Imagine an engine so tiny it’s smaller than a human cell yet hot enough to outshine the Sun. Scientists from King’s College London (KCL) and their collaborators have created just that: the world’s smallest engine, powered by a single microscopic particle levitating in a vacuum. This minuscule marvel was heated to a staggering 10 million degrees Celsius (about 18 million °F), making it millions of degrees hotter than the Sun’s surface and three times hotter than its corona, according to ZME Science.

But while the extreme temperature grabs headlines, the real fascination lies deeper in how this engine challenges our very understanding of the laws of physics.

At its core, an engine converts energy into motion. In classical physics, that’s a straightforward process governed by thermodynamics. Yet, when scientists shrink the machinery down to the scale of atoms and particles, the rules start to bend.

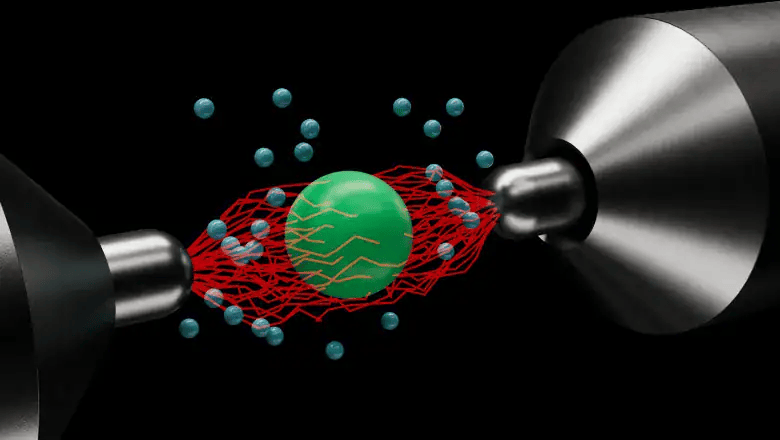

To build this microscopic engine, researchers used a quadrupole ion trap (Paul Trap), a device that suspends a charged microparticle in a near-perfect vacuum using oscillating electric fields. By bombarding this particle with random, “noisy” voltages, they made it jiggle violently, producing heat through motion.

But unlike a traditional engine, this one behaves unpredictably. Sometimes, instead of heating up when exposed to energy, the particle cooled down, a bizarre violation of what thermodynamics would normally allow. This randomness, known as stochastic behavior, defines a growing field called stochastic thermodynamics, where the familiar laws of physics only hold on average, not in every individual event.

As Molly Message, the study’s lead author and a PhD student at King’s College London, explains: “Engines and the types of energy transfer that occur within them are a microcosm of the wider universe. Studying the steam engine brought about the field of thermodynamics, which in turn revealed some of the fundamental laws of physics. The continued study of engines into new regimes offers the potential to expand our understanding of the universe and the processes that drive its development.”

She adds, “By getting to grips with thermodynamics at this unintuitive level, we can design better engines in the future and experiments which challenge our understanding of nature.”

It may sound like abstract physics, but this tiny engine has profound implications for biology. At the microscopic level, life itself operates like a collection of stochastic engines proteins, enzymes, and molecular machines all function amid random thermal noise.

The researchers realized that their setup could act as an “analogue computer” to model how proteins fold, one of the most challenging mysteries in biology.

Proteins, made of long chains of amino acids, must fold into precise 3D structures to perform their functions. When they misfold, they can trigger diseases such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, or cystic fibrosis. AI tools like Google DeepMind’s AlphaFold, which won a Nobel Prize in Chemistry, can predict the final shape of proteins but not the complex journey from chain to folded form.

Here, the KCL particle engine steps in. By tuning electrical fields and introducing controlled noise, the team can simulate the chaotic environment inside a living cell, offering a physical analogue of protein folding in real time.

As the researchers describe it: “The advantage of our method over conventional digital models like AlphaFold is ease. Proteins fold over milliseconds, but the atoms which make them move over nanoseconds. These divergent timescales make it very difficult for a computer to model them. By just observing how the microparticle moves and working out a series of equations based on that, we avoid this problem entirely.”

This research was published in Physical Review Letters.