Banana is considered to be one of the healthiest and most energetic fruits out there. From children to grandpas, it is liked by men and women of every age. It is a no brainer staple grocery item to buy when shopping for groceries; but this love story between us and the banana might be coming to an abrupt and unfortunate ending. An evolving fungal disease has been spreading like wildfire is now threatening to wipe out the fruit within the next decade.

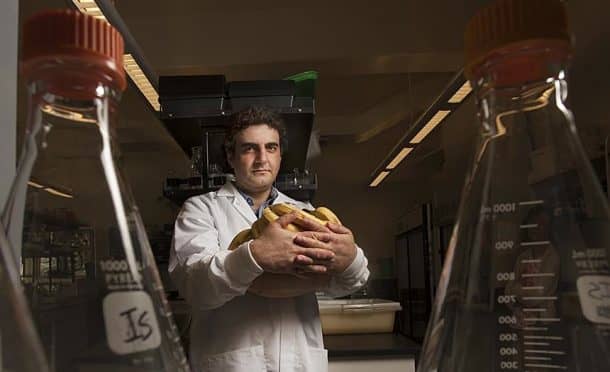

Researchers at University of California, Davis (UC Davis) have been warning about this impending doom for quite some time, and since then they have successfully planned out the genomes of the fungi to determine how it attacks its hosts in a bid to save the fruit from extinction. The reason why the fungal disease called Sigatoka is really getting a foothold is the kind of reproduction done by the banana plant. They usually consist of Cavendish type, which employs vegetative reproduction. Vegetative reproduction – as opposed to asexual reproduction – proceeds by cutting of the plant’s shoots and replanting them rather than growing from different seeds. This makes all the Cavendish bananas essentially “clones” of one plant having the same genotype, thus making all of them susceptible to the disease.

This fungal disease is comprised of three strains called yellow Sigatoka, black Sigatoka and eumusae leaf spot. The farmers are required to apply the expensive and environmentally dangerous fungicide to their crops 50 times a year in order to stop the fungus, which makes this a very hazardous, costly and labor intensive practice.

The spread of this fungus has been such that out of the 120 banana producing countries churning up about 100 million tons of bananas per annum, about 40 percent is spoiled; costing millions of dollars to the banana industry. This costly practice weighs in about 30 to 35 percent towards the banana production cost. And since most of the farmers can’t afford this kind of money, they have to settle on growing bananas of lesser quality bringing them lesser income.

Previously another popular species called the Gros Michel was wiped out by a similar fungus called Panama disease, giving rise to the Cavendish variety in the second half of the 20th century.

Researchers firstly found the cure of yellow Sigatoka, and after that sequenced for the other two diseases. They concluded from their observational results that the fungi not only shuts down the host plant’s immune system, but releases enzymes that break down the cell walls and feeds on the sugars and carbohydrates of the plant.

This conclusion is a big deal as the team hopes this will help them in reaching a solution that is less costly and more permanent.

They also revealed that the pathogen changes its metabolism to that of its host plant, and this may represent a ‘molecular fingerprint’ of the adaption process that needs to be researched upon in other plants with similar fungal problems.

Have anything else to add to this article? Comment below!