Two of the world’s biggest environmental challenges; plastic pollution and rising CO? emissions could be tackled with a single innovation. Chemists at the University of Copenhagen have developed a method to convert discarded PET plastic into a new material that captures carbon dioxide efficiently, transforming waste into a climate solution.

Despite decades of pledges to curb emissions, CO? concentrations in the atmosphere continue to rise. Meanwhile, oceans are choking on plastic, particularly PET — the world’s most common plastic, used in bottles, packaging, and textiles. Once discarded, PET often ends up in landfills or waterways, breaking down into harmful microplastics that contaminate ecosystems.

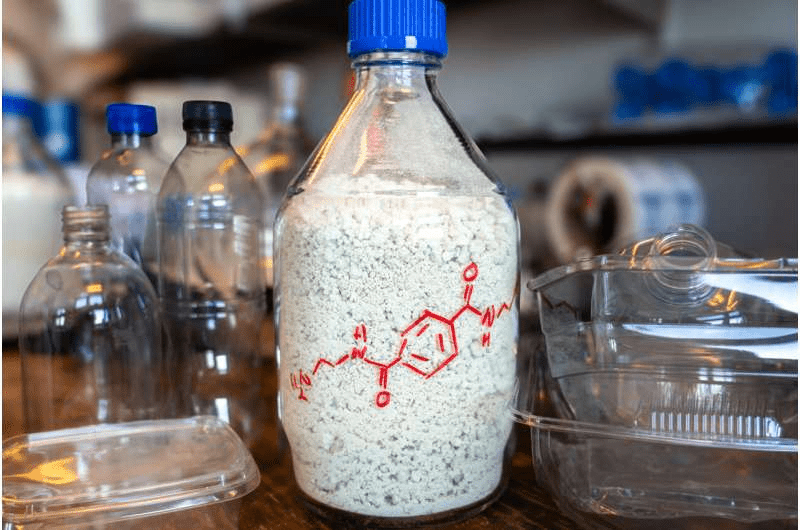

The Copenhagen team has now demonstrated that this trash can be upcycled into a valuable resource. Their process converts PET waste into a new powdered material named BAETA, designed to act as a sorbent for capturing carbon dioxide. BAETA binds CO? with a chemical efficiency that rivals existing capture technologies, while offering unique sustainability advantages.

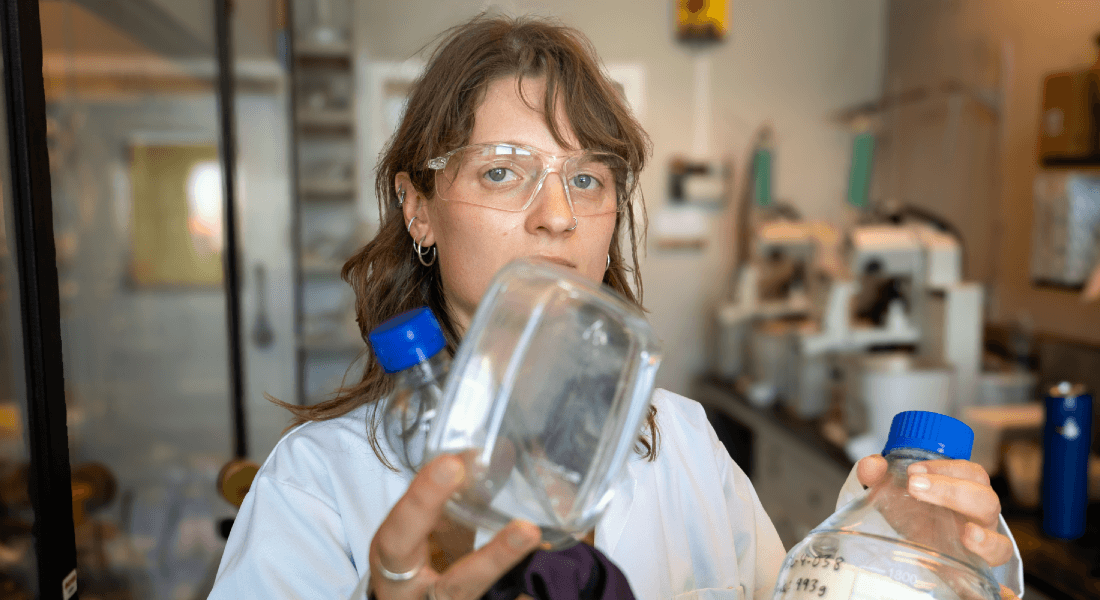

“The beauty of this method is that we solve a problem without creating a new one,” explained Margarita Poderyte, lead author and researcher at the Department of Chemistry. “By turning waste into a raw material that can actively reduce greenhouse gases, we make an environmental issue part of the solution to the climate crisis.”

BAETA is flexible and scalable. The powder can be pelletized and installed in industrial carbon capture systems, where hot exhaust gases from chimneys pass through BAETA filters. Once saturated, the captured CO? can be released with gentle heating, concentrated, and then stored or reused. Unlike some existing technologies, the process operates at ambient temperatures, making it less energy-intensive and easier to scale.

Co-author Jiwoong Lee emphasized the durability of the material. “It works efficiently from normal room temperature up to about 150°C. With that kind of tolerance, it can be used right where the exhausts leave industrial plants. One of the impressive things about this material is that it stays effective for a long time.”

The research team sees BAETA as more than just a lab experiment. Their goal is industrial deployment producing the material in tons and installing it on real-world plants. The main challenge, they argue, is no longer technical but financial: persuading decision-makers and investors to fund scale-up efforts.

The findings of the study were published in Science Advances.