In a bold step toward self-sustaining artificial life, scientists at Columbia University have unveiled a class of robots capable of physically merging, adapting, and evolving together effectively “cannibalizing” each other to become more efficient and capable.

The innovation centers around a deceptively simple module called the Truss Link, a rod-shaped unit with the ability to expand, contract, crawl, and magnetically link with others of its kind. On its own, a Truss Link looks modest. But connect a few, and they begin to show signs of rudimentary cooperative intelligence, transforming themselves in shape, motion, and function.

According to Wyder, who works at Columbia Engineering and the University of Washington, “True autonomy means robots must not only think for themselves but also physically sustain themselves.” In other words, these machines aren’t just meant to think they’re meant to grow, repair, and evolve, like early biological organisms.

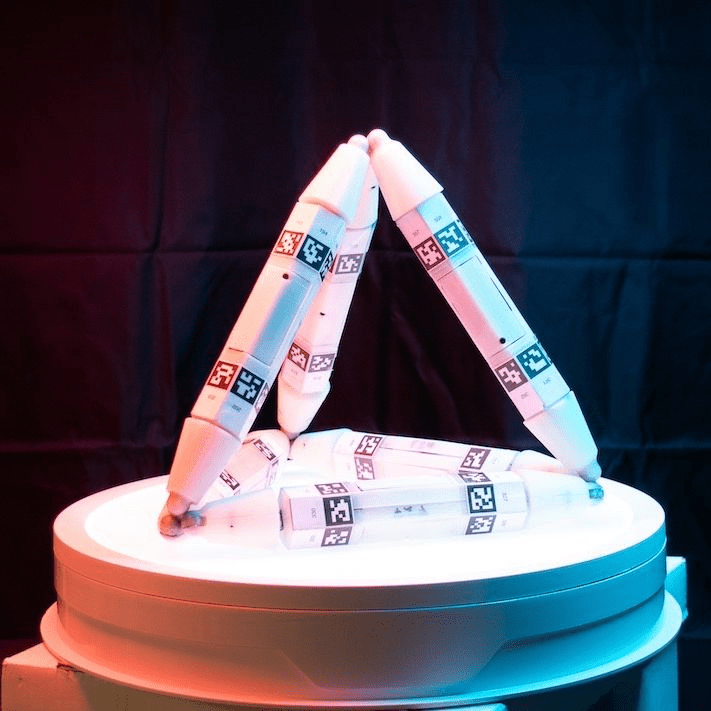

The study, published in Science, includes a series of fascinating experiments in which the Truss Links actively seek out and fuse with each other. In one sequence, six disconnected units crawl together under remote control and assemble into a larger robot with a triangular shape and an extra “tail.” This hybrid structure then navigates its environment, even throwing itself off a ledge before reconfiguring into a stable 3D tetrahedron. Once in that form, it adds another module as a “walking stick,” allowing it to climb an incline 66% faster than before.

The researchers refer to this capability as “robot metabolism,” a mechanical counterpart to how biological entities absorb nutrients or each other to grow and survive. In one particularly telling demonstration, a robot discards a low-battery module and replaces it with a new one, an act of self-preservation that mimics natural metabolic exchange. In another, a robot extends a part of itself to hoist another robot upward so it can complete its own transformation. These bots aren’t just adapting they’re helping one another evolve.

Wyder likens his modular robots to amino acids the building blocks of life noting that with just 20 standard amino acids, nature has created an infinite variety of proteins. “In robotics, we’ve been just replicating the results of biological evolution,” Wyder told Ars Technica. “I say we need to replicate its methods.”

Of course, these robots aren’t fully autonomous yet. For now, they still require human teleoperation, and their ability to spontaneously form complex shapes like tetrahedrons remains mostly theoretical. In computer simulations, researchers found the bots could create most shapes on their own with random motor movements within 2,000 attempts, though the tetrahedron proved elusive due to its complexity. Still, the team insists that with enough iterations, it’s only a matter of time before the bots could evolve these shapes independently.

What’s next? Wyder says the plan is to develop more module types essentially, to expand the robot’s amino acid library. “Life uses around 20 different amino acids to work, so we’re currently focusing on integrating additional modules with various sensors,” he said.