A decades-old quantum puzzle may finally have an experimental stand-in thanks to superfluid helium. By replacing the impossible conditions required by Schwinger’s famous theory with a thin film of frictionless liquid helium, physicists at the University of British Columbia (UBC) have proposed a way to watch vortex pairs spontaneously emerge.

In 1951, Nobel-winning physicist Julian Schwinger suggested that a strong, uniform electric field could pull matter from nothing, conjuring electron-positron pairs out of the vacuum via quantum tunneling. The idea known as the Schwinger effect has fascinated scientists for generations. But there is a catch: the required electric fields are unimaginably powerful, far beyond what current experiments could ever achieve. For that reason, the effect has remained entirely theoretical.

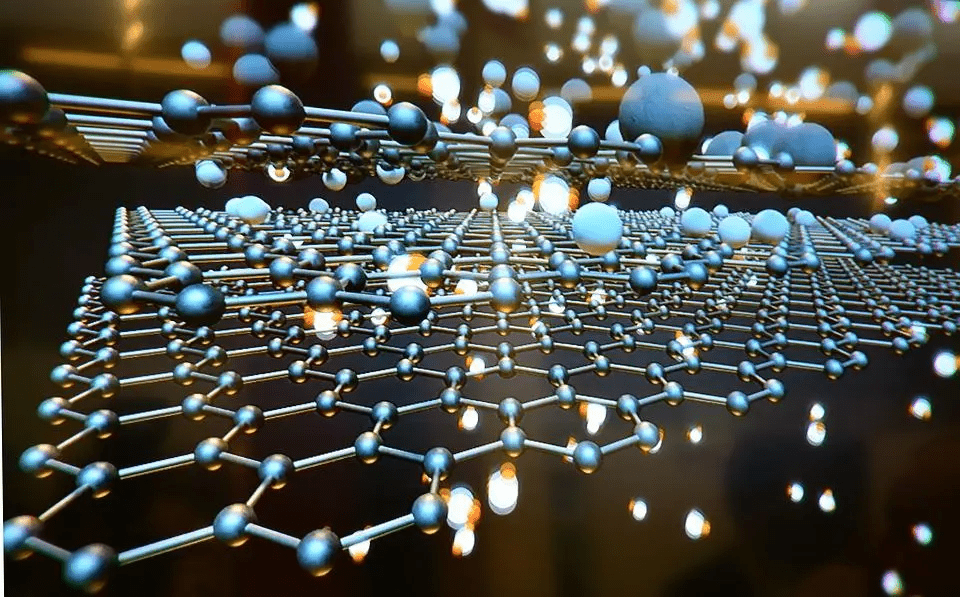

Now, UBC physicist Philip Stamp and colleague Michael Desrochers have outlined an ingenious analog. Instead of an empty vacuum blasted with electric fields, they envision a wafer-thin film of superfluid helium-4. At just a few atomic layers thick, helium-4 can be cooled to a state where it flows without friction—effectively creating a kind of “vacuum” of its own.

“Superfluid Helium-4 is a wonder,” Stamp explained. “At a few atomic layers thick it can be cooled very easily to a temperature where it’s basically in a frictionless vacuum state. When we make that frictionless vacuum flow, instead of electron-positron pairs appearing, vortex/anti-vortex pairs will appear spontaneously, spinning in opposite directions to one another.”

The researchers describe how this system could serve as a test bed for processes that usually belong to the realm of cosmology and particle physics. “We believe the Helium-4 film provides a nice analog to several cosmic phenomena,” Stamp said. “The vacuum in deep space, quantum black holes, even the very beginning of the Universe itself. And these are phenomena we can’t ever approach in any direct experimental way.”

But while the parallels are intriguing, Stamp is quick to stress that the helium system is valuable in its own right. Beyond its role as an analog, the superfluid model challenges old assumptions about vortex behavior. Previous work treated vortex mass as a fixed quantity. Stamp and Desrochers showed that this mass can vary dramatically as vortices move, rewriting the rules of how these quantum whirlpools interact.

Michael Desrochers highlighted the importance of this realization: “It’s exciting to understand how and why the mass varies, and how this affects our understanding of quantum tunneling processes, which are ubiquitous in physics, chemistry and biology.”

The findings also loop back to Schwinger’s original idea. Stamp argues that mass variability should apply not only to vortices in helium but also to electron-positron pairs in the true Schwinger effect—meaning the analog doesn’t just mimic the cosmic process but may even refine the theory itself. As Stamp put it, this could be seen as a kind of “revenge of the analog.”

The research, published September 2 in PNAS is supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council.