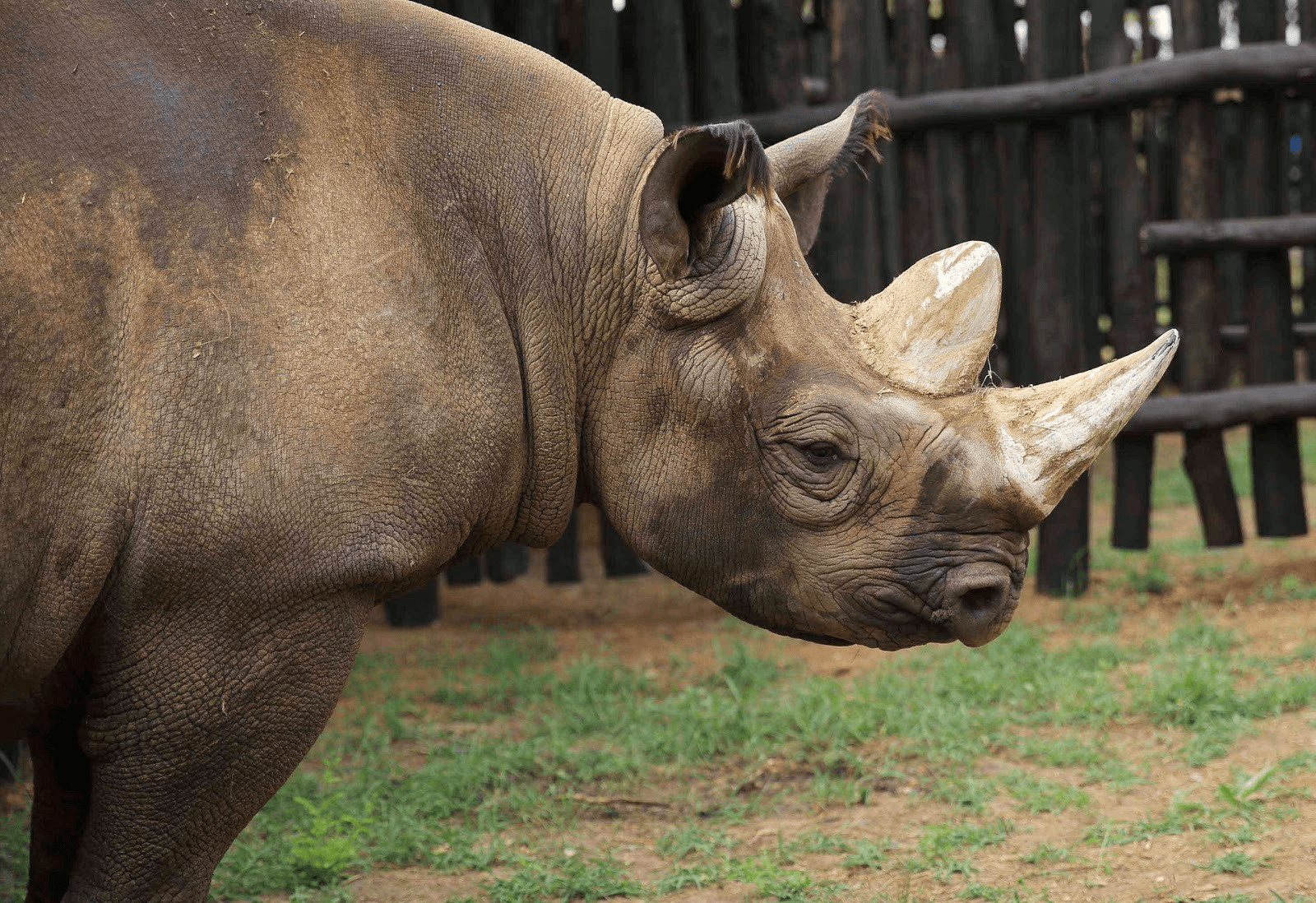

Due to the increasing demand for rhino horns in Asia, South Africa, which is home to the majority of the world’s rhinos, has emerged as a key battleground against poaching. The traditional medical community values these horns for possible medicinal benefits. However, a new approach to addressing this issue has surfaced: putting radioactive material into rhino horns to make them unfit for human consumption.

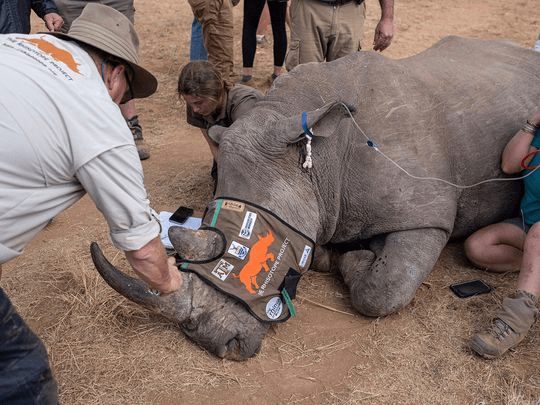

James Larkin, director of the University of the Witwatersrand’s radiation and health physics unit, spearheaded an innovative project. “I put two tiny little radioactive chips in the horn,” Larkin explained to AFP as he administered the radioisotopes to one of the large animals.

This innovative project aims to render rhino horns “essentially poisonous for human consumption,” according to the dean of science at the same university and professor Nithaya Chetty. Notwithstanding the drastic nature of the process, Larkin guaranteed that the rhino’s health and the environment would not be impacted in any anyway by the extremely tiny amount of radioactive particles. While lying on the ground, the tranquillized rhino had no pain.

In February, the environment ministry of South Africa announced that, in spite of massive government efforts to stop the illegal trade, 499 rhinos were killed in 2023—a 11% rise from 2022. This concerning number highlights the critical need for creative solutions, such as the Rhisotope experiment, which includes giving radioactive material to 20 living rhinos. Wearing a green hat and khaki shirt, Larkin expressed his satisfaction, saying that the dose is “strong enough to set off detectors that are installed globally” at international border posts, which were initially designed to prevent nuclear terrorism.

Thanks to handheld radiation detectors, border agents will now be able to recognise illegal rhino horns. Numerous radiation detectors, already present in thousands of ports and airports worldwide, support these efforts.

In black markets, rhino horns are as valuable as cocaine and gold. The orphanage’s founder, Arrie Van Deventer, claims that traditional measures like dehorning and poisoning the horns have not worked to stop poachers. “Maybe this is the thing that will stop poaching,” he said, describing the new method as “the best idea I’ve ever heard.”

As wildebeest, warthogs, and giraffes roamed the conservation area, more than a dozen team members carefully executed the delicate process on another rhino. Larkin drilled a small hole into the horn, inserted the radioisotope, and finished by spraying 11,000 microdots over the horn.

With around 15,000 rhinos living in South Africa, the stakes are high. The project’s final phase involves rigorous aftercare, following “proper scientific protocol and ethical protocol,” said the project’s COO, Jessica Babich.

The team will take follow-up blood samples to ensure the rhinos remain effectively protected.

Larkin emphasized the long-term advantages of this method, pointing out that it would be more affordable than dehorning every 18 months because the radioactive material would remain on the horn for five years. This creative idea has the potential to drastically lower poaching and protect one of the planet’s most iconic species.