Earth is not a static world. Over immense stretches of time, continents drift, collide, and fuse, repeatedly transforming the planet’s geography. These slow geological cycles have shaped oceans, climates, and mass extinctions long before humans appeared. According to new research, one such transformation still lies far ahead, yet its consequences are stark enough to raise unsettling questions about humanity’s long-term survival.

A recent peer-reviewed study published in Nature Geoscience models the distant future of Earth roughly 250 million years from now. Using advanced climate simulations, tectonic projections, and atmospheric models, scientists explored what happens when today’s continents merge into a single supercontinent known as Pangea Ultima. Their conclusion is sobering. The planet that emerges would be radically different from the one humans evolved to inhabit.

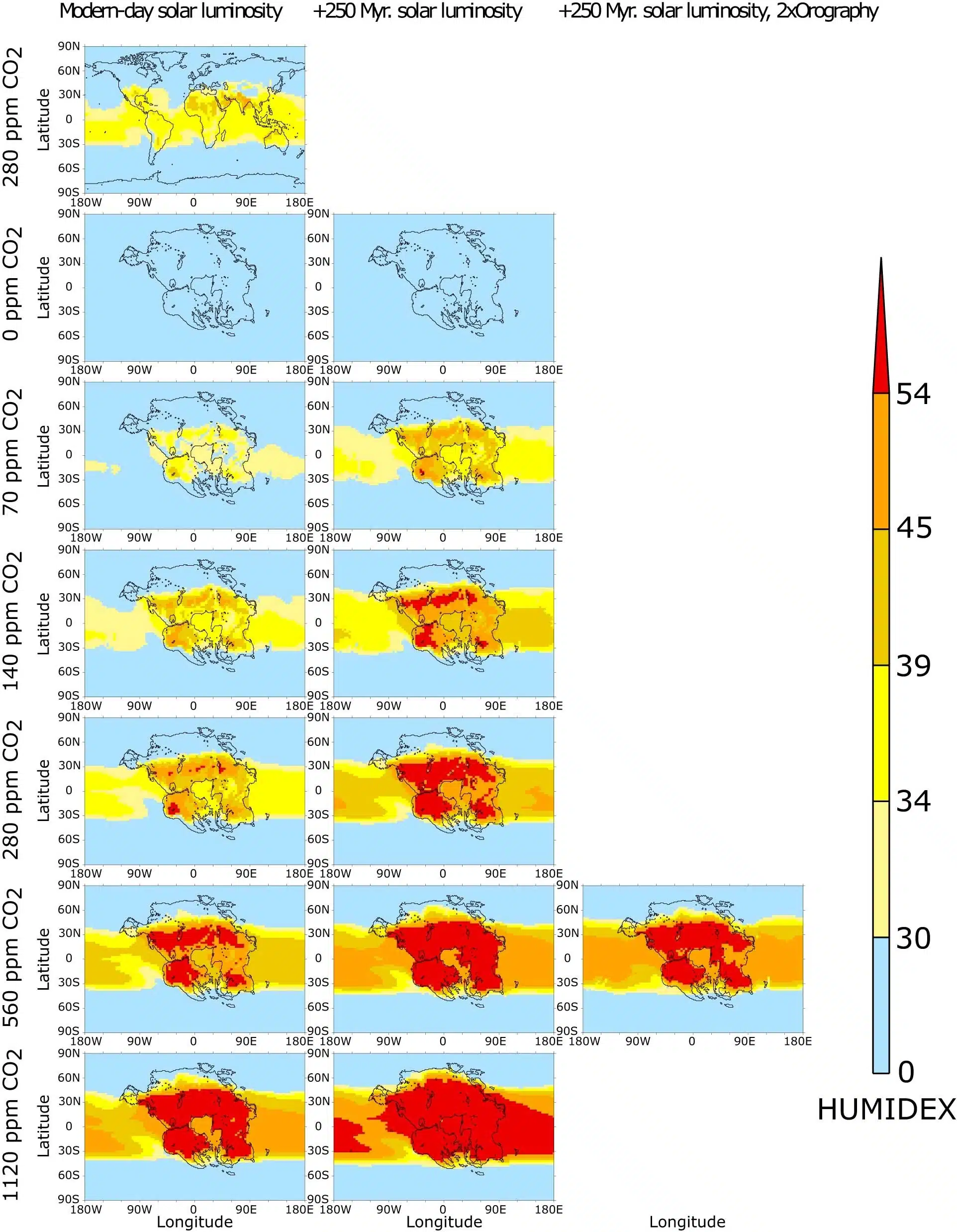

Warmest month HUMIDEX for each experiment at present day (column 1), +2.5% present day solar luminosity (column 2) and +2.5% present day solar luminosity with a doubling of the topography (column 3) at 0?pm, 70?pm, 140?pm, 560?pm and 1120 ppm CO2. Credit: Nature Geoscience

