On Tuesday, nuclear scientists announced that they had generated 1.3 megajoules (MJ) of energy for the first time with lab-based fusion reactions using lasers the size of three football fields, potentially cementing the ground for a new clean energy source and a better technique to assess our increasing proximity to “greater than unity” levels of energy generation.

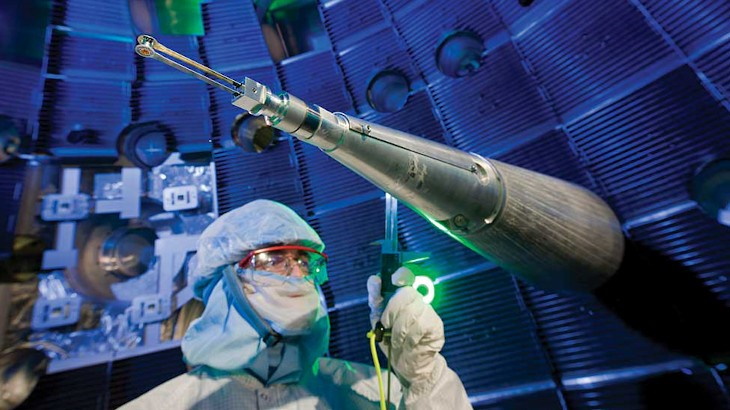

On 8th Aug, the experiment took place at the National Ignition Facility at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) (NIF). Experts centered a massive array of nearly 200 laser beams on a tiny spot to create a mega blast of energy—eight times more than they had previously done. Although the energy only lasted 100 trillionths of a second, it moved scientists closer to fusion ignition, the point at which they produce more energy than they consume.

“This result is a historic advance for inertial confinement fusion research,” said Kim Budil, the director of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, which operates the National Ignition Facility in California, where the experiment took place this month.

The NIF generates temperatures up to 180 million degrees Fahrenheit and pressures with more than 100 billion Earth atmospheres. Such extremely hot conditions cause hydrogen atoms to fuse, generating massive amounts of energy in a reaction known as thermonuclear fusion.

However, generating such massive power yields has forever stayed the desired goal for inertial confinement fusion research. The recent lab results show that the fusion ignition benchmark has been successfully achieved.

Some scientists consider nuclear fusion to be the potential energy of the future, mainly because it produces little waste and no greenhouse gases. It differs from fission, a technique currently used in nuclear power plants, where the bonds of heavy atomic nuclei are broken to release energy. In the fusion process, two light atomic nuclei are “married” to create a heavy one. This indicates that fusion will continue to work until it can generate more power than can be poured into a machine. The recent experiment yielded a fusion yield of roughly two-thirds of the input laser energy, bringing the fusion yield closer to the “greater than unity” limit.

“The NIF teams have done an extraordinary job,” said Professor Steven Rose, co-director of the center for research in this field at Imperial College London.

“This is the most significant advance in inertial fusion since its beginning in 1972.”

But, as Jeremy Chittenden, co-director of the same London center, cautioned that making this a usable energy source will be difficult.

“Turning this concept into a renewable source of electrical power will probably be a long process and will involve overcoming significant technical challenges,” he said.

Though our planet may benefit from a fully clean and powerful energy source to better our current living conditions, there are some caveats. Aside from technical difficulties, there may be some bureaucratic constraints as well. Furthermore, governments’/companies’ incentives to keep resources scarce could significantly halt the use of fusion power. Let us see if the future of energy benefits everyone or not.