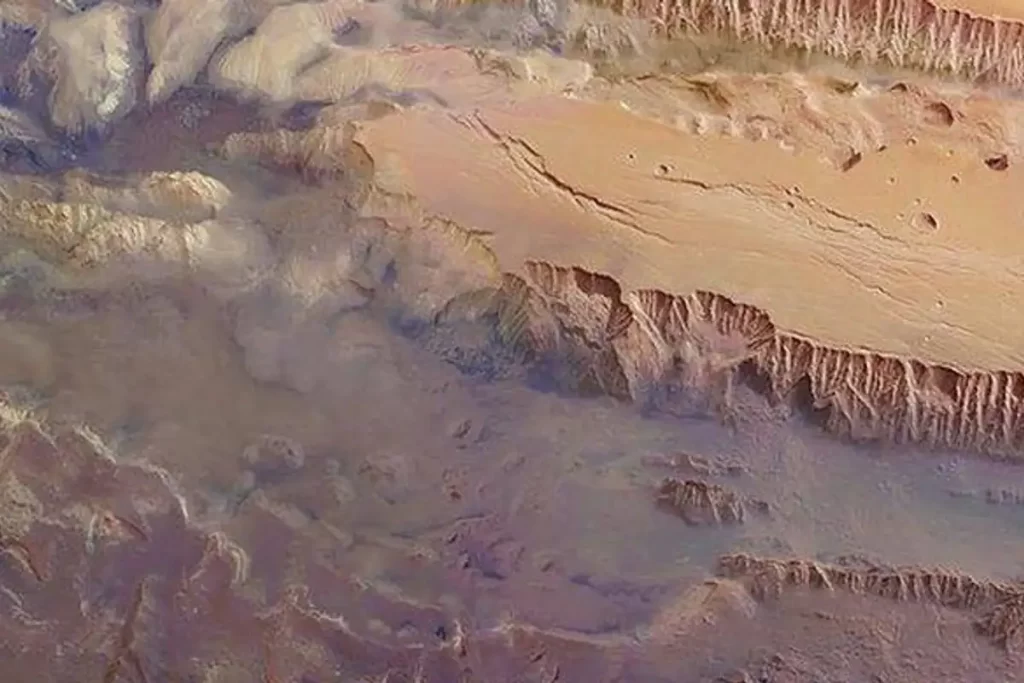

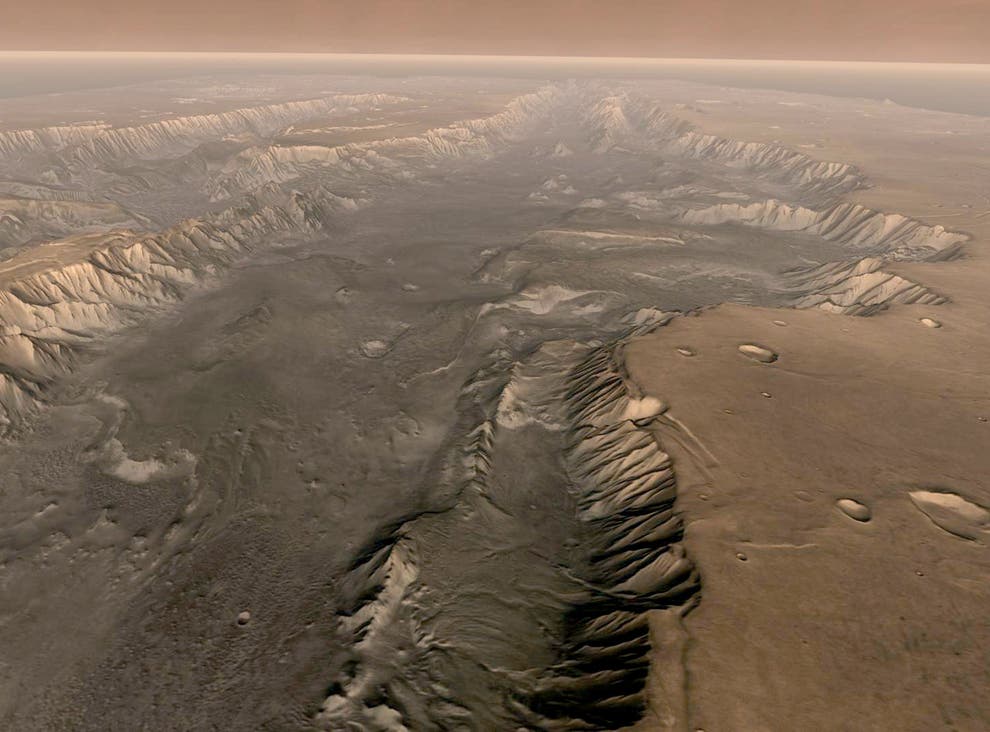

The European Space Agency’s ExoMars satellite discovered evidence of a massive water deposit beneath the Valles Marineris Martian canyon system, one of the greatest canyons in the Solar System—about ten times as long as the Grand Canyon in Arizona.

Scientists examined data from the Trace Gas Orbiter’s (TGO) Fine-Resolution Epithermal Neutron Detector (Frend) instrument, which monitors hydrogen in the uppermost meter of Mars’ soil—a gauge of water content. The study, published in the journal Icarus, discovered an area in the canyon roughly the size of the Netherlands that had an exceptionally significant amount of hydrogen.

“Assuming the hydrogen we see is bound into water molecules, as much as 40 percent of the near-surface material in this region appears to be water,” study lead author Igor Mitrofanov of the Russian Academy of Sciences in Moscow said.

“With TGO, we can look down to one meter below this dusty layer and see what’s really going on below Mars’ surface—and, crucially, locate water-rich ‘oases’ that couldn’t be detected with previous instruments,” Dr. Mitrofanov added.

While previous research has discovered clues of underground water in the Red Planet’s mid-latitudes and pools of liquid water beneath the Martian south pole, these potential deposits are a few kilometers below ground and less accessible to future exploration than those found near the surface.

In this region of Mars, the study has discovered indications of a “large, not-too-deep, easily exploitable reservoir of water.” The scientists believe that a central area of Valles Marineris could be flooded with water, similar to sites like Siberia, where water ice persists under dry soil due to continual low temperatures.

The researchers looked at data from the Frend instrument, which used neutron detection to map the hydrogen composition of Mars’ soil, from May 2018 to February 2021.

“Neutrons are produced when highly energetic particles known as ‘galactic cosmic rays’ strike Mars; drier soils emit more neutrons than wetter ones, and so we can deduce how much water is in a soil by looking at the neutrons it emits,” study co-author Alexey Malakhov from the Russian Academy of Sciences explained.

“Frend’s unique observing technique brings far higher spatial resolution than previous measurements of this type, enabling us to now see water features that weren’t spotted before,” Dr. Malakhov added.

The researchers assume that the observed water deposits are either ice or water chemically bonded with other minerals in the soil. However, they claim that the minerals found in this region of Mars typically contain only a tiny proportion of water—”much less than is evidenced by these new observations,” according to earlier studies.

“Overall, we think this water more likely exists in the form of ice,” Dr. Malakhov said.

However, according to scientists, more research into this section of the canyon is needed to clarify what type of water these deposits contain.

While the temperature and pressure conditions near the equator lead water ice to evaporate, researchers claim a perfect combination of temperature, pressure, and hydration must exist to prevent water loss from the region.

They believe Valles Marineris possesses a unique, as-yet-unknown combination of variables that aids in the preservation of the water. Alternatively, the researchers hypothesize that the water is supplied via an unknown process.