An ecologist from Utah State University has come up with a bleak possibility of one of the world’s largest living things, a colony of genetically identical trees sharing a single root system, breaking up into multiple distinct parts, for the first time in history.

Dubbed Pando, this unique colony of aspen trees was first discovered in the mid-1970s. Genetic testing revealed that each tree in the 100-acre (40.5-ha) colony was a clone of one another. This means they had a single gigantic underground root system.

Pando’s scale and age make it one of the most unique organisms on the planet. Pando’s overall root system has been estimated to be around 10,000 years old.

Pando is widely regarded as the world’s largest living organism in terms of gross biomass. Its weight is around 6,000 metric tons.

In 2017, ecologist, Paul Rogers co-authored a study that worked on finding the effects of modern forest management processes on the organism.

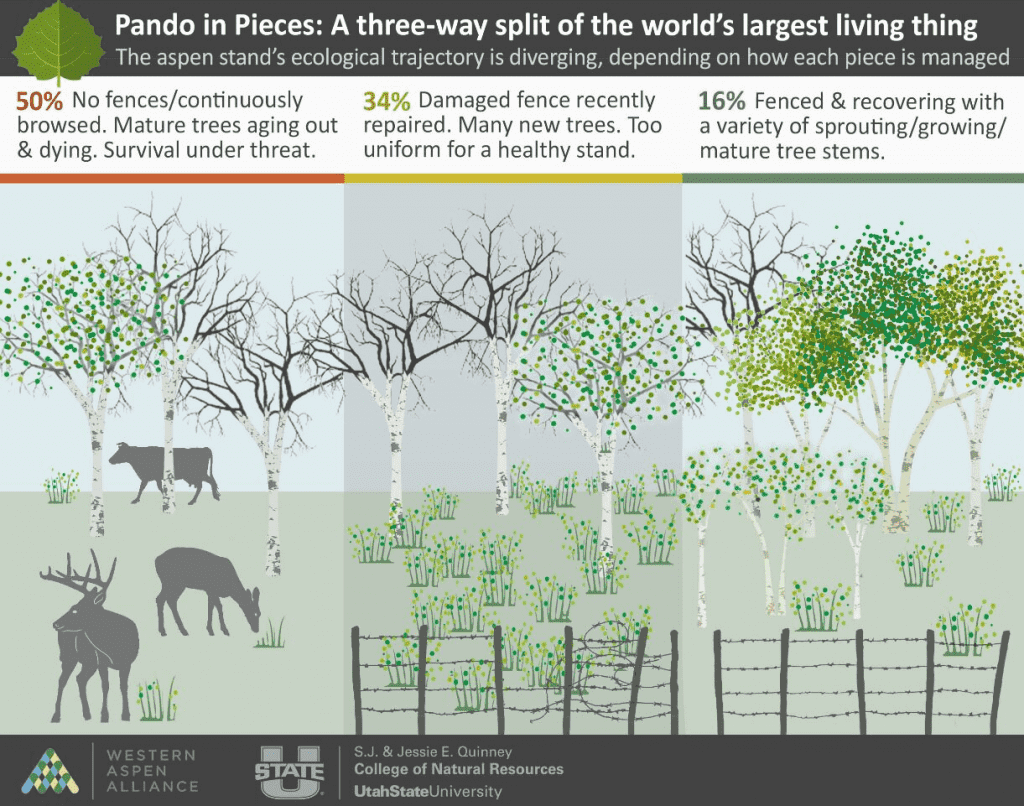

A study in 2018 revealed that protecting the areas around the tree and limiting access can help Pando to regenerate. However, in a new article Rogers is suggesting fencing may not be enough to save Pando as the massive root system is showing signs of breaking up into three distinct smaller bodies.

The main reason why this is happening is that deer and cattle eat new stems before they can grow. Originally, this happened because humans over the past century had reduced predator populations of wolves and bears in the area.

“I think that if we try to save the organism with fences alone, we’ll find ourselves trying to create something like a zoo in the wild,” explained Rogers. “Although the fencing strategy is well-intentioned, we’ll ultimately need to address the underlying problems of too many browsing deer and cattle on this landscape.”

“Pando is paradoxical: putatively earth’s largest organism, it is small as conservation challenges go,” writes Rogers in a new study. “Lessons from Pando may be applied to struggling, often species-rich, aspen systems facing similar challenges globally.”

The study was published in Conservation Science and Practice.