Not all parts of our planet face the same risk of being struck by an object from beyond the Solar System. A new study has found that certain regions of Earth are more exposed to potential impacts from interstellar visitors – objects that travel through space from other star systems. The research, detailed by ScienceAlert, explores how and where such cosmic collisions are most likely to occur.

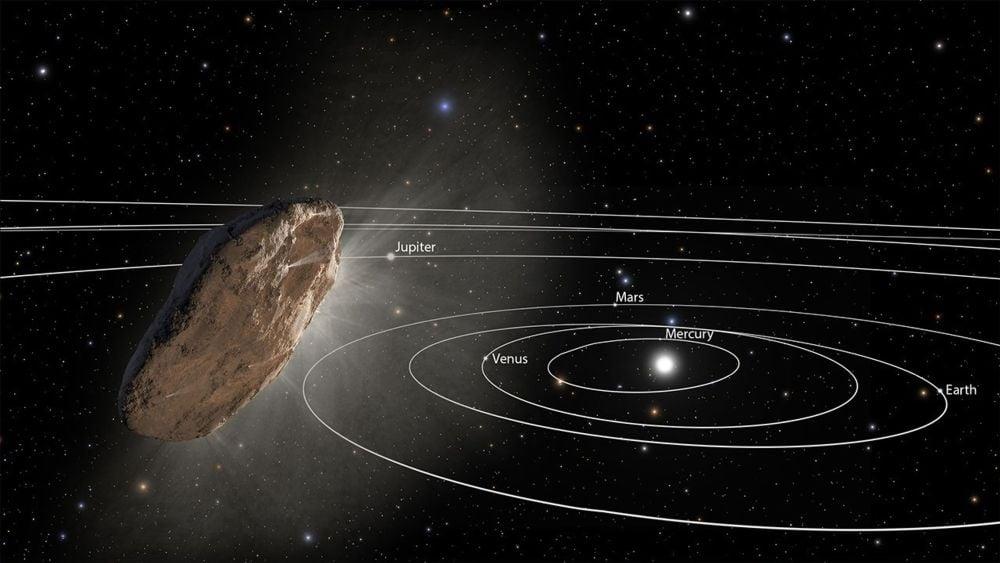

Scientists have confirmed only three interstellar objects (ISOs) so far: Oumuamua in 2017, 2I/Borisov in 2019, and the currently passing comet 3I/Atlas. These rare travelers entered the inner Solar System from deep space, offering brief but fascinating glimpses of material formed around distant stars. While none have come close to hitting Earth, the study suggests that over billions of years, many ISOs may have crossed paths with our planet – and possibly even caused ancient impact craters that still mark Earth’s surface today.

The new research, titled The Distribution of Earth-Impacting Interstellar Objects, was led by Darryl Seligman of Michigan State University. Using advanced simulations, the team modeled about 10 billion interstellar objects, generating roughly 10,000 virtual Earth impacts. The goal was not to predict when or how often impacts might happen, but to understand where they are most likely to come from and what parts of the planet are more vulnerable.

This artist’s illustration shows the interstellar object (ISO) Oumuamua travelling through our Solar System (NASA/ESA/J. Olmsted/F. Summers/STScI)

The study found that ISOs are twice as likely to approach Earth from two main directions: the solar apex and the galactic plane. The solar apex is the direction the Sun travels through the Milky Way, meaning Earth effectively faces a “headwind” of incoming debris as it moves through space. The galactic plane, on the other hand, is the dense disk-shaped region of the galaxy that contains most of its stars, making it another hotspot for potential interstellar arrivals.

When it comes to impact zones, low-latitude regions near the equator are most at risk, followed by a slightly higher chance in the Northern Hemisphere. This bias likely reflects Earth’s tilt, rotation, and the uneven distribution of land and population across hemispheres. The research also found that faster ISOs are more likely to strike during spring, when Earth’s orbit carries it toward the solar apex.

Although these results do not estimate how often an interstellar object might strike, they provide valuable guidance for future sky surveys, including the upcoming Vera Rubin Observatory. By understanding where and when such impacts are most likely, astronomers can better prepare to detect – or perhaps one day deflect – the next cosmic visitor from beyond our Solar System.