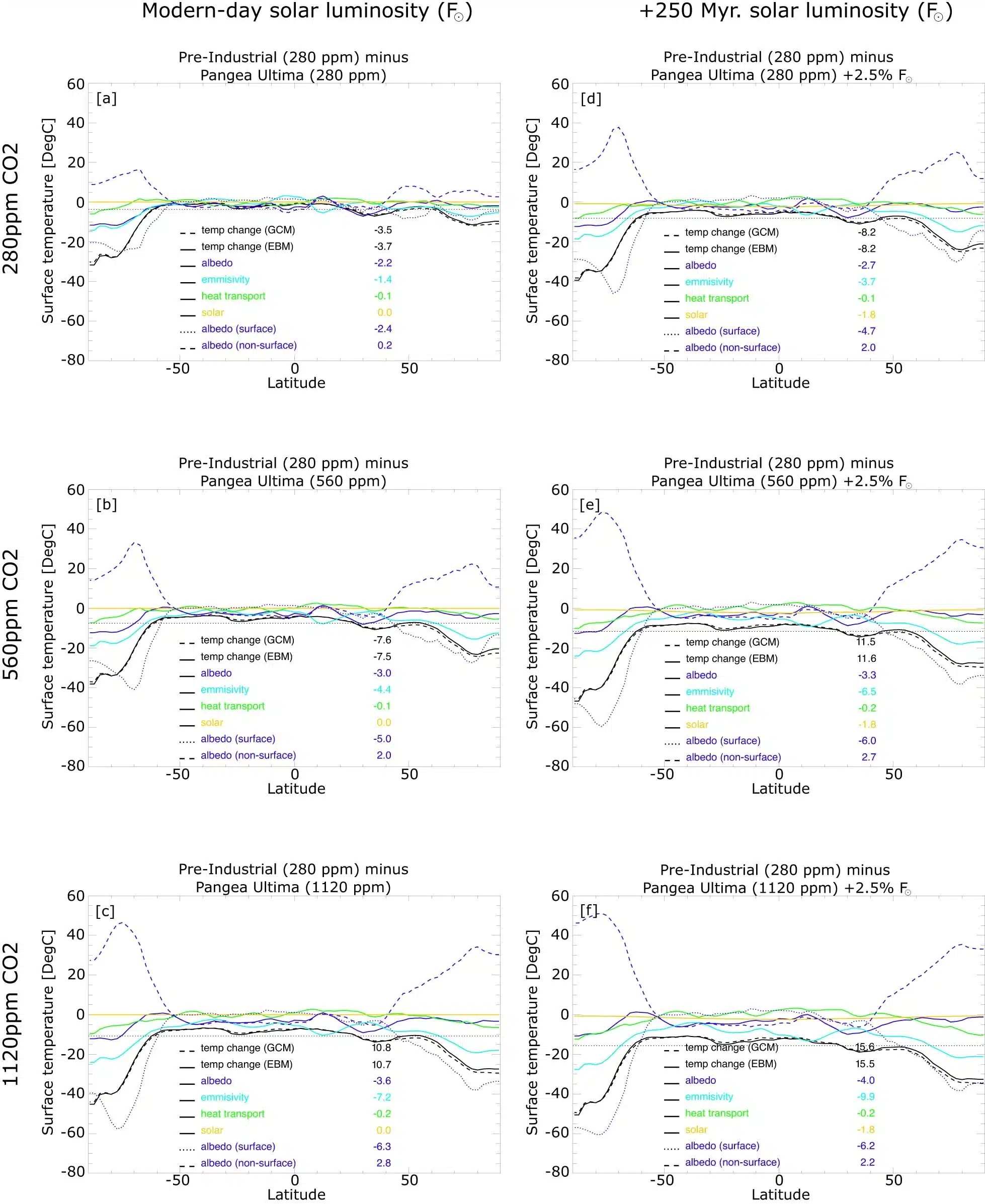

When continents concentrate into one vast landmass, Earth loses much of the ocean surface that currently helps regulate temperature. In the models, Pangea Ultima forms largely near the equator, where solar energy is strongest. At the same time, the Sun itself is expected to shine slightly brighter in hundreds of millions of years, adding another layer of warming. Together, these factors drive global land temperatures dramatically higher.

The simulations show average land temperatures rising by up to 30 degrees Celsius compared to pre-industrial conditions. Many regions would experience prolonged heat well beyond the tolerance of mammals. Researchers focused on heat stress indicators such as wet-bulb temperature, a measure combining heat and humidity. Once wet-bulb temperatures exceed 35 degrees Celsius, the human body can no longer cool itself effectively, even with unlimited water.

Energy balance model analysis for each experiment relative to the 280 ppm Pangea Ultima experiment. Credit: Nature Geoscience

Under moderate carbon dioxide levels, only about 16 percent of the future supercontinent remains within survivable limits for mammals. At higher CO? concentrations, that habitable area shrinks to just 8 percent. The rest of the land becomes a mix of extreme heat, humidity, and aridity. Vast deserts dominate the interior, while food and fresh water become increasingly scarce.

Carbon dioxide plays a critical role in this scenario. As continents collide, volcanic activity intensifies, releasing large amounts of CO? into the atmosphere. At the same time, natural carbon removal processes slow down because dry landscapes limit chemical weathering. The result is a persistent greenhouse climate that lasts millions of years.

The study draws parallels to past mass extinctions, particularly the end-Permian event, when rapid warming wiped out most life on Earth. While this future outcome is unimaginably distant, the research underscores a fundamental truth. Planetary habitability is fragile. Even without human influence, Earth’s own internal rhythms may one day make it unrecognizable and, eventually, uninhabitable for complex life.