Astronomers have made an astonishing detection in Venus’ cloud tops: a gas called phosphine that on Earth is created through biological processes.

NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) selected three new missions to travel to the planet and investigate. China and India also plan to send missions to Venus. “Phosphine reminded everybody how poorly characterized [this planet] was,” says Colin Wilson at the University of Oxford, one of the deputies lead scientists on Europe’s Venus mission, EnVision.

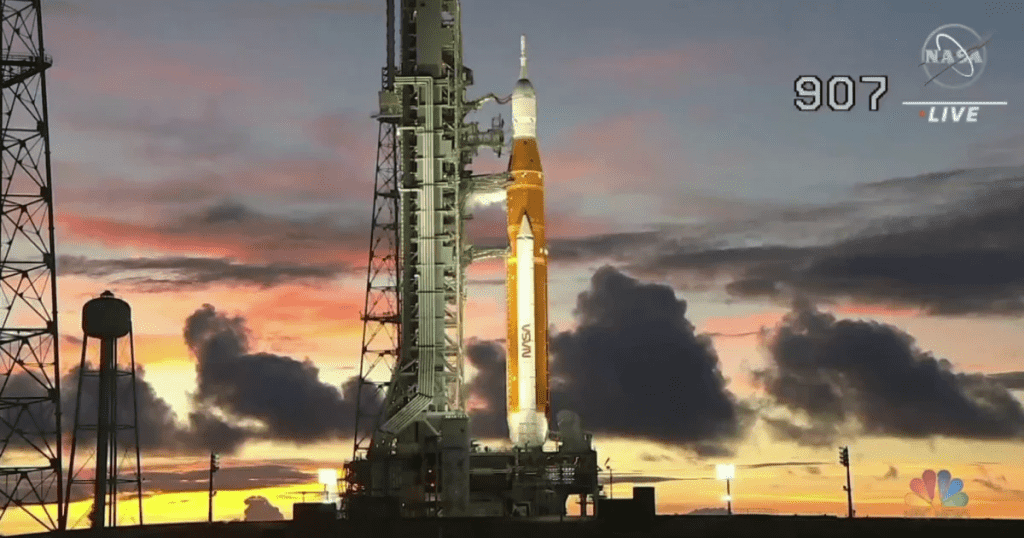

Peter Beck, the CEO of the New Zealand–based launch company Rocket Lab got some insight before others. Beck was contacted by a group of MIT scientists about a bold mission that could use one of the company’s rockets to hunt for life on Venus much sooner—with a launch in 2023.

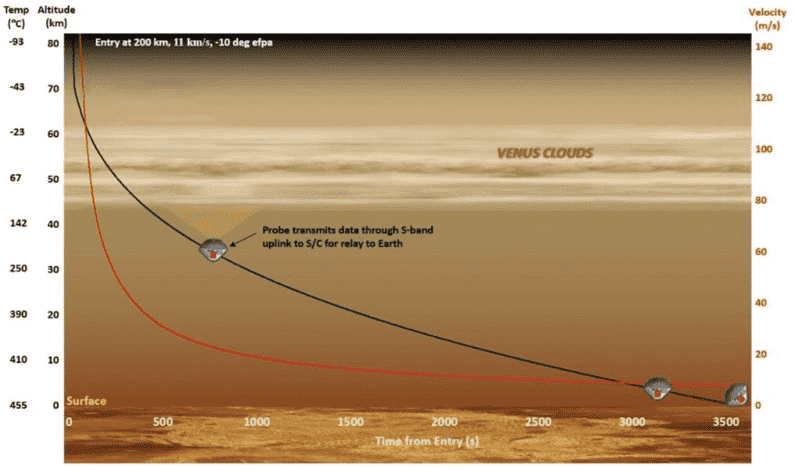

Scientists believe that life on Venus is in the form of microbes inside tiny droplets of sulfuric acid that float high above the planet. The surface appears largely inhospitable, with temperatures hot enough to melt lead and pressures like those at the bottom of Earth’s oceans, conditions about 45 to 60 kilometers above the ground in the clouds of Venus are significantly more temperate.

“I’ve always felt that Venus has got a hard rap,” says Beck. “The discovery of phosphine was the catalyst. We need to go to Venus to look for life.”

That probe is being developed by a team of fewer than 30 people, led by Sara Seager at MIT at the moment. Launching as soon as May 2023, it should take five months to reach Venus, arriving in October 2023. The budget of the mission is $10 million and is funded by Rocket Lab, MIT, and anonymous philanthropists. It is high risk but low cost, just 2% of the price for each of NASA’s Venus missions.

“This is the simplest, cheapest, and best thing you could do to try and make a great discovery,” says Seager.

The probe is small, 45 pounds, and measures 15 inches across. Its cone-shaped design has a heat shield at the front, which will tolerate the heat encounters.

Inside the probe will be a single instrument weighing only two pounds. “We have to be very, very frugal with the data that we’re sending back,” says Beck.

“We’re going to look for organic particles inside the cloud droplets,” Seager says. Such a discovery wouldn’t be proof of life—organic molecules can be created in ways that have nothing to do with biological processes. But if they were found, it would be a step “toward us considering Venus as a potentially habitable environment,” says Seager.

The mission will not look for phosphine itself because a suitable instrument for that would not fit in the probe, Seager says. But that could be covered by NASA’s DAVINCI+ mission, set to launch in 2029.

The probe will have just five minutes in the clouds of Venus to perform its experiment, radioing its data back to Earth as it plummets towards the surface.

Jane Greaves, who led the initial study of phosphine on Venus, says she is looking forward to the mission. “I’m very excited about it,” she says, adding that it has a “great chance” at detecting organic materials, which “might mean life is there.”

“We need more time in the clouds,” says Seager—ideally with something larger that has more instruments on board. “An hour would be enough to search for complex molecules, not just see their imprint.”

Could this small but mighty effort be the first to find evidence of alien life in the universe? “The chances are low,” says Beck. “But it’s worth a try.”