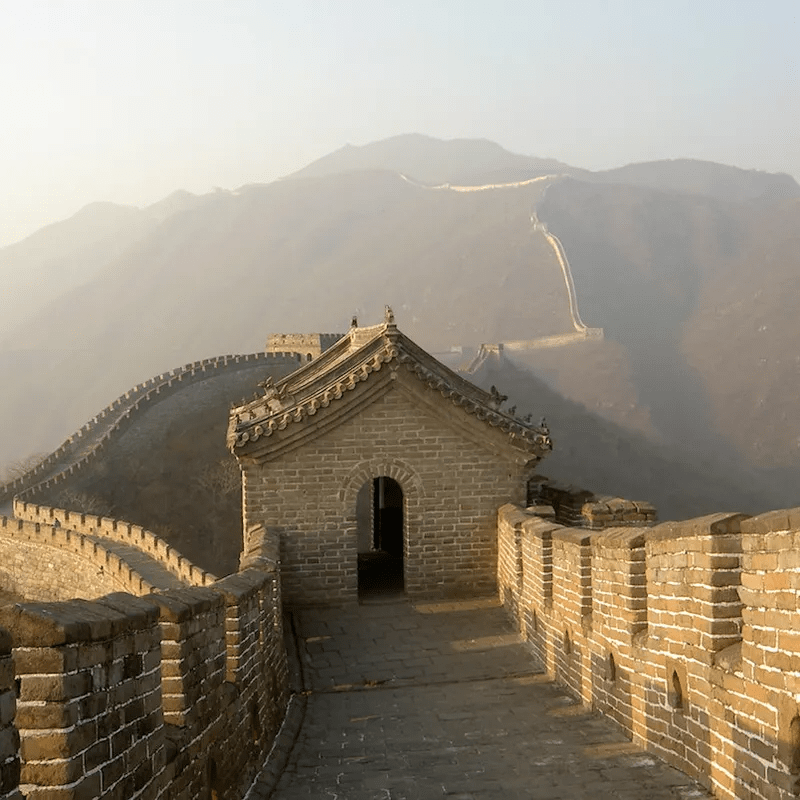

The majesty of the Great Wall of China, a testament to ancient engineering, faces the relentless erosion of time. What stands today is but a fraction of its former glory, yet an unexpected ally may be contributing to its preservation: the unassuming “living skins” of bacteria, moss, lichen, and other organisms known as biocrusts.

A recent study in Science Advances sheds light on how these living layers protect sections of the Great Wall from the erosive forces of wind, rain, and time, challenging conventional notions of heritage conservation.

Many renowned sections of the Great Wall are constructed from stone or brick, while others utilize compacted soil, vulnerable to degradation from rain, wind, salt, and temperature fluctuations. Enter biocrusts, these living coatings covering about 12% of the Earth’s land surface, which may be the key to safeguarding this cultural treasure.

Soil scientist Bo Xiao and his team at China Agricultural University explored the role of biocrusts in stabilizing human-made structures like the Great Wall. Biocrusts, predominantly composed of moss or cyanobacteria, covered over two-thirds of the sections studied. Comparisons between biocrust-covered and bare sections revealed that biocrusts enhanced the structural integrity of rammed Earth, making it less porous with higher shear and compressive strength.

These properties, linked to biocrusts, shield the Great Wall by reducing wind erosion, preventing water and salt infiltration, and bolstering overall stability. The study challenges conventional heritage conservation beliefs, dispelling fears that plant growth, often associated with damage through root systems, would be detrimental.

However, biocrusts face threats from climate change and intensive land use, putting their protective benefits at risk. As the climate warms along the Great Wall, moss-dominated crusts may yield thinner cyanobacterial crusts, requiring less water.

Recent global research explores the restoration of damaged biocrusts, although efforts remain in the research and development stage. Intentional growth of biocrusts along more minor features, such as the Great Wall, is deemed more feasible than large-scale restoration.

Recognizing the Great Wall as a cultural symbol, efforts to ensure its standing for future generations become crucial, echoing the sentiment that preserving the past involves embracing the present innovations.