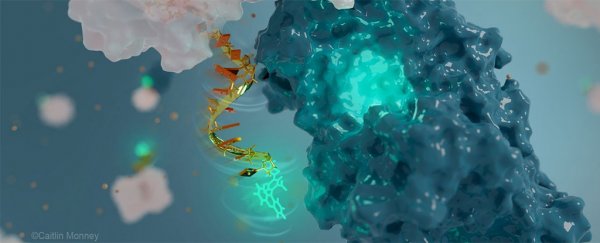

Scientists have built the tiniest antenna ever made and it is only five nanometers long. It is important to notice that this isn’t made to transmit radio waves but to glean the secrets of ever-changing proteins.

The nanoantenna is made from DNA. It’s fluorescent, which means it uses light signals to record and report information. These light signals can be used to study the movement and change of proteins in real-time.

It is innovative how its receiver part of it is also used to sense the molecular surface of the protein it’s studying. That results in a distinct signal when the protein is fulfilling its biological function.

“Like a two-way radio that can both receive and transmit radio waves, the fluorescent nanoantenna receives light in one color, or wavelength, and depending on the protein movement it senses, then transmits light back in another color, which we can detect,” says chemist Alexis Vallée-Bélisle, from the Université de Montréal (UdeM) in Canada.

The main job of the antenna is to measure the structural changes in proteins with time. However, proteins are constantly changing.

“Experimental study of protein transient states remains a major challenge because high-structural-resolution techniques, including nuclear magnetic resonance and X-ray crystallography, often cannot be directly applied to study short-lived protein states,” the team explains in their paper.

The latest DNA synthesizing technology – some 40 years in development – can produce bespoke nanostructures of different lengths and flexibilities, optimized to fulfill their required functions.

This super-small DNA can capture very short-lived protein states. This means that there are several potential applications for this in both biochemistry and nanotechnology.

“For example, we were able to detect, in real-time and for the first time, the function of the enzyme alkaline phosphatase with a variety of biological molecules and drugs,” says chemist Scott Harroun, from UdeM. “This enzyme has been implicated in many diseases, including various cancers and intestinal inflammation.”

While exploring “the universality” of their design, the team successfully tested their antenna with three different model proteins – streptavidin, alkaline phosphatase, and Protein G.

“Nanoantennas can be used to monitor distinct biomolecular mechanisms in real-time, including small and large conformational changes – in principle, any event that can affect the dye’s fluorescence emission,” the team writes in their paper.

The researchers are now looking to create a commercial startup so that the nanoantenna technology can be used widely.

“Perhaps what we are most excited by is the realization that many labs around the world, equipped with a conventional spectrofluorometer, could readily employ these nanoantennas to study their favorite protein, such as to identify new drugs or to develop new nanotechnologies,” says Vallée-Bélisle.

The research has been published in Nature Methods.