Last October, a collaboration called The Dickens Code project made a public appeal to amateur puzzle fans and codebreakers for help in decoding a letter written by Victorian novelist Charles Dickens. Shane Baggs, a computer technical support specialist from San Jose, California, won the overall contest, while a college student at the University of Virginia named Ken Cox was declared the runner-up.

The Dickens Code project is the result of a collaboration between Claire Wood of the University of Leicester, and Hugo Bowles of the University of Foggia. “Dickens’s shorthand has proved extremely difficult to decode,” they wrote on the project’s website. For those seeking to crack the code, it helps to identify the original source material, although “in most cases, experts have been unable to locate the source texts used for the exercises,” they wrote. “They could be published, or unpublished passages were written by Dickens, or by another author.”

There was another story that needed meaning. However, it had the second page missing and nobody knew how it ended. There is even a possibility that there might not have been a second page. The following page consists of a seemingly unrelated courtroom speech. “We won’t know if the story continues until we have had a closer look at the sequencing in the notebooks and transcribed more of the pages,” Wood and Bowles wrote.

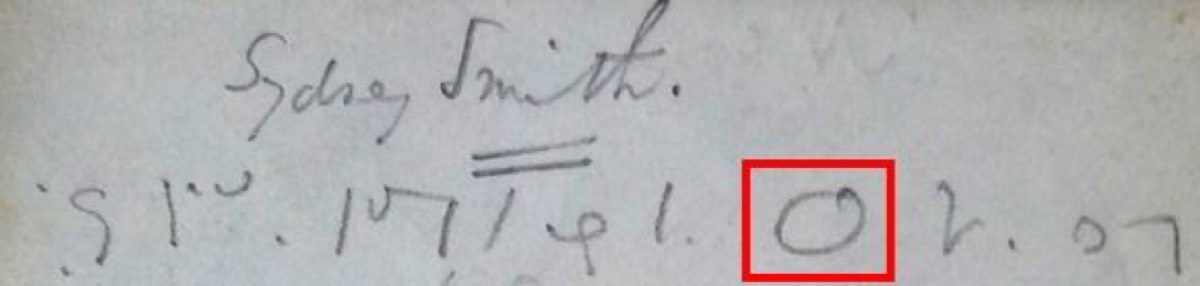

The contents of the Tavistock letter had not been deciphered until now. The Dickens Code project’s competition closed on New Year’s Eve, with sixteen formal submissions, none of which were complete. The judging panel decided the winners based on both the quality of the transcription and the quality of the accompanying report for each submission. In the end, Baggs and Cox managed to decipher the most symbols, although it was still very much a combined effort. The full line-by-line transcription, now about 70 percent complete.

“On compiling these solutions, the puzzle pieces started to fit together: a word here, or a key phrase there, that enabled us to pin down the timeframe and understand the context,” Wood and Bowles wrote. Three translations proved especially critical.

“HW” was a reference to Household Words, a periodical Dickens edited and co-owned with a publisher called Bradbury and Evans (B&E). Another entry linked the symbol for “round” with a new journal Dickens had founded in 1859, All the Year Round after he had a falling out with B&E. And two symbols translated into “Ascension Day,” which helped pinpoint the likely time in which the Tavistock letter had been written: 40 days after Easter in 1859.

It was found out that the letter was meant for J.T. Delane, editor of The Times, in May 1859, a personal acquaintance of the author, concerning a rejected advertisement for Dickens’ new magazine. According to them, Dickens was financially challenged at the time. He was divorcing his wife. And he had fallen out with B&E because the publisher had refused to publish Dickens’ furious denial of his extramarital affair with an actress in Punch. B&E didn’t accept Dickens’ offer to buy its share of Household Words, a major source of the author’s income at the time.

That’s why Dickens started All the Year Round. B&E sued to keep Dickens from telling people that Household Words was being discontinued.

There is another known letter, written in longhand, from The Times manager, apologizing to Dickens and reinstating the rejected advertisement. It is thought that it might be a response to the Tavistock letter. Afterward, All the Year Round was published.

“Thanks to the work of the Dickens decoders, we have gained new insight into this particularly fraught time in Dickens’s publishing career,” Wood and Bowles concluded. “Rather than Dickens the author, we see Dickens the businessman, involved in the minutiae of ensuring his new journal’s success and appealing to powerful friends to get the outcome that he desired.”