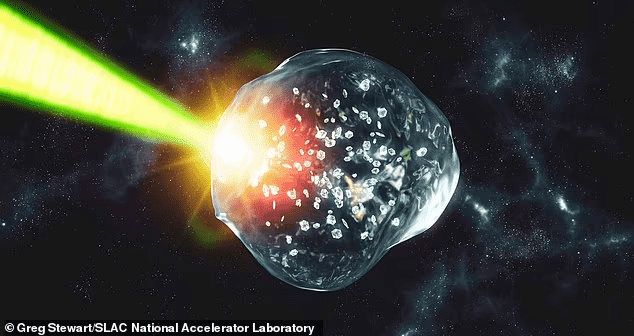

Have you ever heard of making diamonds out of plastic bottles? Probably not. Researchers from the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California created the phenomenon of “diamond rain” that usually occurs on Neptune and Uranus. The end product, however, has a lot of practical applications, specifically in the fields of medical sensors and drug delivery. Not only that, but this recycling process would also help in restricting plastic waste, which is unquestionably destroying our Earth’s atmosphere in one way or the other. For this, the researchers incorporated the use of an intense beam of laser on polyethylene terephthalate (PET) plastic and generated diamonds as an end product.

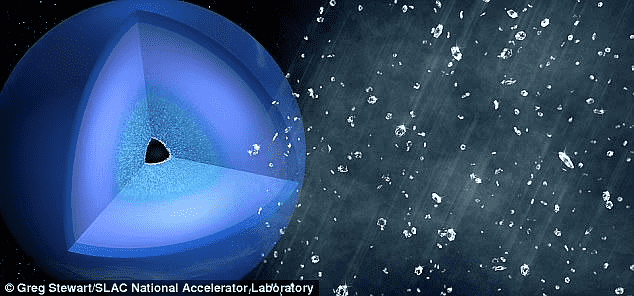

What actually happens in this diamond rain is that these rain droplets contain a temperature of around several thousand degrees and a pressure that is a million times greater than the Earth’s atmosphere. So, when the high-powered laser was fired on PET plastic, it generated diamond-like structures. As Dominik Kraus, who is a physicist at HZDR and professor at the University of Rostock, said, “PET has a good balance between carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen to simulate the activity of ice planets.” However, it has to be noted that these hydrocarbons are located about 5,000 miles under the surface of Uranus and Neptune.

The SLAC scientists first depicted this process in 2017 but with “polystyrene” which also contains hydrogen and carbon. The carbon atoms were transformed into small diamond-like structures when the X-rays were impacted on the material. According to Siegfried Glenzer, director of the High Energy Density Division at SLAC, “But inside planets, it’s much more complicated. There are a lot more chemicals in the mix. And so, what we wanted to figure out here was what sort of effect these additional chemicals have.” Hence, they performed the same experiment with PET plastic then, and fortunately, it depicted more accurate results.

A high-powered optical laser was used to heat the sample up to 10,800 °F (6,000 °C) at SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source. The mechanism, however, is used as the “X-ray diffraction technique.” Considering this, Dr. Kraus said, “The effect of the oxygen was to accelerate the splitting of the carbon and hydrogen and thus encourage the formation of nanodiamonds. It meant the carbon atoms could combine more easily and form diamonds.” Moreover, the findings of this study have been published in Science Advances. Apart from this, researchers now want to perform the same experiment using ethanol, water, and ammonia because of their presence on Uranus and Neptune. As they think, they might explore more details by going through different dimensions.

As per SLAC scientist and collaborator Benjamin Ofori-Okai, “The way nanodiamonds are currently made is by taking a bunch of carbon or diamond and blowing it up with explosives. This creates nanodiamonds of various sizes and shapes and is hard to control. What we’re seeing in this experiment is a different reactivity of the same species under high temperature and pressure. In some cases, the diamonds seem to be forming faster than others, which suggests that the presence of these other chemicals can speed up this process.”