In a fascinating discovery, scientists have successfully revived a worm that had been frozen for a staggering 46,000 years, dating back to a time when woolly mammoths, sabre-toothed tigers, and giant elks roamed the Earth. This remarkable feat sheds light on the incredible resilience of organisms through a state known as cryptobiosis, where life seems suspended between death and existence.

“One can halt life and then start it from the beginning. This a major finding,” he said, adding that other organisms previously revived from this state had survived for decades rather than millennia.

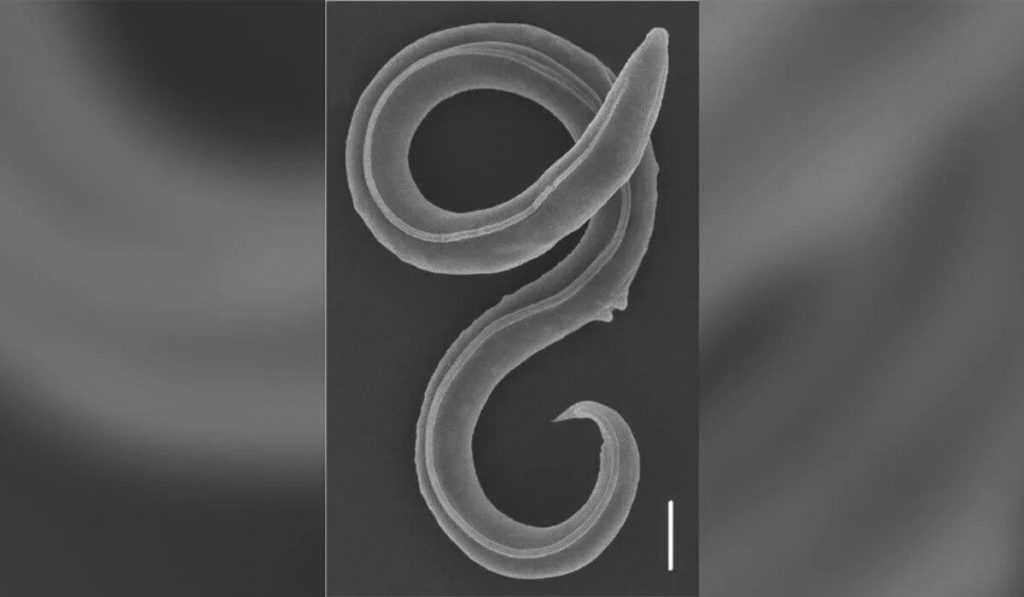

The intriguing discovery took place in the Siberian permafrost, where researchers stumbled upon a previously unknown species of roundworm. These organisms were found to have survived 40 meters (131.2 feet) below the surface in a state of cryptobiosis.

Cryptobiosis allows certain organisms to endure harsh environmental conditions such as complete absence of water or oxygen, extreme temperatures, freezing, and extremely salty conditions. This unique state keeps their metabolic rates at an undetectable level, preserving them in a suspended animation-like state, allowing them to survive for millennia.

The research was conducted by a team of scientists, with Professor Emeritus Teymuras Kurzchalia from the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics in Dresden being one of the key contributors. He explained that the worms remained in a cryptobiotic state, preserving them in a state where they were neither entirely alive nor entirely dead, but somewhere in between.

The revival of the worms was made possible by the diligent work of researchers like Anastasia Shatilovich from the Institute of Physicochemical and Biological Problems in Soil Science in Russia.

She successfully brought two of the worms back to life simply by rehydrating them with water. Around 100 worms were then transported to labs in Germany for further analysis, with Shatilovich taking extra precautions to carry them safely in her pocket.

To determine the age of these ancient worms, scientists employed radiocarbon analysis of the plant material in the sample. The results indicated that the worms had been frozen since a time span between 45,839 and 47,769 years ago. The significance of the find was further enhanced when genetic analysis performed by scientists in Dresden and Cologne revealed that these worms belonged to a previously unidentified species, now named Panagrolaimus kolymaenis.

Remarkably, the researchers found that P. kolymaenis shares certain genetic similarities with C. elegans, another organism often used in scientific studies. They possess a “molecular toolkit,” including the production of a sugar called trehalose, which plays a crucial role in their ability to withstand cryptobiosis.

This sugar acts as a protective agent, enabling the worms to endure freezing and dehydration, further demonstrating their extraordinary survival capabilities.

“To see that the same biochemical pathway is used in a species which is 200, 300 million years away, that’s really striking,” said Philipp Schiffer, research group leader of the Institute of Zoology at the University of Cologne and one of the scientists involved in the study. “It means that some processes in evolution are deeply conserved.”

Studying these ancient worms not only allows scientists to gain a deeper understanding of the past but also unlocks valuable insights that can be applied in various scientific disciplines. By unraveling the mechanisms of cryptobiosis and the secrets of these resilient organisms, researchers hope to develop new technologies and techniques to preserve biological materials and even explore the possibilities of space travel and colonization.

“By looking at and analyzing these animals, we can maybe inform conservation biology, or maybe even develop efforts to protect other species, or at least learn what to do to protect them in these extreme conditions that we have now,” he told CNN.