How have Rome’s ancient aqueducts and architectural wonders, such as the Pantheon, with the world’s biggest unreinforced concrete dome, withstood the test of time? Structures built by the ancient Romans are still standing strong after 2,000 years. while skyscrapers and other modern structures are projected to last only 50 to 100 years. After this time, they are no longer safe to use and are typically dismantled by authorities.

Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and other universities believe they have solved the mystery of the 2,000-year-old structures’ durability: self-healing concrete. The key element in the ancient Roman concrete was ignored in prior studies, according to the researchers, whose findings were published in the newest issue of the journal Science Advances.

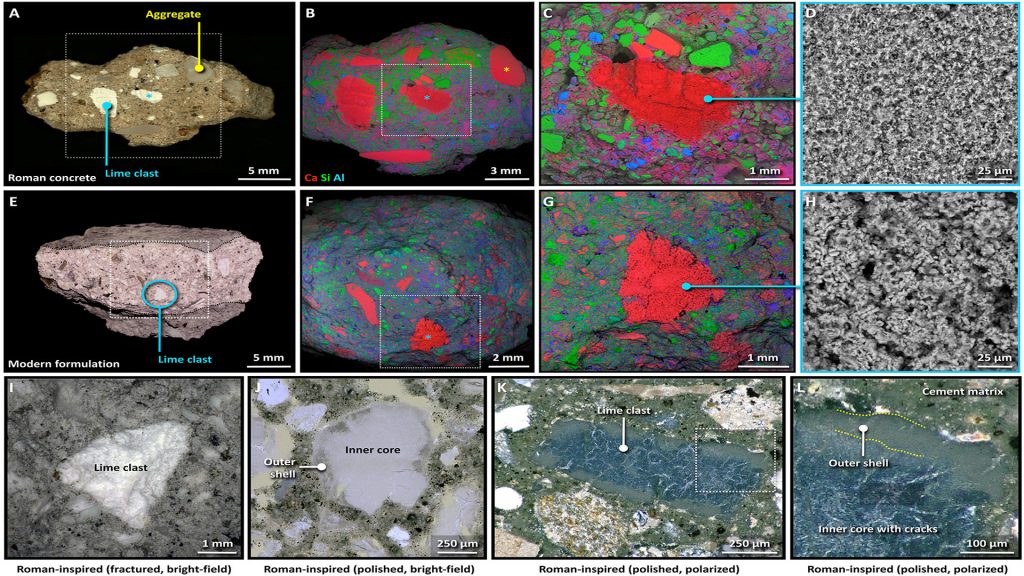

The usage of volcanic ash from Pozzuoli on the Bay of Naples, which was exported around the Roman empire for construction, has been attributed to the durability of the Roman concrete. However, the researchers concentrated on another component of the old concrete mix: microscopic white fragments known as “lime clasts.”

“Ever since I first began working with ancient Roman concrete, I’ve always been fascinated by these features,” said MIT professor of civil and environmental engineering Admir Masic, an author of the study. “These are not found in modern concrete formulations, so why are they present in these ancient materials?” The researchers said the lime clasts had been thought to be the result of “sloppy mixing practices” or poor-quality raw materials. But they are in fact what gives the ancient concrete a “previously unrecognized self-healing capability.”

The researchers studied 2,000-year-old Roman concrete samples from the masonry mortar of a city wall in Privernum, Italy, for the study. They discovered that the “super-durable character” of the concrete was due to a procedure known as “hot mixing,” in which the Romans blended quicklime with water and volcanic ash at high temperatures.

“The benefits of hot mixing are twofold: first, when the overall concrete is heated to high temperatures, it allows chemistries that are not possible if you only use slaked lime, producing high-temperature-associated compounds that would not otherwise form.” “Second, this increased temperature significantly reduces curing and setting times since all the reactions are accelerated, allowing for much faster construction,” said Professor Masic. The study was published in the journal Science Advances.