Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have come up with a new theory to explain how oxygen concentration might have built up in the Earth’s atmosphere.

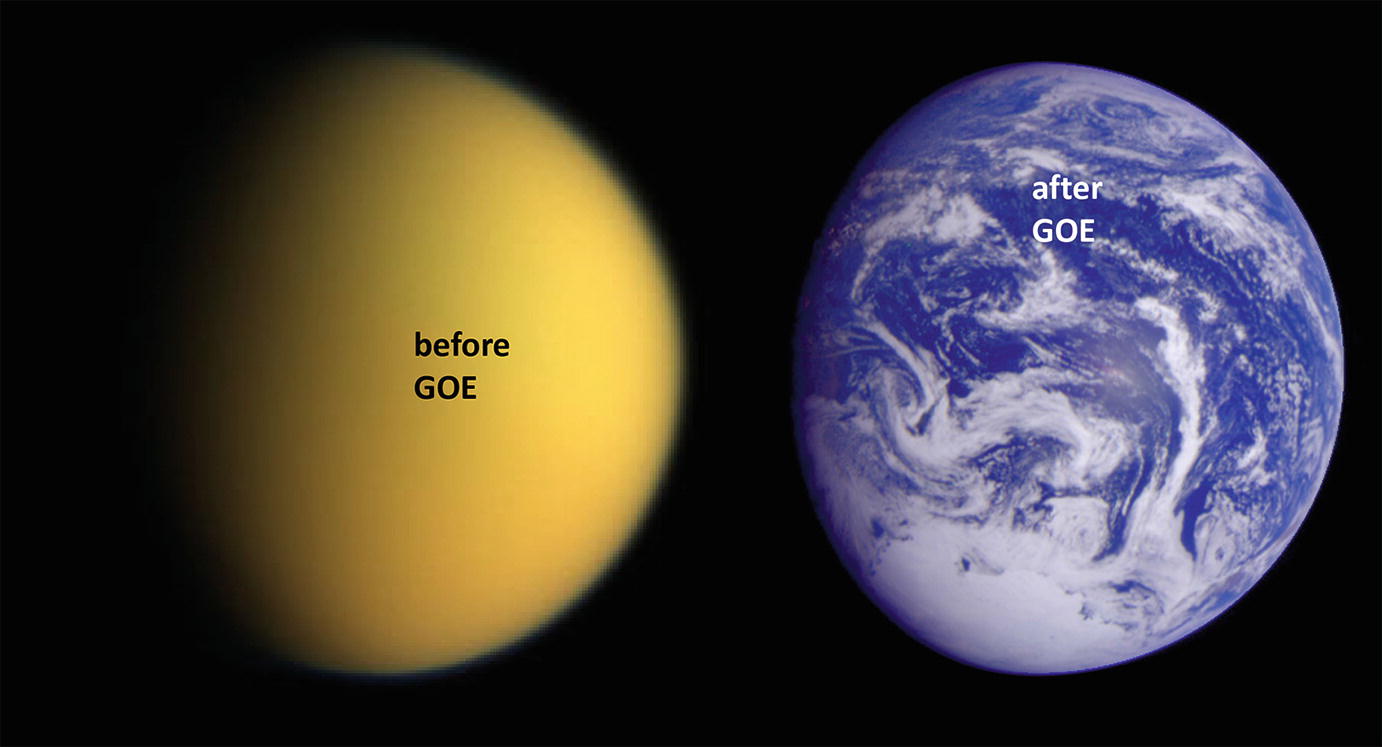

Some microbial organisms were thought to be using photosynthesis to generate some oxygen on earth as the planet was lacking in it. However, the amounts produced were not sufficient to support many lifeforms. With a couple of billion years, oxygen levels escalated, and the reason is unknown.

There were two events in the Paleoproterozoic period and the Neoproterozoic period, which saw oxygen levels go from low levels to much higher levels than the Earth has today.

Gregory Fournier, Associate Professor of Geobiology at the Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences (EAPS) at MIT, and his colleagues believe that these increases in oxygen levels weren’t the result of gradual change. Instead, there was a positive feedback loop that was activated in the oceans.

They hypothesized that if microbes in these environments could oxidize organic matter partially, the partially oxidized organic matter (POOM) would bind to the minerals to prevent their further oxidation. The oxygen unused in the process would be left in the atmosphere.

To verify their hypothesis, the researchers read through the scientific literature to identify microorganisms that could create POOM and found a bacterial group called SAR202 that can achieve the feat using an enzyme called Baeyer-Villiger monooxygenase, or simply BVMO.

Tracing back the genetic origins of this enzyme, the researchers found that the bacteria’s ancestors were indeed present prior to the GOE. Interestingly, the gene was acquired by multiple bacterial species during the Paleoproterozoic as well as Neoproterozoic, times when oxygen levels have been known to spike.

The mystery of the GOE may be heading towards a reveal.

Details of the theory can be found in the journal Nature Communications.