Imagine a robot that not only recognizes objects but actually feels them, registering the heat of a stove, the pressure of a handshake, or even the pain of a cut. That once-fantastical vision is now closer to reality, thanks to a groundbreaking new type of electronic “skin” developed by scientists.

The futuristic skin is crafted from a stretchy, gelatin-based hydrogel infused with electrical conductivity. What sets it apart isn’t just its flexibility, but its integration of multi-modal sensors, a single sensor type capable of recognizing various physical cues like pressure, heat, and even damage.

This approach breaks from tradition. Historically, robotic skins relied on an assortment of sensors for each type of stimulus: one for pressure, another for temperature, and so on. But this setup often led to cross-signal interference and required fragile, silicone-based materials prone to damage. The new hydrogel design not only avoids these pitfalls but also offers durability, simplicity, and cost-effectiveness.

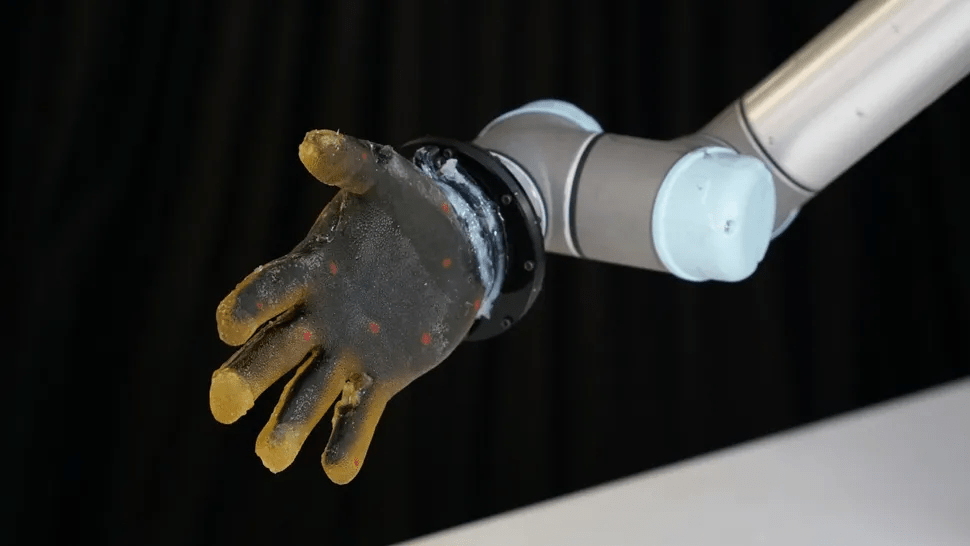

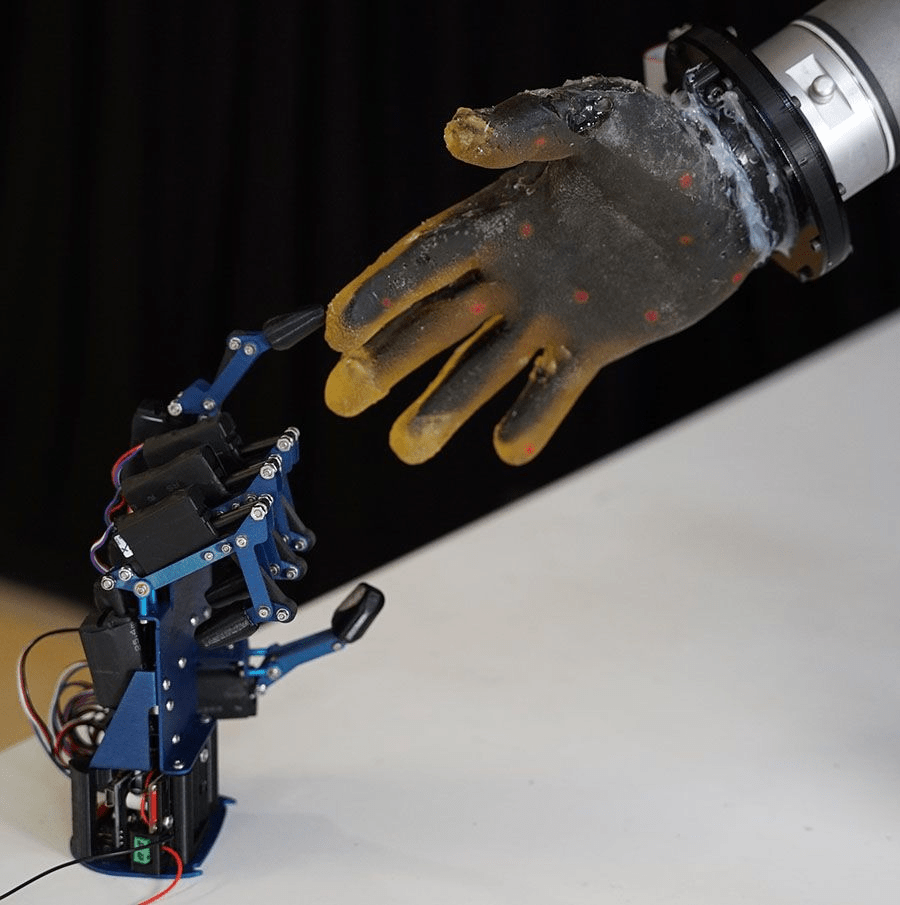

To test their invention, researchers molded the hydrogel into the shape of a human hand and embedded it with various electrode configurations. The hand underwent a series of physical assaults: it was blasted with a heat gun, poked by fingers and robotic arms, and even sliced open with a scalpel. Brutal as it may sound, the goal was to simulate real-world interactions and evaluate the skin’s responsiveness.

The results were striking. The artificial hand gathered more than 1.7 million data points from over 860,000 conductive pathways, offering a dense stream of sensory information. This massive dataset was used to train a machine learning model capable of interpreting and distinguishing between different types of touch.

“We’re not quite at the level where the robotic skin is as good as human skin,” admitted Thomas George Thuruthel, study co-author and robotics lecturer at University College London. “But we think it’s better than anything else out there at the moment.”

While the primary focus is on humanoid robots and prosthetic limbs, the potential applications extend much further. Automotive manufacturers could use the skin in safety systems, and disaster relief operations might benefit from robots that can feel their way through hazardous environments. With its resilience and ease of production, this new material could become a foundational element in next-generation machines that interact with the world in profoundly human ways.

The work also marks a pivotal moment in the ongoing race to close the gap between artificial and biological touch. “Our method is flexible and easier to build than traditional sensors,” Thuruthel noted, “and we’re able to calibrate it using human touch for a range of tasks.”