could lead to a number of problems being solved,” says Hühn.

However, Chocosuisse, Switzerland’s chocolate industry association, has been silent on the issue.

Typically, lab-grown chocolate tastes like traditional chocolate. The only difference lies in its fruity flavour, which instantly strikes change. Researchers Irene Chetschik and Karin Chatelain are responsible for detecting the flavours present in the different kinds of chocolate. Over the past few weeks, they have cracked the scent DNA of chocolate or cocoa and developed a kit similar to oenology with 25 different scents such as flowery, fruity, spicy or earthy. The kits are similar to those used in

Isn’t it ironic that there are no actual components present in chocolate that smells like cocoa? “The cocoa aroma is a combination of various chemical molecules with different-smelling qualities,” says Chetschik.

For now, this lab-grown chocolate is costly than the traditional one. According to Hühn, a hundred grammes of traditional organic chocolate costs CHF2.70 ($2.90) against CHF15 to 20, which is the price of Wädenswil product. Mass production, however, would lower the cost.

Compared with processes for producing meat in a laboratory, this approach is “definitely cheaper, and has less impact on the environment.

Huhn says, however, that our lab-grown food will not be a substitute for conventional agriculture. “We will not be making traditional production of cocoa beans obsolete, nor would we want to,” He adds.

For now, the researchers are only focused on comparing the production process between lab-grown and traditional chocolate.