This new research is challenging long-held beliefs about life and death.

A group of Yale University researchers recently employed a new technology to regenerate cells in various organs of recently deceased pigs, restoring the animals’ cells to function. The recent findings pose deep ethical considerations about how medicine defines death while also hinting at new possibilities for gathering human organs for transplant.

The research is still in its early experimental stages and will be many years before it can be used in humans. However, it may eventually assist in prolonging the lives of people whose hearts have stopped beating. The technology also has the potential to significantly alter how organs are gathered for transplant and enhance their availability.

“The demise of cells can be halted,” Dr. Nenad Sestan, a professor of neuroscience at the Yale School of Medicine and an author of the new research, said during a news conference.

“We restored some functions of cells across multiple organs that should have been dead.”

The scientists made this vital progress by building pumps, sensors, and tubing systems connecting to pig arteries. Then they created a recipe containing 13 medical medications blended with blood and injected into the animal’s circulatory systems. The study builds on prior work at Yale that showed that specific brain cell damage might be restored if the blood supply was shut off.

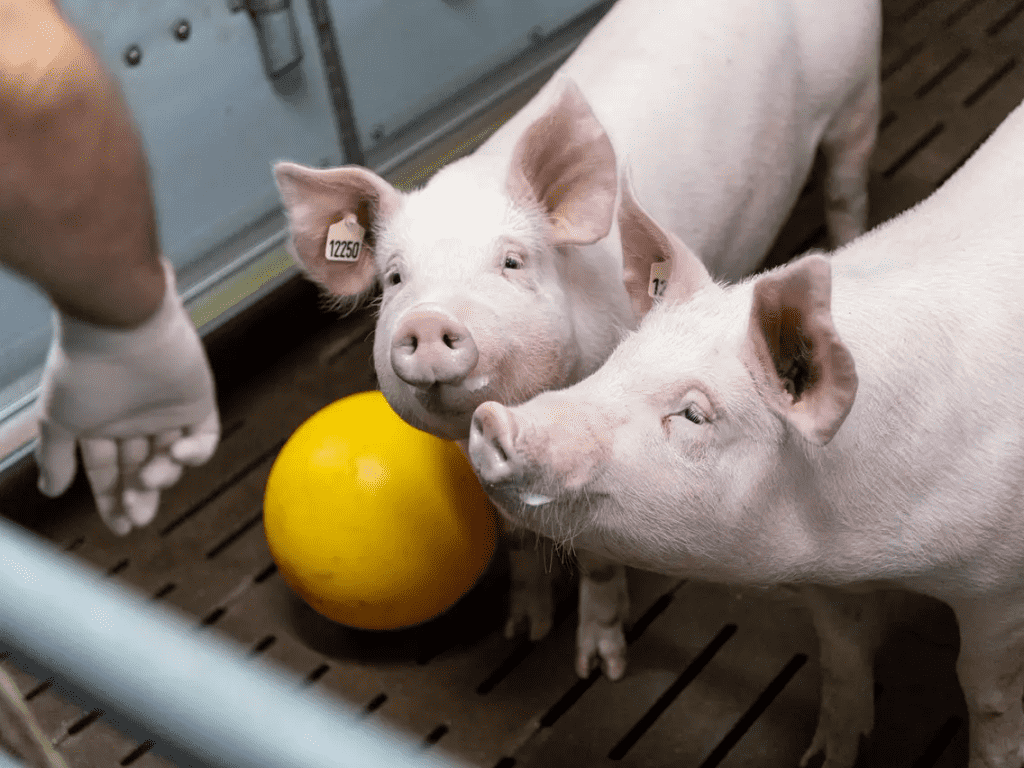

The researchers gave anesthetized pigs heart attacks to see how well the new device, called OrganEx, functions. Then, after the pigs had been rendered unconscious for an hour, the researchers utilized brain inhibitors to prevent the animals from regaining awareness during the following experiments.

The researchers then started utilizing the OrganEx system. First, they compared its performance to that of ECMO, a modern method of life support in which a machine pumps blood throughout the body while oxygenating it.

OrganEx boosted circulation and stimulated cell healing. For example, the researchers observed cardiac cells contracting and electrical activity returning. According to the study, other organs, including the kidneys, also improved.

The researchers were taken aback by the pigs treated with OrganEx. During the experiment, the dead pigs’ heads and necks moved independently. The animals, however, remained heavily sedated.

“We can say that animals were not conscious during these moments, and we don’t have enough information to speculate why they moved,” Sestan said.

The OrganEx study is a single trial in a laboratory setting in which researchers had complete control over the pigs’ death and treatment. But, still, even the preliminary findings still suggest possibilities that would have appeared in science fiction just a few years ago.

The Yale researchers do not anticipate using OrganEx for medical treatment any time soon. However, the report claims that even though they have applied for a patent for the new technology, they are making the system’s protocols and procedures publicly available for nonprofit or academic use.

“Before you hook this up to a person to try to undo whole body ischemic damage in a human being, you’d need to do a lot more work. Not that it couldn’t be done, but that’s going to be a long ways away,” said Stephen Latham, director of the Yale Interdisciplinary Center for Bioethics.

“There’s a great deal more experimentation that would be required.”

However, the potential for new technology poses serious medical ethics issues – and gives unresolved issues a new spin. For example, using technologies like ECMO to preserve organs in people declared legally dead based on cardiorespiratory criteria has been a topic of ethical discussion.

It’s also possible that OrganEx will change the guidelines for when medical professionals can ethically allow a patient to pass away and then save their organs for donation.

The study is published in the journal Nature.